This hadn't gotten much discussion to date, but Sen. Obama has a component of his tax plan – called "Making Work Pay" – that would introduce significant progressivity into the tax side of Social Security. His plan is designed to partially or fully compensate workers for the employee share of the Social Security payroll tax – 6.2 percent of the 12.4 percent total tax. Workers would receive a refundable tax credit equal to 6.2% of wages up to $8,000, with a maximum credit of $500 per worker and $1,000 per couple. This is the source of the "tax cuts" Obama references for lower and middle income households. The Tax Policy Center assumes the credit phases out at 5 cents for each dollar of earnings above $75,000, meaning it declines to zero at $85,000.

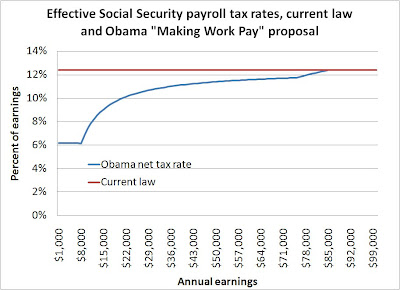

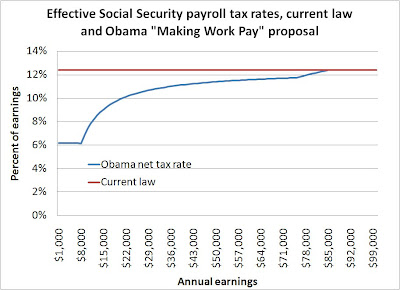

How does this change the effective Social Security payroll tax rate? The chart below shows the net payroll tax as a percentage of earnings for a single worker, with earnings levels from zero to $102,000 (the current cap on payroll taxes). The net tax rate is 6.2 percent of wages up to $8,000, gradually increasing to the statutory rate of 12.4 percent of wages by $85,000 and remaining constant up to the cap.

How would this affect the progressivity of the Social Security program taken as a whole? Remember, while the Social Security payroll tax may be regressive – a fact those on the left often cite – Social Security benefits are progressive. So you need to look at both taxes and benefits together to understand the progressivity of both current law Social Security and the program net of Sen. Obama's new tax credit.

Commonly Social Security progressivity is described through what is called the "money's worth ratio," which is the ratio of lifetime benefit received by a given individual to lifetime taxes paid. Both taxes and benefits are expressed in present value form, by discounting them at the government bond rate. To put things in terms of rates of return, a money's worth ratio of 1, in which lifetime benefits are equal to lifetime taxes, implies that the individual earned a rate of return on their payroll taxes equal to the return on government bonds.

Social Security's actuaries periodically calculate money's worth ratios for stylized workers at different earnings levels. The data used here come from a 2007 publication and are for single earners retiring in 2008. The SSA actuaries use four stylized lifetime earnings levels. They are:

Very low: Earns around 25 percent of the average wage, or around $10,500 per year. Around 20 percent of workers are in this group (meaning that this is the closest descriptor of their average earnings).

Low: Earns around 45 percent of the average wage, or around $18,900 per year. Around 22 percent of workers are in this group.

Medium: Earns around 100 percent of the average wage, or around $42,000 per year. Around 28 percent of workers are in this group.

High: Earns around 160 percent of the average wage, or around $67,000 per year. Around 21 percent of workers are in this group.

Maximum: Earns the maximum taxable wage each year, or around $102,000. Around 10 percent of workers are in this group.

The following table compares the money's worth ratios for each worker type, assuming retirement at age 65 in 2008, to what they would have been under the Obama proposal.

| Net money's worth ratio |

Earnings level | Current law | Obama payroll tax rebate |

Very low | 1.19 | 1.88 |

Low | 0.87 | 1.1 |

Medium | 0.64 | 0.71 |

High | 0.53 | 0.56 |

Maximum | 0.47 | 0.47 |

Assumes single male worker, retiring in 2008 at age 65 |

For instance, under current law a very low earner could expect to receive 1.19 times more in lifetime benefits than they pay in lifetime taxes. Since this comparisons are made to present values, discounted at the government bond rate of return (around 3 percent above inflation), this implies a rate of return on payroll taxes of around 4 percent above inflation. Under the Obama proposal, the net money's worth ratio for a very low earner would increase to around 1.88; total benefits would be the same, but lifetime taxes would be significantly lower. While comparisons are not straightforward, this implies an annual return on taxes of around 6.1 percent above inflation. Over a lifetime, the differences are significant.

The chart below uses the data above shows the "slant" of the Social Security program's progressivity under the Obama proposal. As can be seen visually, the system would be significantly more progressive than under current law. This may or may not be a good thing, according to your perspective, but it seems not to be something that should go undiscussed.

Now, what would the effect of the Obama plan be on Social Security's financing? After all, it effectively rebates part or all of the employee share of the Social Security payroll tax. The answer is that technically it would not affect Social Security's financing at all. These rebates, while based on the Social Security payroll tax, would be paid from general tax revenues – broadly speaking, income taxes. The total general revenue cost of the Obama proposal over 10 years is $728 billion, according to the Tax Policy Center.

That said, it's worth comparing the cost of Obama's proposal to those for personal retirement accounts, whose "transition costs" would also would be funded out of general revenue. The last detailed analysis of President Bush's personal accounts proposal I've seen was for the 2007 budget, which forecast a 10-year total cost of around $779 billion. In other words, the two policies cost around the same in the short term. Over the long-term, however, the Bush plan was designed to save those early contributions to help reduce Social Security costs. In other words, almost every dollar of costs in the near term was recouped in later years. The Obama plan, however, is simply an effective reduction in payroll taxes which would have increased costs over the long term.

Note that these numbers omit any reference to Sen. Obama's formal Social Security plan, which would also increase progressivity by imposing a surtax of 2 to 4 percent on all earnings above $250,000. Together, these policies would significantly alter Social Security's progressivity and – some might argue – shift it closer to a welfare-type program.

Read more!