Over at AEI' Enterprise Blog… Read more!

Friday, July 9, 2010

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

How Social Security’s cash flows have worsened

Monday, May 4, 2009

Retirees who work must return $250 stimulus check

Donald Lambro reports for the Washington Times that Seniors who also work and qualify for Mr. Obama's $400 Making Work Pay middle-class tax cuts may find themselves forced to give back some or all of the Social Security bonus come tax-filing time in 2010. The basic story is that Obama's making work pay tax credit – which is, in effect, a cut in the employee share of the Social Security tax – benefit only those with earned income. Retirees squealed, as you'd expect, that they hadn't gotten their share of the stimulus loot and so a $250 check was added for everyone receiving Social Security benefits. The hitch is that many people both work and receive benefits at the same time. Those folks probably expect that they'd get to keep both checks, which isn't unreasonable given that they fulfill the criteria for both. According to Lambro, that's not how it works. Congressional and IRS officials say taxpayers cannot double-dip into both programs. If you are getting extra Social Security money and benefit from a lower withholding in your paycheck, the two will have to be reconciled when you file your 2009 tax returns next year. While I'm not a huge fan of either the Making Work Pay credit or the $250 retiree checks, the administration should at least have been more forthcoming with details regarding how the program worked. According the SSA's Income of the Population Aged 55 and Over, 46% of beneficiaries aged 62-64 (1.13 million people) have earnings; 22% of beneficiaries aged 65 and older (5.4 million people) have earned income. These folks may not be too pleased come tax time.

Friday, April 3, 2009

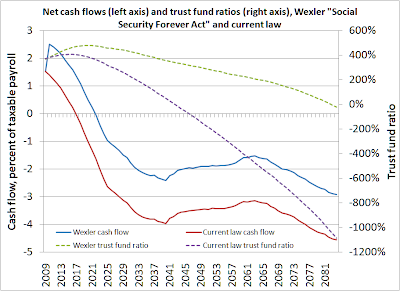

Wexler reintroduces Social Security (almost) Forever Act

Florida Rep. Robert Wexler reintroduced his "Social Security Forever Act," which would impose a 6 percent surtax on earnings above the taxable maximum of $106,800. The tax would be split evenly between employers and employees, and no additional benefits would be paid based on the extra taxes. Off the top of my head, this would increase Social Security's revenues by around 1 percent of payroll, since around 16 percent of total earnings are above the current wage ceiling and Wexler would tax 6 percent of them, which equals 0.96 percent of payroll. Using the GEMINI microsimulation model I simulated the effects of Wexler's plan on Social Security solvency. The chart below shows both the system's net cash flows and its trust fund ratio (the trust fund balance divided by that year's benefit payments), both compared to current law. Trust fund solvency is clearly what Wexler was aiming at here, as the trust fund ratio would remain positive throughout 75 years but become insolvent soon thereafter. However, this plan doesn't approach so-called "sustainable solvency" in which the trust fund would remain healthy after 75 years. Moreover, the plan depends on building new trust fund surpluses today to help finance deficits in the future, the same philosophy taken in the 1983 reforms. There's not much point in belaboring the problems with that approach. Annual cash flows, while better in every than under current law, still run pretty significant deficits beginning in around 2022, versus (we think) 2017 under current law. I'm not sure a trust fund-based approach is going to be that effective in truly prefunding future cash flow deficits, but at least Rep. Wexler has the guts to put his plan on the table – which is more than can be said about most Members of Congress, Republicans or Democrats.

Monday, December 29, 2008

Is the Social Security tax regressive once you account for benefits?

It's sometimes argued that, while income taxes are progressive, the progressivity of the total tax code has to be viewed inclusive of payroll taxes, which are either flat (in the case of the 2.9% Medicare tax) or regressive (in the case of the 12.4% Social Security tax, which applies only to the first $106,000 in earnings). It's not always clear from these statements what the net effect is. A new CBO letter allows for a better view of this, although even this doesn't tell the whole story (as I'll discuss below). The picture below first shows effective income tax rates by income quintile, for people in 2005. As you'd expect, they're pretty progressive, and the poorest 40 percent of Americans pay negative rates through policies like the Earned Income Tax Credit. The next picture shows effective social insurance – Social Security and Medicare – tax rates, also by income quintile. While rates are somewhat progressive through the fourth quintile, they decline for the top quintile because of the cap on Social Security taxes. If we add social insurance and income taxes, along with corporate income and excise taxes, the next picture shows total effective federal tax rates. As you can see, even if we add social insurance taxes, the overall tax code is still reasonably progressive (in my view; others may defined reasonable differently). But below is a chart I've constructed from a different data source, the GEMINI model of Social Security financing. The key issue with Social Security taxes is that while the tax itself is regressive, the benefits are progressive. Since taxes pay for benefits, you want to look at the progressivity of the Social Security program as a whole. The chart below is for individuals retiring in the 2030s, although they would not be much different for people retiring earlier or later (it's just the data I had lying around…). I've calculated effective payroll tax rates by lifetime earnings quintile, which means the payroll tax paid minus the disability and retirement benefits the individual receives. If you received benefits exactly equal to your taxes (plus interest at the government bond rate) then your net tax would be zero. Although net tax rates are always lower than the statutory 12.4% rate, at least for people (as here) who survive to retirement, the distributional picture is very different. The highest quintile of lifetime earners pays a net tax of around 3 of earnings. This implies that they pay 12.4% of wages while working, but then receive benefits back equal to around 9.4% of wages. While this isn't a great deal – in a fully funded system they'd receive back everything they paid in – it's better than paying 12.4% and getting nothing back. But notice what happens as lifetime earnings decline. Net tax rates are negative, meaning that (under current law benefits, at least) most folks would get out more in benefits than they pay in taxes. For the lowest earners, net taxes are very negative, around -27 percent. This means that on average these folks receive about three times more in benefits than they pay in taxes. Remember this the next time someone says that the Social Security tax is regressive: sure, it is, but things look very different when benefits are counted into the picture. As a P.S., why are net tax rates more negative for the middle quintile than for the second quintile? The answer to that is, I don't know – although because this data output mixes both retirement and disability benefits, it should be possible to disaggregate them and get a better feel for things.