Courtesy of the always-interesting Carpe Diem: Read more!

Friday, February 27, 2009

Judd Gregg locks in on Social Security reform

The Washington Examiner reports on New Hampshire Sen. Judd Gregg, who recently withdrew as President Obama's nominee to be Commerce Secretary. Gregg is a long time crusader for Social Security and budget reforms, and he hasn't given up yet: The Republican from New Hampshire is pushing the administration for reform, an issue that many thought would have been part of his role in the cabinet had he gone forward with his nomination as commerce secretary. Click here to read the whole article.

Washington Post chides Obama on Social Security

In an editorial today on President Obama's first budget, the Washington Post said: Long-term fiscal stability will require more than getting rising health-care costs under control, as important as that is. Mr. Obama's statement Tuesday that the country should "begin a conversation" about Social Security was disappointingly anemic. The conversation has been going on for a long time. It is action that has been, and remains, missing. Click here to read the who piece.

Blahous: Social Security Fix Demands Honest Numbers

The Hudson Institute's Chuck Blahous has a new op-ed out through Bloomberg News on the lessons of the 1983 Social Security reforms: If we want the success of 1983, then we need to look at the problem with the clear eyes of 1983. That means acknowledging the size and immediacy of the coming shortfalls and rejecting accounting practices that obscure them. As the 1983 effort's unique success -- and near-failure -- shows, this level of clarity is our only hope. Click here to read the whole article.

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Huff Post: Obama Angers GOP By Brushing Over Social Security

The Huffington Post reports that GOP leaders are miffed that President Obama's budget speech seemingly backed off from a task force on Social Security reform and movement toward a bipartisan solution: After hoping that Obama might be open to some sort of bipartisan reform that would reduce benefits and raise the eligibility age -- and perhaps plant the seeds for private accounts -- Republicans are now less hopeful that he'll come their way. "I was not happy," Republican Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky told the Huffington Post. "That was the one area of his speech I was not happy with. He appears to be backing away from what I thought was an earlier commitment to tackling Social Security reform." If Obama truly has put Social Security on the back burner, I think he is missing an opportunity. Republicans want to fix this program and are willing to accept significant compromises to do so. They may not be so willing in the future. Reportedly Obama backed off due to pressure from liberal interest groups and Democrats on Capital Hill. That doesn't bode well for his ability to stand up to the much stronger forces that will inevitably fight any attempts at entitlement reform.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Alicia Munnell: A bright light in a dismal landscape

Boston College's Alicia Munnell writes in the Boston Globe about Social Security's role in the time of economic and financial crisis: Amid all the economic calamity, the Social Security program is functioning perfectly, meeting the crucial economic needs for millions of Americans. When older workers are losing their jobs and their 401(k) accounts are down about 30 percent, the ability to claim Social Security benefits serves as a backstop against severe economic hardship. Therefore, policymakers should tread carefully. Click here to read the whole article.

Monday, February 23, 2009

Friday, February 20, 2009

New paper: The 1983 Social Security Reforms: Real and Misremembered Lessons for Today's Leaders

Former White House Social Security guru and current Hudson Institute senior fellow Chuck Blahous has a new paper on the lessons that should be learned from the 1983 Social Security reforms, and some lessons that were learned that probably shouldn't have been. Here's the abstract: The 1983 Social Security amendments are today often invoked as a process model for conducting politically difficult entitlement reforms. Success in reforming entitlements now depends not only on whether negotiators can summon a similar bipartisan spirit, but also on whether they are willing to define the problem as transparently as negotiators did in 1983, and on whether they avoid analytical shortcomings that have set back subsequent reform efforts. Social Security reform will always require difficult compromises between individuals with strongly-held opposing views. Today, negotiators face a daunting additional barrier: fierce disputes about the nature, size and immediacy of the problem to be solved. There is today a significant danger of misremembering and misapplying the lessons of 1983. The 1983 effort succeeded in large part because participants from across the political spectrum had a shared understanding of Social Security's financing shortfall. Analytical methods were employed that prevented issues such as Trust Fund accounting from injecting confusion and discord into the discussion. Ironically, the 1983 amendments themselves, and subsequent accounting changes, have inadvertently destroyed this shared understanding, giving rise to pervasive misimpressions about Social Security's current finances – and about the intended effects of the 1983 reforms themselves. Specifically, negotiators in 1983 did not intend to run decades of surpluses to amass a large Social Security Trust Fund, nor would they have believed that doing so would effectively pre-fund benefits in deficit years now projected for 2017 and beyond. Click here to read the whole paper.

New paper: What does it cost to guarantee returns?

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College released a new issue brief, "What does it cost to guarantee returns?" by Alicia Munnell, Alex Golub-Sass, Richard Kopcke and Anthony Well, which analyzes the cost of protecting investors against market downturns such as the one recently experienced. This is an area I've had a great deal of interest in, so here's the introduction followed by some comments: The financial crisis has dramatically demonstrated how a collapse in equity prices can decimate retirement accounts. The crisis highlights the fragility of existing 401(k) plans as the only supplement to Social Security and has sparked proposals to reform the retirement income system. One component of such a system could be a new tier of retirement accounts. Given the declines in the share of earnings Social Security will replace, these accounts would bolster replacement rates for low-wage workers and increase the security of middle- and upper-wage workers who increasingly rely on their 401(k) plans to supplement Social Security. However, these new accounts could face the same risk of collapse in value seen over the past year in 401(k)s. So policymakers may find some form of guaranteed return or risk sharing desirable to prevent huge variations in outcomes. This brief explores the feasible range and the cost of the first option – guarantees... The paper makes a solid presentation of issues regarding guarantees against market risk, and a clear distinction between the fact that while such guarantees would have been cheap retrospectively, meaning that market returns have been sufficiently high that the guarantees would rarely have needed to be accessed, prospectively such guarantees would be very expensive to provide via financial markets. Guarantees are in essence put options, which allow you to sell your portfolio for a guaranteed minimum price even if the market price of that portfolio has fallen. Put options can easily be priced using the Black-Scholes formula, and indicate that market risk guarantees can be quite expensive. So far, so good – I agree with everything in the paper. However, I'm a little wary of the discussion of the possibility that the government could provide such guarantees more cheaply than markets could, especially since analysts on both the left and the right have proposed such guarantees without, in my opinion, fully grappling with their costs. (For instance, the pension reform proposal from Teresa Ghilarducci would guarantee investors a 3 percent real return, while the Social Security proposal from Peter Ferrara would guarantee that personal accounts would be sufficient to fund current law scheduled benefits.) In both cases, there's an implicit assumption that government can provide guarantees more cheaply than the market can, yet no strong argument why this is the case. The CRR issue brief argues that the government might be less risk averse than private markets, because it can borrow at riskless interest rates and can spread risk across generations, and therefore would "charge" a lower rate for such guarantees. But here's how the Congressional Budget Office analyzed these issues: The first argument--that the government can borrow at a risk-free rate--ignores the role of stakeholders in enhancing the government's credit quality. The Treasury can borrow at a relatively low rate (by creating nominally safe securities) in part because of its sovereign power to tax. However, the authority to draw on the resources of others to ensure repayment of debt obligations does not reduce the risk that the government assumes by extending risky loans and guarantees. Rather, it is the means by which such risk is shifted to taxpayers and beneficiaries of government programs, who are, in essence, equity holders in the government's financial activities. For example, suppose the government borrows $1,000 through the sale of Treasury securities and makes a risky loan for $1,000. In balance-sheet terms, the government has acquired a risky asset that will pay $1,000 at most and a risk-free liability of $1,000. That transaction adversely affects stakeholders because they now bear more financial risk than before the loan was made: they are liable for repayment of the government securities, independent of the performance of the loan. If the loan returns only $900, stakeholders lose $100. In fact, financing a loan with a debt issue implies that stakeholders have the equivalent of a highly leveraged, and hence very risky, ownership position in the loan. The critical implication of that example is that the government's ability to create a risk-free liability results from its sovereign authority to draw on the people's resources. That authority does not protect stakeholders from market risk, nor does it increase the value of a loan above its market value. The second argument--that the cost of risk is lower to the government because it can spread the risk more widely--is relevant to diversifiable risk but not to market risk. It is sometimes argued that the government can spread losses more widely over the population than, say, insurance companies can by compelling participation in the risk pool. However, as noted above, market risk cannot be eliminated by diversification because it results from an aggregate change in asset values. Even if the government eliminated the diversifiable risk inherent in its lending activities, the associated market risk would remain. At best, a government guarantee could shift the market risk from one group (lenders) to another (taxpayers and other government stakeholders). A related argument is that the government's ability to borrow and repay that borrowing with future taxes allows it to reduce market risk by spreading the risk among generations. However, borrowing does not increase total resources; rather, it redistributes existing resources from lenders to borrowers. Moreover, risk is not reduced by the government's power to print money, because financing credit losses by creating money substitutes an inflation tax for a pecuniary tax. In the end, someone must bear the consequences of unpredictable financial returns, and markets determine a price for assuming that risk. The short story is that the government isn't an entity unto itself, such that it can bear risk or have a risk aversion significantly different from that of the population that participates in markets. Rather, the government transfers risk from some stakeholders to others; a guarantee against risk for some people is exposure to risk to others. In a paper on pricing Social Security personal account guarantees with Kent Smetters of Wharton and Clark Burdick of SSA, we summarized the research in this way: The consensus in the academic literature is that it is unlikely that the government has much, if any, advantage in risk sharing relative to the private market. Moreover, even if the government did have an advantage, especially between generations, it is not obvious that the optimal direction of risk shifting is from older retirees to younger workers, as implicit in a benefit guarantee. As a result, policymakers arguably should not treat risk much differently than individual investors who consider both expected outcomes and risk. We include some additional discussion of these government vs. market issues that may be of interest. The point here isn't to beat up on the CRR paper, which is timely, useful and well written. However, given the direction of policy proposals from both left and right and the government's general inability to price risk in any context (see this AEI forum for copious examples), I wanted to discuss this issue in depth.

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Event: Financial Literacy in Times of Turmoil and Retirement Insecurity Friday, March 20, 2009

Financial Literacy in Times of Turmoil and Retirement Insecurity Friday, March 20, 2009, 8:50 am – 4:30 pm The Brookings Institution, Falk Auditorium, 1775 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC The financial crisis has caused a reported $2 trillion loss in retirement accounts nationwide. A majority of Americans are worried their retirement funds may not be sufficient, and young and old alike are concerned about financial and retirement security. On March 20, the Brookings Institution, Wharton's Pension Research Council and Boettner Center, the University of Michigan Retirement Research Center, and The Retirement Security Project will co-sponsor a conference on financial literacy and retirement preparedness. The conference will focus on how workers and retirees can better manage saving for retirement, and how they can stay secure during retirement. Participants will identify research and policy directions for the future. After their presentations, speakers and panelists will take questions from the audience. Lunch will be provided. 8:50 Welcome Jason Fichtner Social Security Administration 9:00 Financial Literacy, Planning and Retirement Saving Annamaria Lusardi Dartmouth College Olivia Mitchell The Wharton School Julie Agnew College of William and Mary Robert Willis University of Michigan 10:30 Financial Illiteracy and Retirement Expectations: Prospects for Longevity, Decumulation and Health Michael Hurd RAND Corporation Erzo F.P. Luttmer Harvard Kennedy School Nick Maynard D2D Fund 11:45 Keynote Address The Honorable Michael Astrue Social Security Administration 12:15 Lunch and Roundtable Discussion of Agency Initiatives Debra Golding US Department of Labor Jeanne Hogarth Federal Reserve Board John Gannon Financial Industry Regulatory Authority Kristi Kaepplein Securities and Exchange Commission Dubis Correal US Department of the Treasury 1:45 Alternate Approaches to Financial Literacy Shawn Cole Harvard Business School David C. John The Retirement Security Project and The Heritage Foundation J. Mark Iwry The Retirement Security Project and The Brookings Institution Brigitte Madrian Harvard Kennedy School 3:00 Marching Orders for Research and Policy William Gale The Retirement Security Project and The Brookings Institution Angela Hung RAND Corporation Sheryl Garrett Garrett Planning Network Mike Staten University of Arizona and Take Charge America 4:15 Closing Remarks John Laitner University of Michigan To RSVP, please call the Brookings Office of Communications at 202.797.6105, or visit http://guest.cvent.com/i.aspx?4W,M3,49672225-5561-46cd-b5cd-d213a7660c25 For questions, please contact, Jaime Matthews at 202.741.6524 or jmatthews@brookings.edu.

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Vox EU: Have social security reforms shifted too much risk to individuals?

Monika Bütler at Vox EU writes, "Have social security reforms shifted too much risk to individuals? The financial crisis suggests they might have." Here's the basics, but read the whole piece, which is good. Pension system reforms have increased individual choice and individual risk. This column says that the current crisis proves that those reforms exposed individuals to too much risk. It argues for greater use of intergenerational transfers and says that it would be better if retirement plans were treated as insurance rather than pure investment decisions. Here's one problem I see with the argument, although there are others: on the one hand, folks argue that Social Security is so important because so many retirees are so dependent on it. On the other hand, they also argue that retirees are exposed to too much risk. Unless "too much" means "any" then I think this is overstated. We'd like workers and retirees to have a diversified portfolio of investments and income sources. Strengthening and, in some important cases, reforming individuals saving makes sense, as does strengthening and reforming government pension provision. But I don't see even our current situation as a "case closed" type argument regarding individual pension saving.

Event: Real Change or Pocket Change? The High Stakes of Entitlement Reform for Young Americans (February 18, Washington, DC)

The Heritage Foundation will host an event tomorrow, Wednesday February 18, entitled "Real Change or Pocket Change? The High Stakes of Entitlement Reform for Young Americans." Here's the info; click here to register: Date: February 18, 2009 Time:12:00 noon Speaker(s): Featuring Keynote Remarks by: Followed by Commentaries from: Diane Lim Rogers Alexander Hertel-Fernandez Ryan Lynch Host(s): The Heritage Foundation Details: Location: The Heritage Foundation's Lehrman Auditorium Discussions of stimulus plans and government bailouts dominate the current political debate, but our most daunting fiscal challenge is the soaring cost associated with Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The unfunded obligations for these and other federal programs already impose a $175,000 debt burden on all Americans, which is seventy-five times greater than the recent federal bailout. This debt grows every year, posing an even greater challenge to the health and vigor of the economy that young Americans stand to inherit. For these reasons, it is critical that young Americans engage on this issue. Join us for an intergenerational and bipartisan dialogue about America's fiscal climate and policy options for entitlement reform.

Andrew Yarrow

Vice President and Director,

Washington DC Office,

Public Agenda

Stuart Butler

Vice President,

Domestic and Economic Policy Studies,

The Heritage Foundation

Chief Economist,

The Concord Coalition

Senior Fellow,

Roosevelt Institute,

and Social Insurance Research Assistant,

Economic Policy Institute

National Director,

Students for Saving Social Security

Monday, February 16, 2009

Marc Goldwein: The end of the ownership society?

The New America Foundation's Marc Goldwein has an excellent article in George Mason University's History News Network on the influences, rise and potential decline of what President Bush called the "ownership society," embodied by the idea of personal accounts for Social Security. It's a very good piece and well worth reading. For what it's worth, here's an old article of mine which argues for the non-financial benefits of ownership. I still think the basic rationale for ownership has merit and many of the arguments against it don't stand up to scrutiny. But Goldwein's article is more about the political dynamics, and there I agree that with the decline in the stock market, housing prices, etc., the idea of personal ownership has taken a knock.

Sunday, February 15, 2009

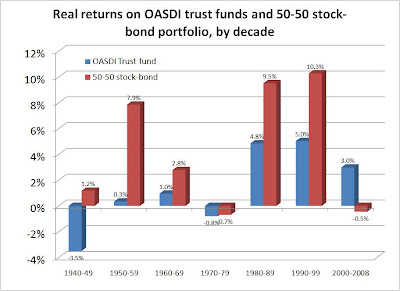

The Social Security trust fund is a safe, dependable return. Right?

With the stock market crash, many have pointed to the safety and security of Social Security relative to 401(k) plans and the idea of adding personal accounts to Social Security. There is certainly merit to these arguments, and having a diversified portfolio of safe and risky investments makes sense. At the same time, it's worth checking into how Social Security's investments have done over time. Surplus taxes paid into Social Security are invested in the Old Age, Survivors and Disability Trust Funds (OASDI), which hold special-issue government bonds whose interest rates are based on average Treasury bond interest rates at the time. The idea here is investments which provide safe, if modest, returns for the long-term. But not many people have considered how modest. Effective annual interest rates on the trust funds are available through the Social Security actuaries' web site (see here). To calculate real returns I subtracted the annual rate of growth of the consumer price index (CPI), available here. A couple charts tell an interesting story. First is a fairly conventional comparison: how did the trust funds' returns compare to a mixed portfolio of 50 percent stocks and 50 percent bonds? The first chart shows average annual returns by decade and shows a couple interesting things. First, the mixed portfolio returns exceeded the trust fund's returns in all decades except for the truncated 2000-2008 period, by an average of around 2.9 percent. Second, both the stock-bond portfolio and the trust funds lost money in two decades, although only the trust funds had a truly terrible decade, losing 3.5 percent annually during the 1940s. The second chart shows a running average return on the trust funds, beginning in 1940. The return value for each year represents the average of returns from 1940 through that years. Here's something I found pretty interesting: from the program's inception through 1986, the average annual return on the trust funds was negative. To repeat, through the first four and one half decades, the trust fund's investments lost money on average each year. Following 1986 the running average of annual returns was positive, but barely so: even extending through 2008, the average annual return on trust fund investments, adjusted for inflation, was only 1.38 percent above inflation. These returns are safe, to be sure, but far lower than the 4.4 percent real annual return on the stock-bond portfolio. So here's a question: if the trust fund's returns have been so low, how did Social Security manage to pay such high benefit returns to early retirees? (The benefit return is a function of taxes paid and benefits received, with the trust fund's investment return having an only indirect effect on benefits.) We've talked here several times about the high returns paid to early retirees; here's a chart showing average annual returns paid to beneficiaries. The answer is that while a sustainable Social Security program would have built up a significant trust fund balance over time to help pay future benefits, the trust fund balance was kept very low and the extra funds paid out as benefits. When Social Security was begun, the idea was for it to become a "funded program" carrying a large trust fund balance. Congress soon acted to delay scheduled tax increases and move up the payment of benefits, in addition to making benefits more generous. (Lesson: past Congresses were pretty much like present ones in terms of catering to current voters over future ones.) High benefits were paid, at the expense of the trust fund balance that could help the system fund itself in perpetuity. This was, in effect, like eating your seed corn: things look good in the short-term, but you don't have the means necessary to keep things going for the long run.

LA Times: Social Security isn't broken; don't 'fix' it

Michael Hiltzik writes for the LA Times that They say that even the worst tragedies harbor the seed of something good. So here's something positive in the stock market's gruesome behavior over the last year: It may finally have driven a stake through the heart of the campaign to "fix" Social Security. You get the feeling where this is going. My wife just gave birth so I'm a bit sleep deprived, but if I can be motivated I'll dissect this one later.

Let's be plain about one thing: This campaign, cooked up mostly by Wall Street investment houses and conservative Republicans, was always about "fixing" Social Security the way one "fixes" a cat.

Sen. Bennett reintroduces Social Security reform plan

The Deseret News "We are literally facing a retirement tsunami with the number of retirees projected to increase by 75 percent between 2010 and 2030. This legislation would ensure that our children and grandchildren will receive roughly the same level of benefits when they retire as current retirees do today, and we can do this without raising taxes." The Bennett plan has three parts: Together, these steps could be expected to keep the program solvent over the long term. Here's a link to the SSA actuaries' analysis of the 2006 version of Bennett's plan.

reports that Sen. Bob Bennett (R-UT) has reintroduced his plan to reform Social Security. Bennett said:

SSA faces challenge in Baby Boom retirements

While most press attention, and my own focus, is on how Baby Boomer retirements will affect Social Security's large-scale financing, handing the retirement and disability applications of 10,000 Boomers per days is a huge administrative challenge for the Social Security Administration. This is particularly so given that SSA itself faces a wave of retirements within its own staff. The Washington Post

reports on a new GAO study on the administrative challenges faced by the SSA. While the Baby Boomers began retiring last year, they are already in their peak years for disability insurance applications, which are significantly more difficult to process than retirement applications. From my own experience, while productivity can be improved at any large organization, particularly in government, the staff at SSA have increased output considerably and Commissioner Astrue has been proactive in looking at a variety of ways to streamline applications processes. It's beyond me to judge what the appropriate level of staffing and resources is, particularly given the ability to substitute technology for manpower these days, but it seems clear the agency will be hard pressed in coming years and Congress should pay close attention to SSA's needs.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Politico: Left silent on Social Security, Medicare (for now…)

The Politico reports on the Democratic base's response to President Obama's renewed willingness to take on the challenge of rising entitlement spending. Obama appears to be getting unusual room to maneuver on entitlements by most of his liberal allies. On the subject of entitlement reform, in fact, Obama's honeymoon continues — at least in the unlikely precincts of the Democratic left, a counterintuitive development that has buoyed the spirits of reformers who would like to see drastic changes in the way Social Security works. But have no fear: should President Obama yield to the mathematical necessity of "cutting" – meaning, reducing the growth of – Social Security and Medicare, "'he's going to hit a wall real fast,' said Dean Baker, co-director of the left-leaning Center for Economic and Policy Research." This will be a major leadership challenge for Obama. If he wishes to truly be a change agent, entitlement reform will put his talents to the test.

Opponents of significant changes to Social Security benefits were jarred in January, when the then-president-elect echoed George W. Bush's claim of an entitlement "crisis," warning of "red ink as far as the eye can see" in Social Security and Medicare. Obama promised that those programs would be a "central part" of his plan to reduce the federal deficit.

Social Security defenders were surprised again last week, when Obama named a leading voice for reining in entitlement spending, New Hampshire Sen. Judd Gregg, to his Cabinet.

But despite some grumbling in the ranks, the powerful, organized movement that effectively defended the Social Security status quo from Bush's ambitious reform effort in 2005 has been one of the key dogs that haven't yet barked at Obama.

Michigan RRC newsletter and key findings of new research

The University of Michigan Retirement Research Center, part of the larger retirement research consortium funded by the Social Security Administration, has released its winter newsletter. You can read the whole thing in PDF by clicking here. I've pasted below a section of the newsletter highlighting key findings from recent MRRC working papers. The full papers are available at the MRRC website. How Much Do Respondents in the HRS Know About Their Tax-deferred Contribution Plans? A Cross-cohort Comparison by Irena Dushi and Marjorie Honig WP 2008-201 Does The Optimal Design of Social Security Benefits by Shinichi Nishiyama and Kent Smetters WP 2008-197 The Labor Supply Effects of Disability Insurance Work Disincentives by Nicole Maestas and Na Yin WP 2008-194 Labor Market and Immigration Behavior of Middle-Aged and Elderly Mexicans by Emma Aguila and Julie Zissimopoulos WP 2008-192

the Rise in the Full Retirement Age Encourage Disability Benefits Applications? Evidence from the HRS by Xiaoyan Li and Nicole Maestas WP 2008-198

New publication: Income of the Population 55 or Older, 2006

The Social Security Administration's Office of Retirement and Disability Policy has released the latest update to its long-running series, "Income of the Population 55 or Older." This is a very useful collecting of data on retirees and near-retirees. Click here to access it.

Friday, February 6, 2009

New Social Security papers from NASI

The National Academy of Social Insurance has released a series of research papers on the need to improve Social Security benefits for low earners. Here's their press release, followed by links to the papers. I was part of this research project and appreciate the support of NASI and the Rockefeller Foundation for this work, as I'm sure my fellow authors do as well. PRESS RELEASE: Economic Crisis Underscores Need to Improve Social Security Benefits

NASI Report Features 12 New Ideas

Project is Part of Rockefeller Foundation's Campaign for American Workers

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 20, 2009

CONTACT: Virginia Reno (202-452-8097 or vreno@nasi.org) or Bob Zachariasiewicz (240-888-3476)

WASHINGTON, DC – The financial crisis has exposed the profound vulnerability of rank and file Americans to the risks of a market economy and points to the need to address the adequacy of Social Security benefits. The National Academy of Social Insurance (NASI) today issued 12 policy proposals in a new report, Strengthening Social Security for Vulnerable Groups.

"Declining home values, shrinking retirement accounts, and rising joblessness imperil dreams of a secure retirement for seniors and working families. Social Security is the source of retirement income that remains secure despite the market meltdown," noted Kenneth Apfel, Chair of the NASI Board of Directors.

Independent scholars, who were selected by an expert NASI committee, developed the new policy ideas with support from the Rockefeller Foundation. "These new ideas are timely as President Obama and the 111th Congress consider how to help families deal with losses in their other retirement funds," said Judith Rodin, the Foundation president. "The Rockefeller Foundation is proud to support NASI's pioneering approach to rethinking the social contract of the 21st century, and in particular its application to poor and vulnerable people."

The policy ideas, which reflect the views of the independent scholars, aim to improve Social Security protections for low-wage workers, elderly widows, the oldest old, disabled individuals, farm workers, and low-paid workers with careers interrupted by caring for children or aging family members. The proposals and scholars are listed on page 2 of the report.

The National Academy of Social Insurance is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization made up of the nation's leading experts on social insurance. Its mission is to promote understanding of how social insurance contributes to economic security and a vibrant economy.

Policy Proposals and Scholars:

Safer than the Mattress: A policy to ensure that Social Security and other exempt federal benefits remain safe from garnishment, attachment, and freezes when deposited in a bank account, by John Infranca, Federal Judiciary, Philadelphia, PA

Improving Social Security Disability Programs for Adults Experiencing Long-Term Homelessness, by Yvonne Perret, Advocacy and Training Center, Cumberland, MD, and Deborah Dennis, Policy Research Associates, Inc., Delmar NY

Strengthening Social Security for Farm Workers: The Fragile Retirement Prospects for Hispanic Farm Worker Families, by Barbara Robles, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ

The Effects of Reducing Eligibility Requirements for Social Security Retirement Benefits, by Andrew Biggs, American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, DC

Strengthening Social Security Benefits for Widow(er)s: The 75 Percent Combined Worker Benefit Alternative, by Joan Entmacher, National Women's Law Center, Washington, DC

Enhancing Social Security for Low-Income Workers: Coordinating an Enhanced Minimum Benefit with Social Safety Net Provisions for Seniors, by Laura Sullivan, Tatjana Meschede, and Thomas M. Shapiro, Institute on Assets and Social Policy, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA

A New Minimum Benefit for Low Lifetime Earners, by Melissa Favreault, The Urban Institute, Washington, DC

Crediting Care in Social Security: A Proposal for an Income Tested Care Credit, by Pamela Herd, La Follette School of Public Affairs, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI

Retirement Security for Family Elder Caregivers with Labor Force Employment, by Shelley White-Means, University of Tennessee, and Rose Rubin, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN

Restoring Old Age Income Security for Low-Wage Single Workers, by Patricia E. Dilley, University of Florida Levin College of Law, Gainesville, FL

Longevity Insurance: Strengthening Social Security for the Old-Old, by John Turner, Pension Policy Consultant, Washington, DC

Strengthening Social Security for Workers in Physically Demanding Occupations, by Eric Klieber, Buck Consultants, Cleveland, OH

New paper: The effects of reducing eligibility requirements for Social Security retirement benefits

I have a new paper released through the National Academy of Social Insurance titled "Effects of reducing eligibility requirements for Social Security retirement benefits." It was supported and released as part of NASI's project on enhancing Social Security benefits for low earners, a project supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. Here's the executive summary: Under current law, eligibility for Social Security retirement benefits requires 40 quarters (roughly 10 years) of earnings in covered employment. While individuals with less than 40 quarters of employment may receive benefits based on the earnings record of an eligible spouse, a small number of unmarried individuals fail to qualify for retirement benefits due to a short earnings record. These non-qualified individuals often must depend on Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for support in retirement. However, SSI eligibility requirements limit earnings and asset accumulation, making it more difficult for beneficiaries to work or save. This paper explores the effects of eliminating the 40 quarters eligibility requirement. Doing so would allow retirement benefit eligibility for individuals with very short work histories and reduce dependency on SSI benefits. The effects of reducing the 40 quarters eligibility requirement are analyzed for the 1950 birth cohort using the Policy Simulation Group's GEMINI and PENSIM microsimulation models of the Social Security population and private pensions. Eliminating the 40 quarters eligibility requirement would increase benefits for approximately 5.8 percent of individuals. These benefit increases would be concentrated in the bottom three deciles of lifetime earnings, where 15 percent of individuals would receive increased benefits. Average benefit increases for affected individuals in the bottom three deciles of earnings would be around $2,400 per year. Benefit increases are concentrated among immigrants, whose shorter periods in the labor force increase the likelihood of not satisfying the current 40 quarters eligibility requirement. Due to the relatively small number of affected individuals, increases in total system costs would be modest. The 75-year actuarial deficit would increase from 1.70 percent of taxable payroll under current law to around 1.79 percent of payroll. While reducing or eliminating the 40 quarters eligibility requirement could increase benefit availability for very low lifetime earners, it would also increase benefits for individuals whose primary earnings were derived from employment not covered by Social Security. These individuals, mostly employees of state and local governments, could receive windfalls if other corrective actions were not taken. However, application of the existing WEP/GPO provisions to newly Social Security eligible state/local government employees could help correct for any imbalances in relative benefit generosity, although some modifications to WEP/GPO rules to maintain neutrality between covered and non-covered employees may be necessary. Moreover, increased Social Security retirement benefits could potentially remove individuals from SSI, which could then put at risk these individuals' eligibility for means-tested assistance programs such as Medicaid and Food Stamps. In most cases, however, increased Social Security benefits would supplement SSI rather than eliminate it.

Soliciting papers for fall APPAM conference

Dear colleague, Have you considered participating in the fall 2009 Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management (APPAM) conference to be held in Washington D.C. on Nov 5-7? Proposals for papers or sessions are due on Tuesday, March 10 and must be submitted online. APPAM is keen on papers in the field of aging, among other topics. APPAM organizers have posed the following challenge: "As President Obama's administration begins to implement change, what evidence can APPAM members bring to the debate on failed policies in need of change, on successful policies in need of retention or expansion, and on the parameters that will allow us to tell the difference?" To submit a proposal, please visit http://www.appam.org/conferences/fall/dc2009/call.asp Thanks, Joyce Manchester, Congressional Budget Office Andrew Biggs, American Enterprise Institute

Thursday, February 5, 2009

Social Security Statement to Include Savings Leaflet for Younger Workers

For years the Social Security Administration has included a leaflet on preparing to retire with the annual Social Security benefit statements sent to older workers. A project that began while I was at Social Security is to produce a separate insert geared toward the needs of younger workers. That project is now underway: Beginning in February 2009, workers age 25-35 who receive a Social Security Statement also will get an insert called What young workers should know about Social Security and saving. This new supplement provides additional information that pertains to young workers and includes a chart showing how much difference a little bit of saving can make. For all workers 25 and older not yet receiving benefits, the Statement includes a person's estimated benefit for different retirement ages, and for disability and survivors benefits, as well as a person's annual earnings and amount paid into Social Security. In 2000, Social Security began including an insert with the Statement for all workers age 55 and older who were not receiving benefits. The agency recently revised the supplement, called Thinking of Retiring?, to add more information, make it more appealing visually and include a chart to show how much benefits can be worth at different ages. I'm very happy that this is now up and running. I know from experience that putting the younger workers insert together was a lot of work. My congrats to the SSA staff who put the material together and to Commissioner Mike Astrue and Deputy Commissioner Jason Fichtner for being so pro-active. Basic retirement savings information can now be provided to every American. Given the state of financial literacy in this country, that's a very positive step.

Elliot Spitzer whiffs on Social Security reform

There is one statement in Elliot Spitzer's Slate.com article on Social Security personal accounts that I fully agree with: "'We told you so' is just about the most annoying sentence one can utter." Sure is. Beyond that, though, Spitzer's argument that stock market declines over the past year just prove the foolishness of individual investing is pretty flaccid stuff. Spitzer begins by simply highlighting that "Since Jan. 1, 2005, the year President Bush proposed the idea, the Dow Jones industrial average has dropped from 10,783 to around 8,000, a drop of more than 25 percent." Ok, but in the Bush plan older workers accounts would automatically switch to bonds beginning at age 55, meaning that most people retiring today would have had much less exposure to that falling market than younger workers. Then Spitzer says that he will quantify the losses to today's retirees, "abeit roughly." Spitzer should have said albeit very roughly, since Spitzer relies for his numbers on a Fortune article by Allan Sloan that Sloan himself later retracted due to technical misunderstandings of how personal account plans would have worked. In this recent post, I gave the results of a much more detailed simulation of personal accounts using historical market returns. The short story is that there is no historical period in which a worker holding an account for a full career would have failed to significantly increase his total Social Security benefits, including workers retiring today. Moreover, even workers who held an account for only a few years before retiring under today's market conditions would have experienced only tiny declines in total Social Security benefits. Finally, Spitzer says, "as Paul Krugman has pointed out, the would-be privatizers make incredible—even impossible—assumptions about the likely performance of the market to justify their claim that private accounts would outdo the current system." The basic argument here is that as a slow-growing workforce reduces long-term GDP growth, stock returns must be lower as well. But here's the problem: first, it's not the "privatizers" who make assumptions regarding future stock returns, it's the non-partisan actuaries at Social Security and economists at the Congressional Budget Office. Second, as I showed in this blog post using historical data from sixteen countries over a 100-year period, the correlation between GDP growth and stock returns is statistically very weak. There are plenty of good arguments to make against adding personal accounts to Social Security. Spitzer should have spent more time actually making them.

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

Judd Gregg role on entitlement reform?

One reason Republicans regretted New Hampshire Sen. Judd Gregg's acceptance of President Obama's nomination as Commerce Secretary is that the Senate would lose one of its strongest voices for long-term budget and entitlement reforms. Gregg was a leading sponsor of the so-called Gregg-Breaux Social Security Reform Act, which was co-sponsored by Sens. John Breaux (D-LA), Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Bob Kerrey (D-NE), Chuck Robb (D-VA), Craig Thomas (R-WY) and Fred Thompson (R-TN). More recently, Gregg has teamed up with Budget Committee chairman Sen. Kent Conrad to sponsor a commission to take on long-term tax and spending challenges, including entitlement reforms. These are big shoes to fill. But it appears all is not lost. A story in Politico today contains the following note: In something of a surprise, the fiscally conservative Gregg noted that Obama selected him "especially" for his work on entitlement reform. "If our credit is going to be good and our dollar is going to be strong, we have to address entitlement reforms," the Republican said. While the Commerce Department has not before played a strong role on entitlement reform, Gregg's will be a strong voice within the administration for restraining the growth of entitlement spending and putting the nation's long-term books in order. Update: The Manchester Union Leader weighs in here.

New paper: The Forgotten Entitlements

My AEI colleagues Henry Olsen and Jon Flugstad have a new article out in Policy Review on what they call "The Forgotten Entitlements," Social Security disability insurance and Medicaid long-term care. Both programs are rising in cost and both, Olsen and Flugstad argue, are in need of structural reform. When politicians and policy wonks use the phrase "the looming entitlement crisis," most listeners know exactly what that means: Social Security and Medicare. Spending on these programs is rampant, nearly $1 trillion in fiscal 2006, and is projected to grow exponentially over the coming decades. By 2082, due to the aging of baby boomers, rises in health-care expenses, and expected lower fertility rates, Social Security and Medicare are projected to cost nearly 18 percent of gdp--roughly what the entire federal government costs today. It is now common, if as yet unacted upon, wisdom in the Beltway that if the price of these programs is not reined in, Americans will have to suffer either substantial tax increases, unsustainable budget cuts, or both. But the bad news does not end there. It turns out that Social Security and Medicare are not the only out-of-control federal entitlements. Two little known entitlement programs, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Medicaid Long Term Care (LTC), are also increasing at unsustainable rates. Call these the forgotten entitlements… To read the whole paper, click here.

Michael Kinsley on Entitlement Myths

Michael Kinsley argues in Time Magazine that we should reconsider our views of the "entitlement crisis." While always interesting, I'm not sure Kinsley's arguments really hold up to scrutiny – but see my comments below and judge for yourself. The Peter G. Peterson foundation, a new and welcome arrival on the national scold scene, announced in a December press release that the U.S. is bankrupt. Not the government but the whole country and everyone in it. As of Sept. 30, the PGP folks reported (using figures from the Federal Reserve), the value of everybody's assets was $56.5 trillion. The value of our liabilities (public and private) was $56.4 trillion. Given what has happened to real estate and the stock market since Sept. 30, it seems certain that we now owe more than we are worth. It seems certain, that is, if the PGP folks are correct. Now, I'm all for doom 'n' gloom--they've done very well for me in the journalism business over the years--but this struck me as too bad to be true. And on closer examination, it is. About $40 trillion of PGP's $56 trillion in liabilities is its calculation of future Medicare and Social Security benefits ($34 trillion of it is Medicare alone), which Congress has promised to future senior citizens but has made no provision to pay for. This is the entitlements nightmare we hear so much about. Trouble is, the PGP folks seem to have forgotten about this $40 trillion of dubious promises when totting up the assets of people who will (or possibly won't) get the benefits. If these entitlement promises are real government debts, they are also real assets for the people who will enjoy them. If (as we gloomsters suspect) they aren't real for the future recipients, then they aren't real for the government either. American families may have borrowed irresponsibly, and may have elected politicians who borrow even more irresponsibly on their behalf, but the typical American family is not bankrupt. The average couple age 65-74 has accumulated a net worth (not counting entitlement promises as either assets or liabilities) of $691,000, according to the Federal Reserve in 2004. Shortly thereafter, of course, they start to die in large numbers. And what happens to the $691,000? Generally it goes to the children and grandchildren. It's often said, on the subject of underfunded entitlements, that we are "robbing future generations." This is not completely true. You can't literally steal, say, a vacation home from the year 2050 and plant it next to a beautiful lake in 2009. Nor can you beg, borrow or steal money in 2050 and spend it in 2009. But you can reduce your savings rate in 2009, spend the money instead and leave a less prosperous country in 2050. And if you borrow money from foreigners in 2009, as we have been doing more and more, they can indeed come knocking in 2050 and demand their money back. With interest. Meanwhile, though, families--middle-class families, not just rich ones--are passing hundreds of thousands of dollars on to the next generation in their wills. Fair enough, if they worked for the money and saved it. In fact, wonderful. But much of this generosity, it turns out, is made possible by Social Security and Medicare. How much? Hard to say. What is easier to say with certainty is that most people today and in the future will get more back from these entitlement programs in retirement than they put in during their working lives. Medicare and Social Security are supposed to be insurance against the perils of old age: poverty and illness. They are not supposed to be gifts or subsidies to the children of retirees. Yet that is what, in large part, they have become. The reason for insurance is that you can't predict the future. If an elderly woman has diabetes and her husband needs heart surgery, then dies anyway, leaving her impoverished, Medicare and Social Security should be there for her. And if it all costs far more than she ever put into the system, that's O.K. too. But if our elderly woman dies with $691,000 in the bank, it's evident that she didn't need the government money to pay for her health care or to avoid plunging into poverty. She wasn't lying or cheating--she might have been legitimately worried--but her worries turned out to be unnecessary. And society, having kept its promise to her, should get at least part of that money back. Oh, yes, designing a system to achieve this would be a nightmare--maybe impossible. The incentive for old folks to squander their savings would be enormous. Maybe it can't work. But the point is worth keeping in mind as we enter President Obama's "new age" of "hard choices." And the children? Let them rob their own children, just as their parents did. Some thoughts: First, while Kinsley's point regarding the Peterson Foundation's account seems correct – a debt to someone has to be an asset to someone else – transferring massive amounts of resources through Social Security and Medicare entails significant efficiency losses. Social Security contributions are regarded as taxes by workers in ways that contributions to personal saving are not, and therefore reduce incentives to work. So while the accounting may net out, there are economic costs in getting from here to there. Second, Kinsley may exaggerate the size of inheritances that will be passed on to Baby Boomers and younger cohorts. This paper by Kotlikoff and Gokhale concludes that the bequest boom is likely overstated. Third, even if households continue to pass on significant bequests to their heirs, this won't be – as Kinsley claims – due to the generosity of Social Security. For early generations of beneficiaries, Social Security provided benefits well in excess of contributions, which – assuming seniors didn't just consume this extra income – allowed for larger inheritances. But as this memo from the SSA actuaries shows, Social Security can afford to pay a typical couple retiring in 2008 benefits and interest equal to only around 75 percent of the taxes the couple paid in over their lifetime. Social Security imposes a net tax on current and future retirees and, if anything, reduces the amount of wealth they'll have to leave to their kids.

Monday, February 2, 2009

The kind of question Social Security probably doesn’t want to answer…

A financial Q&A column in the Associated Press answers an uncomfortable question regarding Social Security spousal benefits: Q: A friend has been a stay-at-home mom while I have worked most of my adult life and raised my children. My friend and I and our husbands have recently signed up for Social Security benefits and I've discovered that my friend will get as much as I will. How, since she hasn't contributed to Social Security, can she get as much as I will? A: As the spouse of an eligible worker, your friend is entitled to half of her husband's benefit amount when she reaches full retirement age, which could be as early as 65. Her husband, at full retirement age, will receive his full benefit amount and she will get a check for half of that amount, even though she's never worked. So, your friend could feasibly be entitled to as much as you are. Your benefit amount is based on the number of years you've worked, how much you earned and the age at which you begin drawing benefits. Hers is based on half of whatever her husband's benefit is. The Social Security Administration uses a mathematical formula to figure benefits based on your average monthly earnings during the 35 years in which you earned the most. This is the amount you would receive at full retirement age, which for most people is age 65. Beginning with people born in 1938 or later, that age will gradually increase until it reaches 67 for people born in 1962 or later. The average monthly Social Security benefit for a retired worker is about $1,153 this year. In addition, your friend can get Medicare when she reaches 65. Medicare provides hospital insurance, medical insurance and prescription drug coverage. Here's how I see it: Social Security was built on the principles of equity and adequacy. Equity means that benefits are based on what you pay in, while adequacy provides a tilt to the benefit formula so low earners receive higher benefits relative to their contributions than do high earners. Neither principle justifies the payment of a benefit to the spouse of a high earner, who neither needs the money nor has paid anything into the program. Social Security benefits need to be reduced in the future in order to balance the program's books. Here's a nice place to start.

Samuelsson: Obama in a box

Newsweek's Robert Samuelson writes on the challenges of programs for the aged, both at the federal and state level, and the difficulties politicians face in addressing them: What looms is a huge transfer of income from younger workers to older retirees. Ideally, we would consciously decide how large the transfer should be. But in practice, the choice occurs semiautomatically. Social Security, Medicare and pension benefits are set by law. Unless the laws are changed, the payments go out, and the pressures on taxes and other government programs are inescapable. Beyond reassuring speeches, Obama hasn't confronted the conflicts. He's been all things to all people. Rhetorically, he's for the children. But he's also for the elderly. In the campaign, he opposed proposals for reducing the future costs of Social Security and Medicare through higher eligibility ages and lower benefits. Obama is in a box of his own making; he cannot fulfill his promises to children without repudiating some promises to the elderly. As a society, America is in the same box. The conflicts between generations may or may not incite open political warfare, but either by design or default, we will be making decisions about America's future. The old are well organized and highly protective of promised benefits, while the young are politically passionate and unfocused. For the young, the odds look lousy. Click here for the whole article.

New article “Obama vs. FDR”

I have a new article up at The American, AEI's online publication, discussing how President Obama's plans for Social Security fit within the character of the program as established by FDR. When the Social Security Act was passed in 1935, the program embodied new ideas on the role of government and engendered significant opposition. Yet one point remained clear: Social Security was not "relief," what is today termed "welfare." This new program, explained President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was to be an earned right by American workers, not a handout. This aspect of the program, the Social Security Administration (SSA) says, is "one of the basic principles of the Social Security program and is largely responsible for its widespread public acceptance and support." But some in Congress and the new Obama administration wish to make fundamental changes to how Social Security works, shifting it closer to a welfare program. The piece builds on some of my earlier article, but includes more historical material on the founding of the Social Security program. Click here to read the whole story.

Sunday, February 1, 2009

George Will : Recklessness with Social Security

Here George Will focuses on Rep. Jim Cooper, a Tennessee Democrat who has focused on long-term budget pressures: WASHINGTON -- "Recidivism" is Rep. Jim Cooper's laconic explanation of why he, although only 54, has spent portions of five decades on Congress' payroll. Responding with aphorisms (e.g., "Bad government starts at the grass roots") to the tedium of Congress' culture of avoidance, he grows more laconic as the welfare state's implosion approaches. The son of a Tennessee governor, Cooper, a Democrat who represents Nashville, was a congressional page starting in 1969 and then a Rhodes Scholar before being elected to Congress in 1982. Having run unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1994, he returned to the House in 2002. A mordant Cassandra ("If members of Congress were paid on commission to cut spending we'd see fabulous results"), he is no longer astonished by Congress' bipartisan avoidance of the predictable crisis coming to the big three entitlement programs -- Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. "Astonishing," says Cooper of the new president's avowed determination to confront the crisis. Leadership, says Cooper, who has seen precious little of it concerning entitlements, enlarges the number of "things that can be talked about." Such as the Social Security payroll tax, which Cooper would cut for several stimulative years from 12.4 percent to 8 percent. It suppresses job-creation, is raising more revenue than Social Security is dispensing and will continue to do so until 2017. The surplus is invested in Treasury bonds. That amounts to lending it to the government "which in turn," Cooper says, "spends it on everything except Social Security." President Lyndon Johnson, to make the deficit numbers during the Vietnam War less scary, adopted the "unified budget," under which Social Security's surplus was mingled with general revenues, thereby reducing -- disguising, really -- the deficit's size. That, Cooper says, was the "original sin" in the budgeting sleight-of-hand that prevents the public from knowing, and Congress from being compelled to act on, facts about the entitlement programs' unfunded liabilities -- promises to future beneficiaries that future taxpayers may not be willing to pay. Cooper, who has an unshakable appetite for unappetizing numbers, wishes more Americans were similarly eccentric and would read the 188-page 2008 Financial Report of the United States Government -- the only government document that calculates what deficit and debt numbers would be if the government practiced, as businesses must, accrual accounting. Under such accounting, future outlays to which beneficiaries are entitled by existing law are acknowledged as expenditures before they are paid. Were the Social Security surplus sequestered for accounting purposes, reflecting the truth that it is already obligated, and were there similar treatment of the other entitlement programs' liabilities, the deficit for the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30 would have been $3 trillion rather than $454.8 billion. The report's numbers show that the true national debt is $56 trillion, not the widely reported $10 trillion. The report says that in 25 years the portion of the population 65 and older will increase from 12 percent to 20 percent, while the share of the population that is working and paying taxes will decrease from 60 percent to 55 percent. If Medicare spending continues to grow, as it has for four decades, more than one and a half times as fast as the economy, the big three entitlements, which currently are 44 percent of all federal expenditures (excluding interest costs of the national debt), will be 65 percent by 2030. Under current law, 30 years from now government revenues will cover only half of anticipated expenditures. For years, many conservatives advocated a "starve the beast" approach to limiting government. They supported any tax cut, of any size, at any time, for any purpose, assuming that, deprived of revenue, government spending would stop growing. But spending continued, and government borrowing encouraged government's growth by making big government cheap: People were given $1 worth of government but were charged less than that, the balance being shifted, through debt, to future generations. In 2003, Republicans fattened the beast with the Medicare prescription drug benefit (Cooper opposed it), which added almost $8 trillion in the present value of benefits scheduled, but unfunded, over the next 75 years. Liberalism's signature achievement -- the welfare state's entitlement buffet -- will, unless radically reduced, starve government of resources needed for everything on liberalism's agenda for people not elderly. Conservatives want government limited, but not this way. Although President Obama promises entitlement reforms, what can be expected from a Congress with a long bipartisan record of reckless enrichments of the entitlement buffet? Recidivism.

David Langer must have compromising pictures of the N.Y. Times letters editor

The New York Times today published the latest of many letters from David Langer, an actuary based in New York who's made a business of sorts as a gadfly critiquing the Social Security Trustees projections of future insolvency. I really don't know how he gets so many letters published there. To the Editor: Your editorial portrays the "grim reality" facing retirees: an uncertain financial market, inadequate savings and employer contributions, shift of all risks to workers (investment, longevity) and so on. And the solutions are unsatisfactorily focused on patching up existing arrangements. Fortunately, a superb answer is available: Simply expand Social Security to provide a benefit to replace 70 percent of average pay rather than the current 41 percent. Consider: It's already set up as a national plan, does not depend on anyone's investment acumen, avoids financial chicanery, has expenses that are ridiculously low, provides longevity and cost-of-living guarantees, and has built-in job portability. And the increase in cost may be surprisingly small; it will be offset by many factors, including raising the taxable wage base, use of a large part of the current $2.4 trillion surplus, and folding in the assets of existing plans by a reasonable trade-off. Definitely worth thinking about. David Langer The writer is a consulting actuary. Ok, let's do a little back of the envelope math. The best projections of the Social Security actuaries are that to make Social Security permanently solvent would require an immediate and permanent tax increase of 3.2 percentage points – that is, an 26 percent increase in the 12.4 percent payroll tax – or an equivalent cut in benefits of around 21 percent. So, while Social Security current promises a replacement rate of 41 percent of pre-retirement earnings to an individual retiring at the full retirement age, with the taxes and resources we currently have it can actually afford to pay a replacement rate of around 32.3 percent. Langer proposes that Social Security instead pay a replacement rate of 70 percent – 2.17 times the current affordable rate. This would require that we roughly double the current payroll tax rate. Now eliminating the current $106,800 payroll tax ceiling could reduce this cost increase by around 15 percent, folding in private pension assets of around $900 billion might cut it by a percent or two, etc. But the main point is that Langer is proposing an effective doubling in size of the federal government's largest program, which is already significantly underfunded, in an environment of large present and projected deficits in the rest of the budget. People need to get a grip that we face a budget constraint and start thinking of ways to tackle it.

New York, Jan. 27, 2009