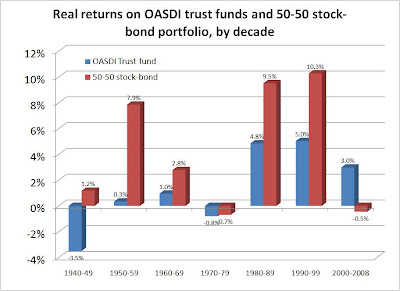

With the stock market crash, many have pointed to the safety and security of Social Security relative to 401(k) plans and the idea of adding personal accounts to Social Security. There is certainly merit to these arguments, and having a diversified portfolio of safe and risky investments makes sense. At the same time, it's worth checking into how Social Security's investments have done over time. Surplus taxes paid into Social Security are invested in the Old Age, Survivors and Disability Trust Funds (OASDI), which hold special-issue government bonds whose interest rates are based on average Treasury bond interest rates at the time. The idea here is investments which provide safe, if modest, returns for the long-term. But not many people have considered how modest. Effective annual interest rates on the trust funds are available through the Social Security actuaries' web site (see here). To calculate real returns I subtracted the annual rate of growth of the consumer price index (CPI), available here. A couple charts tell an interesting story. First is a fairly conventional comparison: how did the trust funds' returns compare to a mixed portfolio of 50 percent stocks and 50 percent bonds? The first chart shows average annual returns by decade and shows a couple interesting things. First, the mixed portfolio returns exceeded the trust fund's returns in all decades except for the truncated 2000-2008 period, by an average of around 2.9 percent. Second, both the stock-bond portfolio and the trust funds lost money in two decades, although only the trust funds had a truly terrible decade, losing 3.5 percent annually during the 1940s. The second chart shows a running average return on the trust funds, beginning in 1940. The return value for each year represents the average of returns from 1940 through that years. Here's something I found pretty interesting: from the program's inception through 1986, the average annual return on the trust funds was negative. To repeat, through the first four and one half decades, the trust fund's investments lost money on average each year. Following 1986 the running average of annual returns was positive, but barely so: even extending through 2008, the average annual return on trust fund investments, adjusted for inflation, was only 1.38 percent above inflation. These returns are safe, to be sure, but far lower than the 4.4 percent real annual return on the stock-bond portfolio. So here's a question: if the trust fund's returns have been so low, how did Social Security manage to pay such high benefit returns to early retirees? (The benefit return is a function of taxes paid and benefits received, with the trust fund's investment return having an only indirect effect on benefits.) We've talked here several times about the high returns paid to early retirees; here's a chart showing average annual returns paid to beneficiaries. The answer is that while a sustainable Social Security program would have built up a significant trust fund balance over time to help pay future benefits, the trust fund balance was kept very low and the extra funds paid out as benefits. When Social Security was begun, the idea was for it to become a "funded program" carrying a large trust fund balance. Congress soon acted to delay scheduled tax increases and move up the payment of benefits, in addition to making benefits more generous. (Lesson: past Congresses were pretty much like present ones in terms of catering to current voters over future ones.) High benefits were paid, at the expense of the trust fund balance that could help the system fund itself in perpetuity. This was, in effect, like eating your seed corn: things look good in the short-term, but you don't have the means necessary to keep things going for the long run.

Sunday, February 15, 2009

The Social Security trust fund is a safe, dependable return. Right?

Labels:

401k plans,

personal accounts,

rate of return,

risk,

Trust Fund

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

7 comments:

When you add in the fact that the "trust funds" don't really exist, the return on investment is really bad.

It is amazing that after 72 years people are just now looking at the SS Returns and how we got into this mess.

Here is a power point presentation I did years ago. I was asked to do a mini series on Social Security. We taped five shows and they aired them many times over six months. It was called "Snookered."

To access the power point presentation )converted to pdf format) go to http://www.justsayno.50mgs.com

or use the link

http://www.justsayno.50megs.com/ss.html

If you copy this link http://www.justsayno.50megs.com/pdf/social_security.pdf to your address bar you can also down load it. If you try to access it from inside a another web site, you may not be able to.

A. J. Altmeyer, Chairman

Social Security Board Before the House Ways and Means Committee November 27, 1944

“There is no question that the benefits promised under the present Federal old-age and survivors insurance system will cost far more than the 2 percent of payrolls now being collected. As I pointed out in my testimony of last year, none of the actuarial estimates which have been made on the basis of present economic conditions and other factors now clearly discernible result in a level annual cost of this insurance system of less than 4 percent of payroll.”

“Indeed, under certain assumptions the level annual cost has been estimated to be as much as 7 percent of payrolls. On the basis of a 4-percent-level annual cost it may be said that the reserve fund of this system already has a deficit of $6,600 million. On the basis of 7-percent-level annual cost it may be said that the reserve fund already has a deficit of about $16,500 million.”

http://www.ssa.gov/history/aja1144a.html

Robert Ball

Commissioner of Social Security

1962 and 1973,Wrote June 2005

“When Social Security began, benefits for those nearing retirement age were much higher than could have been paid for by the contributions of those workers and their employers. This was done so that the program could begin paying meaningful benefits even though workers nearing retirement would have only a short time to contribute.” “Instead, the impression is left that the program was sound only when 16 paid in for every one taking out. Thus, of course, when the ratio changed to 3.3 to 1, the program became “unsustainable.”

“They ignore the fact that in 1950 only about 15 percent of the elderly were eligible for benefits and that it was expected by all who were acquainted with the program that the ratio would, of course, change dramatically as a greater proportion of the elderly became beneficiaries.”

“What in fact happened is that when just about all the elderly first became eligible for Social Security benefits, about 1975, the ratio was 3.3 contributors to each beneficiary and the ratio has stayed that way for the past 30 years. As the baby boom reaches retirement age, as the administration says, the ratio is expected to drop for the long run to 2.0 or 1.9 workers to each retiree. But that is the size of the problem - a drop from 3.3 to 2 workers per retiree.”

http://www.tcf.org/Publications/RetirementSecurity/ballplan.pdf

But SS is pay as you go. The return to the worker is not much dependent on the interest paid on the Trust Fund. Congress has made some poor decisions, but the seed corn analogy is preposterous.

Arne,

If Social Security were entirely paygo you wouldn't have a trust fund. Moreover, at its inception, the program was intended NOT to be entirely paygo, to be a mix of a pagy and pre-funded program. It was only later that tax increases were delayed and benefit payments sped up, which in part led to large net transfers to early participants. So it wasn't a pure paygo program, either in terms of funding or in terms of the benefit formula.

Do these return on investment calculations include the economic value of the disability and survivor benefit insurance you're purchasing, or are the only calculated benefits the retiree benefits?

Michael,

The rate of return calculations generally include retirement, survivors and disability benefits. However, there isn't any explicit calculation of the insurance value of disability and survivors benefits over and above the money paid. (Insurance can have significant value even if it's not likely you'll receive it, since in the cases in which you DO receive it you're likely to need every penny you can get. That said, this applies to private sector insurance as well as to government-provided social insurance, so if folks are going to make those calculations they want to be uniform in doing so.)

Part of the reason why it seems that Treasuries held by the Social Security Trust Fund have value is that normally when Treasuries are held they have value to whoever holds them even if the Treasury has spent the proceeds from issuing them. However, when the Treasury holds Treasuries it is holding its own debt. In order to spend the value of the Treasuries to pay Social Security recipients, it must sell its own debt which is borrowing. Because of this, the only way in which it could have avoided needing to borrow in order to spend the value of the Treasuries in the Trust Fund would be to have not already spent the proceeds from the Treasuries.

If the Trust Fund were to withdraw Treasuries from the account, it would have to sell them for cash to give to Social Security recipients. When it is the Fed that sells Treasuries, it is not borrowing. Instead it is sterilization since the Treasury does not get additional funds to spend. However if the Treasury were to sell previously issued Treasuries, it would be the same as if they were issuing new Treasuries since they would be removing the ability to spend from the rest of the economy to transfer to Social Security recipients. This is the same as what would need to be done if there were no savings from previous years in the Trust Fund. It is different than if the Treasury issued the Treasuries and they were then bought and resold later since in such a case the reselling would be offset by the buying. If the Treasuries in the Trust Fund were resold, it would be using one Treasury to borrow twice since they would never have been bought.

In 2018 when the Social Security Trust Fund will need to borrow it will be in the same situation as if someone were spending more in a year than he was earning that year and needed to borrow because of this. However, he would only need to borrow if he didn’t have savings from previous years, which indicates that the Trust Fund really doesn’t have savings from previous years. The only way in which it can be said that the Trust Fund has savings from previous years is in the same way that someone could say that he had a savings account if it was a savings account where if he wanted to withdraw $100.00 the bank would say that he had to pay them $100.00. Without any savings, he would have to borrow the $100.00 to give to the bank to get his $100.00. He certainly wouldn’t be able to use such savings account as collateral for a loan!

If government borrowing is increased to replace the increased amount of government borrowing that goes to Social Security, it will harm the economy by increasing interest rates. To the extent that the additional borrowing causes the dollar to fall, interest rates will rise even more. In addition, as the employed percent of the population becomes smaller, GDP will decline in proportion to spending. This will cause the dollar to fall even more. As inflation increases because of these factors, Social Security obligations will increase to the extent that they are indexed to inflation.

The lack of funding of Social Security will become more apparent in 2011 when baby boomers start to retire. Since the government has depended on having more paid into the Trust Fund each year than is paid out and using the net inflow of funds for financing spending, even though there will still be a surplus until 2018 the government will have to increase borrowing before then to maintain the same level of spending.

Post a Comment