The Bipartisan Policy Center invites you to Unprecedented Federal Debt: Putting Our Fiscal House in Order Hosted by Senator Pete Domenici, BPC Senior Fellow and Former Chairman of the U.S. Senate Budget Committee Luncheon Keynote Speaker: Congressman Steny Hoyer, U.S. House Majority Leader Keynote Address and Panel Discussion to be followed by Q&A Panelists: Wednesday, May 6, 2009, 9:00AM – 2:00PM St. Regis Hotel, Astor Ballroom, 923 16th Street NW Washington, D.C. RSVP to jonsurez@bipartisanpolicy.org or 202-637-1463

Thursday, April 30, 2009

Event: “Unprecedented Federal Debt: Putting Our Fiscal House in Order”

Obama Delves Into Social Security

Roll Call reports that President Obama raised Social Security reform at a townhall meeting in Missouri, where he reiterated his support for imposing new payroll taxes on workers earning above the maximum taxable wage, currently $106,800: President Barack Obama on Wednesday marked his 100th day in office at a townhall meeting in Arnold, Mo., where he said raising the payroll tax cap is the best way to help secure the future of Social Security. Obama, who spoke about the nation's retirement system in answer to a question from the audience, appeared to rule out accepting an increase in the retirement age, arguing that this would be a burden for workers. He added that "you could" cut benefits or "raise taxes," but then he said "the best solution" would be to increase the payroll tax cap. "For wealthier people, why don't we raise the cap?" he said. Obama indicated that he may have another of his White House summits — which have included experts, lawmakers, and stakeholders in various issues — on Social Security. But he noted that problems with Medicare are more urgent, using Medicare's financial shortfalls as a hook to promote his drive to overhaul health care. "We've got to have health reform this year, to drive down costs and make health care more affordable," he said. Obama's trip to Missouri, a presidential battleground state, shows that, after some foreign travel earlier this month, he is continuing his practice as president of scheduling events in "purple" states he will need for re-election. Obama last week held an event in Iowa, another important state on his electoral map. Bloomberg touches on Obama's comment's here.

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

New releases from SSA Office of the Actuary on rates of return, money’s worth, and immigration methodology

The following recurring notes based on the 2008 Social Security Trustees Report are now available on the Office of the Chief Actuary's internet site (http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/NOTES/actnote.html): In addition, a new non-recurring note (number 148) has been added. This note discusses the new projections of immigration for the 2008 Social Security Trustees Report.

CBO director’s blog: Projections of the Income and Spending of the Social Security Trust Funds

CBO director Doug Elmendorf has a nice explanation of where his group thinks Social Security finances are going, at least in the short term as the program recovers from the hit it has taken from the economic recession. Here's a clip: Over the 10-year period from 2009 through 2018, projected income and outlays have both declined significantly from our projections of a year ago—income is down by about $1.2 trillion (about 11 percent) and outlays are down by about $250 billion (about 3 percent) for that 10-year period (see Chart 1). Nearly all of the adjustments stem from changes in CBO's economic forecast: our projections for inflation, real GDP, and interest rates have all declined relative to those underlying our March 2008 baseline. Lower inflation affects both revenues and outlays through lower payroll taxes and smaller cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs). Similarly, lower real GDP would imply lower real wages—and therefore less revenue from payroll taxes and, over time, a lower initial benefit amount for new beneficiaries. Finally, because projected interest rates are lower, the trust funds are expected to earn less interest income. Outlays projected for the first few years are now higher than we estimated in 2008 because of the larger-than-expected COLA (5.8 percent) that took effect in January 2009. (For a discussion of CBO's projected COLA increases, see my recent blog. ) The decline in projected income and outlays has affected our projections of the trust funds' annual surpluses and balances (see Charts 2-4). Click here to read the whole blog post.

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

CBO director’s blog on effects of low inflation on Social Security benefits and financing

CBO director Doug Elmendorf has a new entry on the director's blog titled "Why CBO Projects No Social Security COLA for 2010 to 2012 Under Current Law." The background on projected inflation and COLAs is interesting and worth reading. But here's one point I hadn't thought of until he raised it: in any year in which there is no COLA there is also no adjustment in the Social Security maximum taxable wage, currently just under $107,000. Interestingly, the "tax max" isn't indexed for inflation, but for the generally higher rate of wage growth: The absence of COLAs will affect payments of Social Security taxes and the base for calculating benefits for new beneficiaries because it will affect the maximum amount of wages that are subject to Social Security, known as the taxable maximum. The Social Security Act specifies that the taxable maximum increases only in years in which a COLA occurs. Thus, under CBO's forecast, that maximum will be frozen until 2013. At that time, the contribution and benefit base will increases by the change in the national wage index since the last time a COLA was triggered. Following those current-law rules, CBO anticipates the base will hold steady at $106,800 for 2009 through 2012, and then jump to $118,200 in 2013, reflecting the cumulative change in the national wage index during the period of no COLAs. Inflation has only very small effects on system financing; a failure to adjust the tax max would have somewhat larger effects. For what it's worth, this aspect of the Social Security Act makes little sense. While I'm not particularly keen on raising the tax max, you want whatever rule is used for adjusting the cap to make policy sense. Adjusting the ceiling annually to maintain a constant percentage of total earnings subject to taxes makes sense to me; this would account not only for the growth of average wages but for changes in the distribution of earnings, such that if more earnings go toward the top then the cap would rise somewhat faster.

Chuck Blahous: Social Security myths are vanishing along with the surplus

Chuck Blahous, senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and the Bush administration's main man on Social Security reform, corrects some long-standing Social Security myths in the new issue of National Review. Well worth a read. 'When something is unsustainable," so goes the aphorism, "it tends to stop." Usually invoked about tangible phenomena, the old saw is equally true about unsustainable arguments. If a conception is unsustainable in the face of overwhelming evidence, it must die. Sometimes it dies with a whimper, sometimes with a bang. Mr. Blahous, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, formerly served as deputy director of the National Economic Council and executive director of the President's Social Security Commission. He is currently writing a book titled Social Security: The Unfinished Work.

In recent years a fashionable myth took hold on the left end of the American political spectrum: the myth of overly conservative Social Security projections. Social Security didn't really face a shortfall, it was said in these quarters. The supposed threats to the system amounted to a "manufactured crisis," based on faulty projections of the Social Security trustees, hyped by conservatives (and their enablers in the scorekeeping agencies) who wanted to destroy the treasured program.

The myth is exploding into pieces before our eyes, done in by evidence that can no longer be brushed aside. Yet such was its power that it continued to be invoked even as Social Security's projected near-term surpluses were disappearing. While some were renewing their efforts to deny the coming Social Security shortfall, the Congressional Budget Office was quietly providing updated projections for congressional staff. The new numbers showed that the FY2010 Social Security surplus would be almost wholly eliminated: a mere $3 billion, a pale shadow of the trustees' projection, last year, of $88 billion.

To the extent that things are turning out far worse than the trustees previously envisioned (to say nothing of the persistently more optimistic CBO, whose projections we will discuss later), this was primarily due to factors that no one could precisely have foreseen. Social Security this year faced the programmatic equivalent of a perfect storm: the recession depressed payroll-tax revenues at the same time that Baby Boomer benefit claims were surging, and the program was paying out its largest cost-of-living increase (5.8 percent) since 1982.

Even before the recent downturn, however, the myth was groundless and should never have gained traction. Those who bothered to look could see that there was never a plausible chance that the projected shortfall would vanish. The myth was sustained by various fallacies. Among them were:

Conflation of aggregate and per capita growth. The "National Jobs for All Coalition," in a typical example of this mistake, recently stated that the Social Security projections "assume that in years to come real GDP will grow much more slowly than it has over the past century or more, when it has averaged around 3.2 percent per year." The implication — indeed, often the overt statement — of this line of argument is that without this inexplicable projection of a growth slowdown, the problem would be much smaller.

But total growth depends on a number of factors, and some of those factors are changing. The Social Security projections were not arbitrarily assuming a decline in productivity growth per worker — they were taking into account a very realistic projection of a decline in the number of workers added to the labor force every year, as the Baby Boomers head into retirement. From 1963 to 1990, annual labor-force growth was never lower than 1.2 percent, and reached as high as 3.3 percent. Now, net labor-force growth is expected to drop to 0.5 percent by the end of the next decade and stay there.

If the workforce grows by less than one-third the rate it used to, we can quite reasonably expect the economy to grow more slowly as well. This demographic reality was glossed over by some, to create the misimpression of arbitrarily conservative future economic assumptions.

Overstatement of the relative impact of economic growth. In a closely related example, a recent MarketWatch column titled "Why Social Security Isn't Going Broke" stated: "The actuaries' own low cost projection assumes an average annual growth rate of 2.9 percent between now and 2085. . . . Guess what? Under the actuaries' low cost projection, the Social Security system never runs out of money!"

This rather makes it sound as though faster growth by itself will eradicate the problem, doesn't it? But this "low-cost" projection of the trustees isn't only about faster economic growth. Rather, it's a hypothetical illustration of what could happen if virtually every variable improbably breaks in the direction of a smaller Social Security deficit. The "low-cost projection" assumes that fertility rates permanently return to levels not seen since the 1970s. It assumes that longevity grows less over the next 75 years than it has over the past 30. It assumes that inflation after 2010 never rises above 1.8 percent. And so on. The scenario is a compendium of every rosy outcome (from a fiscal perspective) that one can dream up. It is, in short, not plausible.

Misrepresentation of the projection record of the Social Security trustees. Another longstanding myth is that the trustees' past projections have proven too conservative. In a typical statement from a 2005 budget hearing: "They [the trustees] have been wrong because they have consistently understated economic growth. I believe, in all likelihood, they are wrong again."

This allegation has developed in direct contradiction of the facts. As I pointed out in a 2007 paper, the trustees' projection record since the last major reforms is one of impressive accuracy, although they have been slightly too aggressive — that is, they have, to date, somewhat overstated the program's fiscal health.

The myth of excess past conservatism has been fed by cherry-picked references to the few, unrepresentative trustees' reports that were in fact too conservative: those of the mid-1990s, made just before an unexpected surge in economic growth caught all government forecasters (not only the trustees) by surprise.

Amazingly, if the CBO's projections are off by a mere $3 billion and the program enters cash deficits next year, the deficit date will have arrived sooner than predicted in every single trustees' report since the 1983 reforms. In other words, not a single projection over all that time will have been conservative enough. If the projections' critics haven't been 180 degrees off of empirical reality, they've been 179.9.

The acceleration of Social Security's difficulties is leaving egg on many a face — not only those of the most vocal problem-deniers, but on those of other forecasters as well. Just last year, CBO, on the eve of this sudden downturn, inexplicably revised the long-term Social Security assumptions to be more optimistic. CBO's projection changes were mysterious at the time, and look startlingly ill-timed now. One assumption they made was that 2001/03 tax policies would expire, along with relief from the AMT, and that federal income-tax collections would be allowed to grow to exceed permanently the historic highs. However defensible as a literal application of "current law" in the near term, no responsible agency should have adopted such an implausible basis for lowballing, in its communications to legislators, the estimated size of the long-term shortfall.

Even stranger was CBO's sudden decision to increase its long-term real-wage-growth assumptions to 1.4 percent annually — more than 50 percent higher than the historical average over the last 40 years. This put CBO's latest estimate near the faulty 1983 assumption of 1.5 percent, which proved to be far too aggressive. CBO's change was never adequately explained, and its implementation on the eve of current economic difficulties has turned out to be a masterpiece of mistiming.

Whatever the explanations for these various missteps, one thing is now clear: Not only have the trustees' projections not been too conservative, we now face a bigger problem even than previously projected. The refutation of the mythmakers has arrived in the form of an economic crisis that will exact a heavy price: from all of us, including those who saw the problem coming, those who denied it, and those who were innocently oblivious. People from every camp will need to work together to fix the problem that now faces us. Reality can sometimes be an unforgiving teacher. Let's hope that enough of her pupils learn and respond.

Public versus private pension stewardship

The recent market downturn and financial crisis has seen many argue that the private sector cannot be trusted to manage things like pensions and the government is a far better steward of these long-term commitments. The state of Social Security, which has gone unaddressed despite years – actually decades – of warnings from the program's Trustees, speaks against this. But here's another interesting example documented by the Financial Times and Megan McArdle comparing the funding status of private sector defined benefit pension plans to pensions for public sector employees. McArdle points out: According to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, which regulates and insures pensions, the total deficit in private plans covering about 34 million workers was a little over $10 billion as of September 2008. That's almost certainly multiplied quite a bit since then. But the current underfunding in public plans, which cover about 22 million workers, seems to be something north of a trillion dollars. In other words, private plans are underfunded by around $295 per employee. Not a good thing, but could be worse. A lot worse, as it turns out, if you compare to public sector plans where per employee underfunding amounts to around $45,500. No wonder, as I commented yesterday, public sector funds aren't so keen on honest accounting.

Washington Post proposes Social Security changes to address deficits

In an editorial today, the Washington Post proposed several steps to help address current and future budget deficits. Among them are two that would reduce Social Security benefits for future retirees: Raise the Social Security retirement age beyond the slated increase to 67 to 68. As people live longer, it makes sense that they work a bit longer, too. This change could be made gradually, and eventually would save $10 billion a year, with savings left over to strengthen the disability program to protect manual laborers and those who need to retire early. Reduce Social Security benefits for the well-off while protecting those who depend on the program. As controversial as Social Security reform is, every serious policy expert recognizes the need for changes, including benefit reductions. Better targeted reductions than across-the-board cuts. Together, these steps would be almost sufficient to address the long-term Social Security deficit. This page published by the Social Security Office of the Actuary includes estimates for these reform provisions as well as a number of others.

CBO presentation on decline in Social Security surplus

The Congressional Budget Office yesterday made a presentation to the Social Security Advisory Board regarding the recession-induced decline in the Social Security surplus. I don't believe the presentation is available online, but I've uploaded a copy here.

SSAB Presentation - 2009 04 - Trust Fund Charts

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Upcoming event: Retirement Finance in the Wake of the Bubble and Longer-Term Implications

On Wednesday, May 6, 2009 at 2:00 PM the American Enterprise Institute and the Brookings Institution will hold a joint event, "Retirement Finance in the Wake of the Bubble and Longer-Term Implications." The event will be at the Wohlstetter Conference Center, Twelfth Floor, AEI 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 The deflated credit bubble has brought huge losses and tensions to retirement finance. It has caused severe underfunding of corporate pensions and a deepening crisis among state and municipal pension plans. In addition, in an ill-advised move, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation shifted its asset allocation toward equities just in time for the market crash, and Social Security's annual surplus has all but disappeared. Panelists: Andrew G. Biggs, AEI Gary Burtless, Brookings Institution Douglas J. Elliott, Brookings Institution David C. John, Heritage Foundation Moderator: Alex J. Pollock, AEI Click here for more information.

Are the 1950s ideas of "retirement" and its financing viable fifty years later? What long-term reforms are required? These and other questions will be discussed by retirement finance experts, including former Social Security Administration principal deputy commissioner Andrew G. Biggs, now at AEI; labor economist Gary Burtless and Douglas J. Elliott, former principal researcher for the Center on Federal Financial Institutions, both from the Brookings Institution; and David C. John of the Heritage Foundation, codeveloper of the automatic individual retirement accounts proposal. AEI's Alex J. Pollock will moderate.

Market-oriented actuaries need not apply

Pensions & Investments reports that the Montana Public Employees' Retirement Board and the Montana Teachers' Retirement System, both of Helena have issued RFPs for actuarial consulting services that threaten to disqualify bidders if they support market valuation of pension liabilities. What's the big deal? Currently, Montana discounts its future benefit obligations at an interest rate of 8 percent, which is the expected rate of return on its investment assets. However, 8 percent is a risky rate of return, meaning we can't simply assume that the fund will return that amount. Market-oriented actuaries would use a lower risk return, on the order of 3-3.5 percent, says P&I. This risk neutral approach better captures the risk to the pension provider that their risky investment portfolio might be insufficient to fund full benefits in the future. To illustrate the difference, imagine if the pension plan had benefit liabilities of $100 million beginning 20 years from now. At an 8 percent discount rate, the present value of that liability would be only $21 million. At a 3 percent discount rate, however, the present value of that $100 million future liability would be $55 million, over twice as much. You can see how big a difference market analysis makes in assessing the level of underfunding in a pension plan. This also tells us something about the state pension providers in that they seem so eager not to hear what market analysis has to say. Here's the substance from the RFPs: 3. One (1) Market Value of Liabilities Report. Briefly state the position of the Primary Actuary and of the Actuarial Firm on this topic. Please submit any written documentation in which the position of the Primary Actuary or the Actuarial Firm has been stated. If the Primary Actuary or the Actuarial Firm supports MVL for public pension plans, their proposal may be disqualified from further consideration. (Section 4.7) 4.7 Market Value OF Liabilities (MVL) Much has been written and discussed regarding the pros and cons of using market value of liabilities in the actuarial valuations of public defined benefit plans. Briefly state the position of the Primary Actuary and of the Actuarial Firm on this topic. Please submit any written documentation in which the position of the Primary Actuary or the Actuarial Firm has been stated. If the Primary Actuary or the Actuarial Firm supports MVL for public pension plans, their proposal may be disqualified from further consideration. This paper, co-authored with Kent Smetters and Clark Burdick, applies market analysis to the cost of protecting Social Security personal accounts against stock market risk. While the context is different, the underlying difference between the "expected cost" approach and the "risk neutral" approach is the same.

Monday, April 20, 2009

EBRI Releases 2009 Retirement Confidence Survey

The Employee Benefit Research Administration has released the 2009 Retirement Confidence Survey. Here are some highlights, and click here to access the whole document. RECORD LOW CONFIDENCE LEVELS: Workers who say they are very confident about having enough money for a comfortable retirement this year hit the lowest level in 2009 (13 percent) since the Retirement Confidence Survey started asking the question in 1993, continuing a two-year decline. Retirees also posted a new low in confidence about having a financially secure retirement, with only 20 percent now saying they are very confident (down from 41 percent in 2007). THE ECONOMY, INFLATION, COST OF LIVING ARE THE BIG CONCERNS: Not surprisingly, workers overall who have lost confidence over the past year about affording a comfortable retirement most often cite the recent economic uncertainty, inflation, and the cost of living as primary factors. In addition, certain negative experiences, such as job loss or a pay cut, loss of retirement savings, or an increase in debt, almost always contribute to loss of confidence among those who experience them. RETIREMENT EXPECTATIONS DELAYED: Workers apparently expect to work longer because of the economic downturn: 28 percent of workers in the 2009 RCS say the age at which they expect to retire has changed in the past year. Of those, the vast majority (89 percent) say that they have postponed retirement with the intention of increasing their financial security. Nevertheless, the median (mid-point) worker expects to retire at age 65, with 21 percent planning to push on into their 70s. The median retiree actually retired at age 62, and 47 percent of retirees say they retired sooner than planned. WORKING IN RETIREMENT: More workers are also planning to supplement their income in retirement by working for pay. The percentage of workers planning to work after they retire has increased to 72 percent in 2009 (up from 66 percent in 2007). This compares with 34 percent of retirees who report they actually worked for pay at some time during their retirement. GREATER WORRY ABOUT BASIC AND HEALTH EXPENSES: Workers who say they very confident in having enough money to take care of basic expenses in retirement dropped to 25 percent in 2009 (down from 40 percent in 2007), while only 13 percent feel very confident about having enough to pay for medical expenses (down from 20 percent in 2007. Among retirees, only a quarter (25 percent, down from 41 percent in 2007) feel very confident about covering their health expenses. HOW WORKERS ARE RESPONDING: Among workers who have lost confidence in their ability to secure a comfortable retirement, most (81 percent) say they have reduced their expenses, while others are changing the way they invest their money (43 percent), working more hours or a second job (38 percent), saving more money (25 percent), and seeking advice from a financial professional (25 percent). Among all workers, 75 percent say they and/or their spouse have saved money for retirement, one of the highest levels ever measured by the RCS. IGNORANCE STILL A MAJOR FACTOR: Many workers still do not have a good idea of how much they need to save for retirement. Only 44 percent of workers report they and/or their spouse have tried to calculate how much money they will need to have saved by the time they retire—and an equal proportion (44 percent) simply guess at how much they will need for a comfortable retirement.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

New paper: “Does It Pay to Work? The Case for Cutting the Social Security Tax for Workers near Retirement”

I have a new Retirement Policy Outlook released by AEI today. The paper, "Does It Pay to Work? The Case for Cutting the Social Security Tax for Workers near Retirement," focuses on the marginal returns paid by Social Security to workers near retirement. The marginal return is the additional benefits earned for an additional dollar of taxes paid, and is a key incentive affecting decisions to continue working or leave the workforce and retire. Here the opening: Social Security's 12.4 percent tax is the largest paid by most workers and Social Security benefits are the largest income source for most retirees. An individual considering whether to work or retire might ask, "What's in it for me? If I continue to pay into Social Security, how much additional benefit will I receive?" The answer: not much. The typical individual who works for an additional year before retiring will receive only 2.5 cents in additional benefits for each dollar of extra taxes paid to Social Security. This translates to a marginal rate of return of -49.5 percent. One reform to extend working years and enhance income security in retirement would be to reduce or eliminate the payroll tax for individuals above a given age. Marginal returns are low for men because the Social Security benefit formula counts only their highest 35 years of earnings in calculating benefits; if an additional year of work isn't in the highest 35 – part time work comes to mind – then no additional benefits are received. Marginal returns tend to be low for women due to the presence of spousal benefits, under which a lower-earning spouse receives the higher of her own benefit or half her spouse's benefit. Women who receive auxiliary benefits, as most do, will in general face a -100 percent marginal return for additional taxes paid. The argument here is that if we want older Americans to remain in the workforce, we need to give them an incentive to do so. The current Social Security benefit formula pays very little extra benefits to people who choose to work longer, which weakens incentives to delay retirement. While a number of different policies could improve marginal returns, I focused here on reducing the payroll tax for older workers. It's an easily understandable way to improve incentives to work and I think is worth considering as part of larger reforms. This Retirement Policy Outlook is drawn from a longer paper co-authored with David Weaver and Gayle Reznick of the Social Security Administration, which was released by SSA earlier this week. That paper includes all the RPO's information on marginal returns, as well as analysis of lifetime rates of returns and a third measure we call incremental returns. The incremental return looks at the benefits a married person could receive by working, over and above the spousal benefits they would receive based on their spouse's earnings record. For example, a woman who works might receive only a little bit more benefits based on her own earnings record than she would receive if she had not worked and simply collected a spousal benefit. This structure means that most of the taxes she pays over her lifetime don't generate new benefits for her, and thus serve as a disincentive to work. Married women are generally held to be more responsive to tax rates than unmarried women or men, so it can be counterproductive if married women face the highest net tax rates at the margin.

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

How does Social Security affect tax progressivity?

The Economist weighs in on tax day on how the Social Security program affects the overall progressivity of the tax code. People on the right often point that that the vast majority of income taxes are paid by high earners. On the left, however, folks point out that payroll taxes are a large and regressive tax that often isn't included in these kinds of analysis. That's a fair point. However, as I discussed here, Social Security is a program in which taxes and benefits are linked. And low earners generally receive more benefits relative to their taxes than do high earners. So the progressivity of the benefit formula needs to be factored in. This chart shows the lifetime net Social Security tax rate paid by current retirees of different earnings levels. The net tax rate reflects the legal tax rate – 12.4 percent of earnings – minus the benefits generated by those taxes. If you received lifetime benefits equal to 12.4 percent of your lifetime earnings, for instance, your net tax rate would be zero. If you received even more than that, your net taxes would be negative – this means that you receive a subsidy from the program. As the chart shows, for low earners the net tax rate is highly negative, meaning that they receive significantly more from the program than they pay in. Subsidies are smaller for middle earners, and non-existent for individuals in the top 20 percent of the earnings distribution.

Obama’s Truly Exceptional Budget and Tax Plans

I have a short piece in AEI's online magazine The American about President Obama's budget projections. The key point is that, while higher economic growth generally leads to lower deficits, Obama's own budget includes optimistic projections for economic growth alongside projections for deficits that dwarf those that Obama criticized President Bush for running. Hypocrisy, they say, is vice's tribute to virtue. In politics, we praise candidates who pledge to boost economic growth and curb the deficit, however implausible the promises, if only because they represent an aspiration to effective government. Yet even by this lax standard, President Obama's budget is striking for its lack of ambition. Despite predicting almost implausibly strong economic growth over the next ten years, the administration itself projects enormous budget deficits. Click here to read the whole article.

Monday, April 13, 2009

Ensure Your Retirement Bliss by Working Longer: John F. Wasik

Bloomberg columnist John F Wasik has a good article outlining the benefits of delaying retirement, based on a new brochure published by SSA (that, full disclosure, I'm proud to have worked on during my time at the agency). This is the kind of follow-on publicity we were hoping to generate as the new pamphlet, "When To Start Receiving Retirement Benefits," was being developed. Both the pamphlet and Wasik's column are worth a read.

Tuesday, April 7, 2009

Dean Baker in USA Today: Hands off Social Security

Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research provides the opposing view to today's USA Today editorial. One quote is worth highlighting: The Congressional Budget Office projects that Social Security, by drawing down its trust fund, will be able to pay benefits until the year 2049 with no changes whatsoever. Dean helpfully includes a link to the CBO report that, as of last year, projected trust fund solvency through 2049. A friend points out that, leaving aside how much Social Security's finances seem to have declined in the last year, the CBO report includes an important footnote regarding the trust funds: The Social Security trust funds (the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund and the Disability Insurance Trust Fund) serve mainly as an accounting mechanism to track revenues and outlays for Social Security. The trust funds' balance summarizes the cumulative accounting history of the Social Security program in a single number, because the balance equals the present value of all past revenues minus the present value of all past outlays. The funds' balance also represents the total amount that the government is legally authorized to spend on Social Security. See Congressional Budget Office, Federal Debt and the Commitments of Federal Trust Funds, Issue Brief (October 24, 2002; revised May 6, 2003). In other words, the trust fund balance is pretty much like a credit card statement: it shows how much we have borrowed from Social Security over the years, plus interest. But since we're the ones who borrowed the money, we're the ones who'll have to pay it back: there's no bars of gold in some vault that constitutes the trust fund. Rather, the fund is simply an obligation by the government to raise taxes beginning in a few years – and fewer years than we'd thought a year ago. Lacking the trust fund, we'd face a choice between raising taxes and cutting benefits; with the trust fund, the choice is biased toward raising taxes, at least until the fund is exhausted. But we shouldn't pretend the choices are something other than what they are. A second point. Dean says: It is truly incredible, and unbelievably galling, that anyone in a position of responsibility would suggest defaulting on the government bonds held by the Social Security trust fund at the precise moment that the government is honoring trillions of dollars of bonds issued by private banks. While the government has no legal or moral obligations to pay off the banks' debts to wealthy investors (who presumably understood the risks they were taking), the Social Security bonds carry the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Dean continually – and, one has to assume, deliberately – confuses the relationship between the trust fund's bonds and benefits owed to individuals. He says there's a relationship between the two, while the law says there isn't. In other words, if Congress chooses to alter Social Security benefits so that bonds need not be redeemed that's NOT a default on the trust fund, as much as Dean would like to says that it is. To claim that reducing benefits constitutes a default on the trust fund is simply incorrect, which Dean surely knows. Moreover, this is all a bit ironic given that Dean has been one of the leading opponents of personal accounts, in which individuals would have an ownership right in their assets. That is, if an account holder purchased a government bond, the government could no more default on that bond than it could on a bond owed to Wall Street or to the Chinese. Those are some pretty big friends to have. But under the current Social Security set-up – which is the one Dean supports, and is designed in pretty much the way he and others on the left would design it – the government can alter the deal any time it sees fit. If your political worldview says that people should be highly dependent on the government for their retirement income that's fine, but you can't complain later if the government chooses to alter the deal. That's the downside of dependency, folks. The Supreme Court has ruled that there's no contractual obligation involved with Social Security taxes and benefits. That may well be the best way to run the program policy-wise, but it seems rich to then claim that any change to benefits violates a contract.

USA Today: Recession adds urgency to Social Security fix

USA Today editorializes on the need for Social Security reform: Our view on retirement: Recession adds urgency to Social Security fix Vanishing surplus underscores need to ensure long-term solvency. With 401(k)s and pension funds taking a hit recently, perhaps it should come as no surprise that Social Security is hurting as well. While the program is not invested in the stock market (as privatizers wanted to do), it is dependent on a steady stream of payroll tax revenue, which drops in times like these when large numbers of workers lose their jobs or see their income decline. Preliminary damage estimates by the Congressional Budget Office aren't pretty. Projected Social Security surpluses over the next decade have all but disappeared. Next year's operating surplus, previously estimated at $86 billion, is now $3 billion. Ten years of cumulative surpluses, once seen at about $703 billion, are now projected at $83 billion. In short, the long-predicted Social Security crisis is arriving sooner than expected, underscoring the need to ensure the program's long-term solvency now. The global recession, and the losses in other forms of retirement savings, may appear to provide a reason for delaying unpleasant reforms yet again, but this is actually an ideal time to act. Each year that the U.S. government fails to address its massive retirement and health care obligations raises the prospects of it defaulting on its debts, inflating its way out of them, or imposing punitive taxes to pay them off — any of which would cause greater misery than the changes needed to stabilize the system. A commitment to shore up Social Security would serve as a clarion statement that the U.S. economy is a sound long-term investment. It would also give confidence to ordinary Americans that Social Security will be around when today's young and middle-aged workers retire. For all the talk about "trust funds," Social Security essentially operates on a cash-in, cash-out basis. And once the amount being paid out in benefits exceeds the amount coming in — now expected in 2017 — the government will have to borrow billions of dollars to cover the difference. Compared with solving the health care problem, Social Security should be a walk in the park. As a program it works just fine, but it is unsustainable as the result of increasing life spans, rising benefits, and the aging of Baby Boomers. In 1935 the average retiree lived about 13 years after the age of 65. Today the average is 19.5 years. Preserving Social Security for the long term isn't that complicated. It can be done by gradually raising the retirement age for able-bodied workers, curbing growth in benefits and making high-income workers pay more payroll taxes. The longer a solution is delayed, the more painful it will become. Early this year President Obama signaled an interest in addressing the problem. And a bipartisan group of senators began discussing a plan to fix the program, largely by enticing people to stay in the workforce longer. House Democrats shot this effort down. In addition to the normal reluctance to taking a tough but necessary stand, they reasoned that responsible action would undermine some of the political gains they made after President Bush's unpopular bid to partially privatize the program in 2005. Maybe so, but the numbers don't lie. Social Security is in trouble. The recession is a reason to fix it now, not an excuse for further delaying the inevitable.

Monday, April 6, 2009

New poll: NCPSSM: Americans Support Protecting Social Security Benefits

The National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare released the results of a new poll of Baby Boomers and older Americans regarding the future of Social Security. While the results show greater concern for Social Security's future than the National Committee generally projects – 14 percent say it is in crisis and an additional 49 percent say it has major problems, while the National Committee tends to downplay the problem – nevertheless the results regarding policy solutions appear favorable to the left. The survey asked, "Which of these four ways to insure the future of Social Security would you be most in favor of?" While I would have phrased the questions differently – I have seen polls showing that progressive benefit reductions rank higher than all policy options other than increasing the wage cap – and would have included younger respondents, who are most likely to be affected by Social Security reform, these results do pose a challenge to those who would wish to fix Social Security finances entirely on the benefit end. Click here to read the full results and cross tabs.

Friday, April 3, 2009

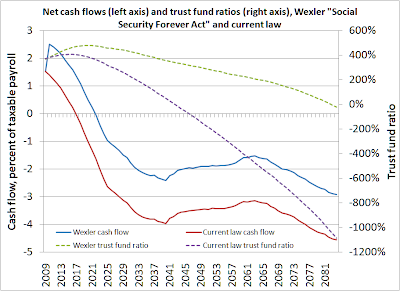

Wexler reintroduces Social Security (almost) Forever Act

Florida Rep. Robert Wexler reintroduced his "Social Security Forever Act," which would impose a 6 percent surtax on earnings above the taxable maximum of $106,800. The tax would be split evenly between employers and employees, and no additional benefits would be paid based on the extra taxes. Off the top of my head, this would increase Social Security's revenues by around 1 percent of payroll, since around 16 percent of total earnings are above the current wage ceiling and Wexler would tax 6 percent of them, which equals 0.96 percent of payroll. Using the GEMINI microsimulation model I simulated the effects of Wexler's plan on Social Security solvency. The chart below shows both the system's net cash flows and its trust fund ratio (the trust fund balance divided by that year's benefit payments), both compared to current law. Trust fund solvency is clearly what Wexler was aiming at here, as the trust fund ratio would remain positive throughout 75 years but become insolvent soon thereafter. However, this plan doesn't approach so-called "sustainable solvency" in which the trust fund would remain healthy after 75 years. Moreover, the plan depends on building new trust fund surpluses today to help finance deficits in the future, the same philosophy taken in the 1983 reforms. There's not much point in belaboring the problems with that approach. Annual cash flows, while better in every than under current law, still run pretty significant deficits beginning in around 2022, versus (we think) 2017 under current law. I'm not sure a trust fund-based approach is going to be that effective in truly prefunding future cash flow deficits, but at least Rep. Wexler has the guts to put his plan on the table – which is more than can be said about most Members of Congress, Republicans or Democrats.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

IBD: Entitlement Crash

Investors Business Daily weighs in on the declining Social Security surplus and argues for reform based on personal accounts. I took issue with some of their reasoning in this older post.

GOP Budget proposal for Social Security: How much of the deficit would it fix?

Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) introduced the House Republican budget proposal, which includes provisions to help reduce future Social Security deficits by reducing benefits for high earners. The full description is available here, but the key is to reduce the 15 percent replacement factor in the Social Security benefit formula by 0.25 percentage points per year beginning five years prior to the projected insolvency of the program. Since the trust fund is currently projected to be depleted in 2041, this implies benefit reductions beginning in 2036. Some background: Social Security has three "replacement factors" by which benefits are calculated. For a new retiree in 2009, Social Security replaces 90 percent of the first $744 in monthly earnings, 32 percent of earnings between $745 and $4,483, and 15 percent of earnings above that level. Reducing the 15 percent replacement factor wouldn't affect most retirees because their earnings during their working years weren't high enough to enter into it. I've estimated the effects of this provision on Social Security solvency using the Policy Simulation Group's GEMINI microsimulation model. The parameters imply that the 15 percent replacement factor would go to zero after 60 years, so I have assumed the policy continues from 2036 onwards. Under these assumptions, the policy in the House Republican budget would reduce the 75-year Social Security actuarial deficit by around 5 percent, from 1.70 percent of taxable payroll to 1.61 percent. The key reason for the small effects is the delay: were the proposal started sooner it could do go much further toward addressing the problem, and without impacting low earners who rely on Social Security the most. The House GOP proposal solves less of the long-term deficit than President Obama's tax plan – which addresses around 15 percent of the shortfall – but they target some of the same people, albeit at different times of their lives. Obama's plan to impose a surtax on individuals earning over $250,000 would hit high earners during their working years; the House GOP's plan would hit high earners during their retirement years. It's great that the House GOP has put some ideas on the table, just as it was great when then-Sen. Obama did. The key is for both to do more, do it sooner, and – hopefully – do it together.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

WSJ: White House to look at GOP Social Security reform plan

The Wall Street Journal Here's what the Journal had to say: John D. McKinnon reports on politics. Social Security reform, largely ignored since President George W. Bush's ill-starred initiative in 2005, could be resurfacing soon. On a conference call with reporters Wednesday where he generally blasted Republican budget proposals, a top Obama budget official said the administration would have to take a close look at the GOP proposal on Social Security, and hinted that the White House would have more to say on the issue soon. Rob Nabors, deputy director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, reiterated the administration's view that the most urgent budget problem in the entitlements area is not Social Security but the soaring cost of health care, which threatens fiscal disaster for the U.S. because of programs like Medicare and Medicaid. One of President Barack Obama's top three policy objectives for this year is a broad health-care overhaul that would begin to rein in those costs. But Nabors added that administration officials would spend some time "looking at" the GOP proposal on Social Security, and promised that the public will be seeing more from the administration on the issue as the budget process unfolds. The White House is expected to roll out its complete budget proposal in late April or early May. The administration is under pressure from lawmakers of both parties – including Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad (D., N.D.) – to address Social Security, perhaps through a commission process. The Republican proposal includes a future cap on Social Security benefits for some younger and wealthier beneficiaries. The Social Security trust fund is projected to be completely tapped out by 2041, although retiring baby boomers are expected to create a significant burden on the nation's finances much sooner, within the next decade.

reports that on a conference call with reporters, top White House budge official Rob Nabors said they would examine the reform outline put forward by Rep. Paul Ryan, the top Republican on the House budget committee, and would have more to say on the subject of Social Security reform soon. This is good news, as substantive prospects for reform are actually higher now than in the past: many Republicans are willing to compromise on the subject of personal accounts, and Democrats who previously denied the problem may be chastened by the recent downturn in Social Security's finances. Let's hope so.

What is the debt-to-GDP ratio if we include the Social Security and Medicare trust funds?

As deficits rise and the Baby Boomers retire, the burdens of government spending on the economy are becoming more obvious. The most common measure of where we are and where may be going is the ratio of debt to gross domestic product. This ratio, more so than the simple dollar value of the debt, indicates the economy's capacity to support government borrowing. But an important question is how to measure the debt to GDP ratio. All measures include the publicly held government debt, which means Treasury bonds held by everyone from Wall Street investors to ordinary folks saving for retirement. However, it's not clear whether we should includes intragovernmental debt, which is primarily composed of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. Many on the left don't like to count the Social Security and Medicare unfunded obligations – which total in the tens of trillions of dollars – as true "debt." That's fine. As some have correctly pointed out, future Social Security and Medicare benefits in excess of what the trust funds can finance are obligations, not liabilities, and can be changed at any time. (It's ironic that many on the left don't wish to change them, but that's another story.) That is, implicit debt isn't the same explicit debt. But folks on the left are also adamant that the Social Security and Medicare trust funds are true debt – as good as any debt issued to Wall Street, as (say) Dean Baker argues. Ok, that's fine. But if so, shouldn't we count Social Security and Medicare debt when we calculate debt-to-GDP ratios? I can't see why not. And when we do, it tells a very different picture about the evolution of public finance in the U.S. The chart below is drawn from OMB historical data from 1940 through 2007. It shows both publicly held debt – the kind we usually think about – as well as intragovernmental debt, which includes the Social Security and Medicare trust funds as well as other government trust funds (the highway trust fund, etc.). As of 2007, publicly held debt equaled 37 percent of GDP. Not a problem, except that CBO projects that the recession and financial crisis coupled with President Obama's spending plans, by 2018 the publicly held debt could more than double, to 82.4 percent of GDP. Most people would consider that a problem. But then add to that the intragovernmental debt that many people insist must be treated as just as "real" as publicly-held debt. There don't seem to be good projections of future intragovernmental debt, but let's just assume that the ratio to GDP remains the same. (This isn't implausible; while the Medicare trust fund is winding down, the larger Social Security trust fund is projected to peak in the 2020s.) In that case, by 2018 total government debt will reach 111 percent of GDP. That level would put us somewhere between where Sudan and Jamaica are today, and fifth from highest globally. While there isn't a strict threshold at which debt becomes unsustainable – what matters is the growth rate of nominal debt relative to the growth of nominal GDP – even the IMF and World Bank's debt sustainability framework adjusted for a strong country like the U.S. would frown on debt at that level. Moreover, the total debt level as of 2018 would be only slightly lower than the historical peak of 121 percent in 1946, when we had just finished fighting a war around the globe. But unlike the debt issued to fight World War Two, this debt won't be incurred in the cause of freedom but in the cause of political convenience – a fight not to defeat foreign enemies, but political opponents who say that long-term spending must be reined in.

Broder blasts Pelosi on entitlement reform

Columnist David Broder, in yesterday's Washington Post, criticizes House Speaker Nancy Pelosi for her opposition to a commission to examine entitlement reforms, and for her resistance to entitlement reforms in general: The roadblock in chief is Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the House. She has made it clear that her main goal is to protect Social Security and Medicare from any significant reforms. Pelosi has not forgotten how Democrats benefited from the 2005-06 fight against Bush's effort to change Social Security. Her party, which had lost elections in 2000, 2002 and 2004, found its voice and its rallying cry to "Save Social Security," and Pelosi is not about to allow any bipartisan commission to take that issue away from her control. The price for her obduracy is being paid in the rigging of the budget process. The larger price will be paid by your children and grandchildren, who will inherit a future-blighting mountain of debt. The political angle shouldn't be forgotten. While fixing Social Security and Medicare could cement in place Pelosi's long-term reputation – Speaker Tip O'Neill is remembered for helping broker the 1983 Social Security reforms – reform will also involve making difficult choices and giving up a convenient stick with which she has successfully beat Republicans in recent years. You can't accuse the GOP of cutting Social Security at election time if you just worked with them to make it sustainable. It's a shame there's not more leadership and vision in evidence.

Growing Costs: The Left’s new narrative on entitlements relies on statistical sleight of hand

I have a piece on National Review Online discussing the debate over what is driving entitlement costs: population aging versus rising health care costs. To address the rising costs of federal entitlement programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, it's important to know what is causing these cost increases to begin with. For years, the entitlement crisis was assumed to be driven by the aging of the American population, a trend that pushes 10,000 seniors per day onto benefit rolls without balancing them with taxpaying workers. Rising life spans and lower birth rates will permanently increase the ratio of retirees to workers, driving costs — and taxes — higher. I argue, based on a longer article for AEI, that the role of health care cost inflation has been significantly overstated, particularly by some activists who wish to avoid tough choices on entitlements while pushing to nationalize health care for working age Americans.

But this view, according to a narrative now dominant in liberal policy circles, is not correct. These critics note, accurately, that costs are rising too quickly for shifting demographics to explain them entirely. But this new narrative diminishes aging's role too much, and opens the door to intrusive federal control over private-sector health care.

Recession could cut life of Social Security trust fund by five years

I was asked yesterday how the current recession, which has significantly reduced the Social Security surplus, might affect the life of the trust fund. I put together some back-of-the-envelope numbers that at least guestimate the effects. These are necessarily approximations and mix CBO and SSA projections together (CBO, because they have they latest data available; SSA, because the Trustees projections for solvency remain the most prominent and well-understood). Take them with a grain of salt, but qualitatively I believe they should get in the ballpark. Here's how CBO summarizes the differences in Social Security cash flow – meaning tax income (payroll tax revenues plus income taxes levied on retirement benefits) minus benefits and administrative costs – between their March 2008 budget projections, which also formed the basis for their August 2008 long-term Social Security projections, and their current March 2009 projections: Next I calculate the present value of these new-found losses to tax income. Discounted at a nominal interest rate of 5.4 percent, which is a rough average of the 10-year Treasury bond rate from CBO's latest economic projections, this produces a present value as of 2009 of $621 billion. In other words, these future declines in payroll tax revenues are roughly equivalent to the trust fund balance simply being $621 billion lower as of today. Next, I compound this present value forward to the year 2040 at a 5.2% interest rate, which is closer to the longer-term rates used in CBO's August 2008 Social Security update. This produces a value as of 2040 of $2.99 trillion. This shows the rough lost value to the trust at the point in which the fund is near exhaustion. In CBO's projections, the program is running annual nominal deficits of around $550 billion at that point (that's around $300 billion in today's dollars, for anyone interested). Now, I simply divide $2.99 trillion by $550 billion, which gives me a value of 5.45. This indicates that the lost income to the trust fund today is worth around five and one half years of solvency in the 2040s. The Social Security Trustees currently project the program will become insolvent in the year 2041, so the current recession could push that insolvency date forward to around 2036. Bear in mind that these numbers are approximate – you wouldn't want to do brain surgery this way. We will know more when the next Trustees Report is released. Moreover, lower wages today due to the recession can lead to lower promised benefits in the future, although I suspect the offset won't be on anything close to a one-to-one basis. (Losing a year of earnings due to unemployment would reduce benefits only if that year were among the worker's highest 35 and if he doesn't make it up by extending his work life later. In addition, if unemployment is concentrated among low earners, their benefits may become more progressive and partially make up for any losses.) In any event, though, this gives a rough feeling for the scale of the effects of the recession on long-term Social Security financing.

Even as of 2018, cash flow is almost $50 billion per year lower than was previously projected. I'm assuming this difference declines to zero within 10 years following 2018, although it's possible that the effect is permanent.