FactCheck.org has a new brief on a number of advertisements on Social Security being run in Congressional races. Here's the short story: Democrats celebrated Halloween early this year, trying to spook voters with the political boogeyman of risking Social Security in the stock market. Since October 1, we have found 58 ads from Democrats and their allies attacking their Republican House and Senate opponents on the issue. They mislead in several ways: Click here to read the full article.

Friday, October 31, 2008

FactCheck: Dems Mislead on Social Security Plans

The Economist on Social Security Reform

The Economist magazine has a nice report on the candidates' plans to fix Social Security and the general political dynamic surrounding reform. Worth a read.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

CRFB: Guide to Social Security: The 2008 Presidential Election

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget released a very useful paper summarizing the presidential candidates' views on Social Security reform and giving a menu of options available to them to make the program sustainable for the long term. It's definitely worth checking out. Click here to take a look.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Autumn newsletter from Michigan Retirement Research Center

The Michigan RRC has released its autumn newsletter, updating on new papers, the August RRC conference in Washington, and interviews with MRRC researchers. One interview in particular is well worth reading since it defies current conventional wisdom about Americans' level of preparation for retirement. John Karl Scholz and Ananth Seshadri are economists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who have written a number of excellent papers on Americans' retirement savings. They conclude – contrary to most press reports – that a strong majority of Americans are actually doing pretty well in terms of their retirement savings. Current retirees are overwhelmingly well-prepared, and even younger Americans – who we often assume to be doing next to nothing to prepare for retirement – are doing much better than most people would expect. The Scholz-Seshadri interview is well worth reading. If you're interested in reading their latest paper, here's a link.

Marmor and Mashaw: “Shoring up Social Security”

Ted Marmor and Jerry Mashaw are professors at Yale University and members of the National Academy of Social Insurance (Mashaw is currently on NASI's board, while Marmow served from 1986-1996). Together they write in today's Philadelphia Inquirer on the presidential candidate's views regarding reform: For the near term, the Social Security trust fund is an island in a sea of budgetary red ink. But, bombarded by talk of a crisis in Social Security financing, many Americans harbor the image of a program on the verge of collapse. Trustees expect the fund to have a $196 billion surplus in 2008, and continued surpluses are projected for the next 18 years. Reserves are expected to grow to more than $5.5 trillion by 2026. So what's the problem? Beginning in 2017, tax revenues flowing into the fund are projected to fall below expenditures. If the trustees' projections are correct and if no changes are made, reserves will be depleted by 2041. Thereafter, Social Security taxes would cover only about 78 percent of benefits due. We should be clear that these are projections, not predictions. Some analysts think they are too gloomy, others too sunny. But when a program supports so many U.S. families, it is prudent to try to secure its future. What have the presidential candidates told us about their plans for keeping Social Security's promises? Not very much. John McCain's position is difficult to pin down. He has expressed antipathy toward the program, calling it a disgrace at one point. His Web site suggests he is still committed to President Bush's plan to "privatize" it, at least partly. On the campaign trail, however, McCain has tried to distinguish privatization from Social Security's long-term financing needs. He could hardly do otherwise. Diverting some Social Security taxes to private, risk-bearing accounts would make the program's long-term financial picture worse, not better. At times, McCain has seemed to promote delegating the Social Security-financing issue to a bipartisan commission. That may well be a good idea. But it provides no information on where McCain really stands on shoring up the program. There are only three ways to do that: Increase tax revenues, decrease benefits, or increase the returns on the Social Security trust fund. The balance among those is what the political struggle over Social Security financing is about. Barack Obama, unlike McCain, has strongly supported Social Security in its current form and promised to maintain benefit levels for future retirees. He says he would shore up the program's finances by levying Social Security taxes on incomes above $250,000. Today, Social Security taxes are not collected on income above $102,000. It's not clear whether Obama's plan would actually fix Social Security, but it is consistent with his promise not to levy new taxes on middle-income Americans. This may be politically astute for this election year, but it is politically dangerous for the program. Social Security has remained immensely popular with U.S. voters largely because it combines two visions of fairness. Benefits are progressive: Lower-wage workers get larger retirement benefits than higher-wage workers in relation to their contributions. But it's not simply a welfare program: The more a worker pays into it, the higher that worker's benefits. The Obama proposal breaks the connection between taxes paid and benefits received. Benefits still would be based on taxes paid on incomes up to $102,000. But retirees would not get additional benefits for the taxes they paid on income above $250,000. Demanding increased taxes without increased benefits is not prudent for maintaining political support for Social Security. It damages the program's long-standing image as earned rather than handed out. Unfortunately, in the heat of this election campaign, one of the nation's most important and popular programs is not being treated seriously. McCain's only concrete proposal is standard Republican dogma: Whatever the problem, privatization is the solution. Obama responds with a standard Democratic nostrum: When in fiscal trouble, soak the rich. The U.S. electorate deserves better. Serious people have made many sensible proposals for safeguarding Social Security's long-term financing. Perhaps, after the election is over, we will get around to discussing some of them.

Monday, October 27, 2008

New paper: “The True Cost of Social Security”

A new paper by Alexander W. Blocker (Boston University), Laurence J. Kotlikoff (Boston University) and Stephen A. Ross (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) attempts to assign a market value to Social Security's long-term unfunded obligations. "The True Cost of Social Security" treats the Social Security program as a financial asset with certain unique characteristics, and then uses modern finance theory to place a value on the promises made under that program. Here's the summary: Implicit government obligations represent the lion's share of government liabilities in the U.S. and many other countries. Yet these liabilities are rarely measured, let alone properly adjusted for their risk. This paper shows, by example, how modern asset pricing can be used to value implicit fiscal debts taking into account their risk properties. The example is the U.S. Social Security System's net liability to working-age Americans. Marking this debt to market makes a big difference; its market value is 23 percent larger than the Social Security trustees' valuation method suggests. In other words, the true value of the long-term Social Security shortfall could be significantly larger than we currently suppose. I may have touched on this issue in discussion of the report of the 2007 Technical Panel on Assumptions and Methods. The panel's report, which came out several months ago, cited a paper by John Geanakoplos and Stephen Zeldes which attempted a similar exercise to the Blocker, Kotlikoff, Ross paper. However, Geanakoplos and Zeldes concluded that, using market pricing, Social Security's long term deficit was around 25 percent smaller than the Trustees project. In other words, both papers utilize more sophisticated analytical techniques but come to precisely opposite conclusions. My issue with the Tech Panel's report was that it recommended adopting the Geanakplos-Zeldes approach in the Trustees Report: The Panel recommends that the Trustees consider adopting risk-adjusted discount rates for computations that involve discounting. As well as making the measures more accurate theoretically, the use of higher discount weights has the salutary effect of reducing the sensitivity of the results to the more distant, and more uncertain, cash flows. This, I thought, was premature given that the Geanakplos-Zeldes paper hadn't even yet been published, and the Blocker, Kotlikoff, Ross paper makes me think even more that these methods aren't quite ready for prime time. The Trustees Report currently contains some new approaches that it didn't use 10 or so years ago – stochastic forecasting, the infinite horizon actuarial balance, and others – but these methods were thoroughly used in academic and policy research before being applied in the Trustees Report. I suspect that market pricing of Social Security liabilities should go through a similar process before going in the Trustees Report.

Samuelson: “Young Voters -- Get Mad”

A few days old but still worth linking to, Robert Sameulson writes on the intergenerational conflict implicit in entitlement reform. You're being played for chumps. Barack Obama and John McCain want your votes, but they're ignoring your interests. You face a heavily mortgaged future. You'll pay Social Security and Medicare for aging baby boomers. The needed federal tax increase might total 50 percent over the next 25 years. Plus there's the expense of decaying infrastructure -- roads, bridges, water pipes. Pension and health costs for state and local workers have doubtlessly been underestimated. All this will squeeze other crucial government services: education, defense, police. Guess what. You're not hearing much of this in the campaign. One reason, frankly, is that you don't seem to care. Obama's your favorite candidate (by a 64 percent to 33 percent margin among 18- to 29-year-olds, according to the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll). But he's outsourced his position on these issues to the AARP, the 40-million-member group for Americans 50 and over. I agree with Samuelson that population aging implies tough decisions, and the welfare of different generations will depend on what those decisions are and when they are made. We should attempt to smooth costs and benefits evenly over generations, rather than letting some groups do well and others poorly. That said, as I've argued elsewhere, I don't believe the underlying Social Security problem is one of greedy Baby Boomers or anything like that. (That might be the problem with Medicare, but that's another story…) Most current and future retirees under Social Security more than paid for their benefits, meaning that their contributions – compounded at the interest rate earned by the trust fund – are enough to finance their benefits. The problem is an inherited "legacy debt" from prior generations, who received much more than they paid for and left the program underfinanced for the long-term. This means a) that there's nothing we can do about the Social Security deficit except suck it and figure out tax increases and/or benefit cuts; but also b) that there isn't a huge moral conflict between young and old, such that one is the victim and the other the villain. So young voters should get mad – at politicians who refuse to take on the tough but important issues. But they shouldn't necessarily get mad at older voters.

Marketwatch: “Fiscal crisis not a death knell for privatizing Social Security”

Christopher Plummer writes for Marketwatch that the current financial crisis has not put an end to the talk of personal accounts for Social Security. A variety of analysts are quoted, both pro and con, but all seem to agree that the argument over Social Security and personal accounts isn't finished. I've made a seemingly similar argument here, that current market returns don't imply that personal accounts would have been a bad deal for most workers. In fact, despite recent down turns, workers holding accounts over a full working lifetime would have all done very well. That said, I don't think market returns have been the biggest obstacle to implementing Social Security accounts. The "transition costs" associated with accounts are a bigger burden; if they're paid, they imply a "double tax" on transition generations. If they're not paid, then accounts really amount to a shuffling of paper assets around, but no real change in the pot of retirement income available for future seniors. One unrelated point: the Economic Policy Institute's Ross Eisenbrey, who opposes personal accounts for Social Security, says: "Nobel Prize winners in economics have admitted mismanaging their own 401(k) accounts; the third of retirees whose only income is Social Security can't afford that risk." Ok. But what exactly were the mistakes those Nobel Prize winners made? Harry Markowitz, developer of modern portfolio theory which shows how diversification can boost returns without increasing risk, said, "In retrospect, it would have been better to have been more in stocks when I was younger." Another poor investor was 2001 winner George A. Akerlof, who kept all his retirement savings in a money market fund. "I know it's utterly stupid," Akerloff said. The point here is that the main mistake these Nobel Prize winning economists made was not investing enough in equities. Yet Eisenbrey's preferred policy would ensure that low-income workers, who have no retirement savings other than Social Security, would make the same mistake. Thanks, Ross!

Friday, October 24, 2008

New article: Obama Wants Social Security to Be a Welfare Plan

I have a piece in today's Wall Street Journal that builds on posts and comments here and here. Obama Wants Social Security to Be a Welfare Plan His tax credit amounts to a radical change in the system. Imagine this: Barack Obama proposes a Social Security payroll tax cut for low earners. Workers earning up to $8,000 per year would receive back the full 6.2% employee share of the 12.4% total payroll tax, up to $500 per year. Workers earning over $8,000 would receive $500 each, with this credit phasing out for individuals earning between $75,000 and $85,000. This tax cut would make an already progressive Social Security program even more redistributive. Under current law, a very low earner receives an inflation-adjusted return on his Social Security taxes of around 4%. That's a good return, given that government bonds are projected to return less than 3% above inflation. A high-earning worker, on the other hand, receives only around a 1.5% rate of return. Under Sen. Obama's proposal, returns for very low earners would rise to around 6% above inflation -- about the same return as on stocks, except with none of the risk. Compounded over a lifetime's contributions, the difference in the "deal" offered to workers of different earnings levels would be extreme. While Social Security has always been progressive, many would say this plan goes too far and risks turning Social Security into a "welfare program." Low earners receive more in benefits than they pay in taxes -- meaning their "net tax" is already negative -- and Mr. Obama's plan would increase net subsidies from the program. Moreover, this payroll tax cut plan would reduce Social Security's tax revenues by around $710 billion over the next 10 years. If made permanent, the Obama tax cut would increase Social Security's long-term deficit by almost 60% and push the program into insolvency in 2034, versus 2041 under current projections. To fill the hole in Social Security's finances, Mr. Obama would increase income taxes on high earners and pour that money into Social Security. This would be the first time that income tax revenues have been used to finance Social Security, which has always relied on its own dedicated payroll tax to differentiate itself from other government programs. Filling the gap with higher taxes on high earners would further increase Social Security's progressivity, pushing it closer toward a welfare-program approach. Now, you haven't heard Mr. Obama describe anything like this plan. If you had, it's likely you wouldn't support it. But it's almost exactly what his headline "tax cut" would do. The Obama campaign took the idea described above and made it much more complicated. Under the plan, which he claims would cut taxes for 95% of Americans, provides an income tax credit worth 6.2% of earnings up to $8,000, for a maximum credit of $500 per worker or $1,000 per couple. The 6.2% figure is important, because it matches the employee share of the Social Security payroll tax. Because around a third of Americans currently pay no income taxes -- a fraction that would rise to almost half under Mr. Obama's plan, according to the Tax Policy Center -- Mr. Obama's tax credits would be refundable, meaning you could collect the credit even if you paid no income taxes. While Mr. Obama calls his plan "Making Work Pay," under standard economic assumptions his plan would actually discourage work for anyone earning over $8,000 per year. The tax credit itself would increase workers' take-home pay, an "income effect" that reduces incentives to work. Moreover, for workers in the $75,000 to $85,000 income range, where the tax credit is phased out at five cents for each dollar of additional income, this would add five percentage points to their marginal tax rate. So Mr. Obama has in essence proposed cutting Social Security taxes for low earners, which would shift the system toward a "welfare" approach and sharply increase its long-term deficit. To fill the funding gap, he will raise taxes on high earners and funnel the money into Social Security, making the system even more progressive and breaking a long tradition against funding Social Security with income taxes. The complex way in which Mr. Obama structures and describes his plan would make it harder to administer than a straight payroll tax cut. But it is also more difficult for the typical American to understand. This may explain why he chose complexity over clarity.

Thursday, October 23, 2008

New paper: Alternate Measures of Replacement Rates for Social Security Benefits and Retirement Income

I have a new paper out in the Social Security Bulletin co-authored with Glenn Springstead, of the Office of Retirement and Disability Policy at SSA. The paper is entitled "Alternate Measures of Replacement Rates for Social Security Benefits and Retirement Income" and looks at the ways in which we measure retirement income adequacy. Here's the summary, followed by some notes: Discussions of retirement planning and Social Security policy often focus on replacement rates, which represent retirement income or Social Security benefits relative to pre-retirement earnings. Replacement rates are a rule of thumb designed to simplify the process of smoothing consumption over individuals' lifetimes. Despite their widespread use, however, there is no common means of measuring replacement rates. Various measures of pre-retirement earnings mean that the denominators used in replacement rate calculations are often inconsistent and can lead to confusion. Whether a given replacement rate represents an adequate retirement income depends on whether the denominator in the replacement rate calculation is an appropriate measure of preretirement earnings. This article illustrates replacement rates using four measures of preretirement earnings: final earnings; the constant income payable from the present value (PV) of lifetime earnings (PV payment); the wage-indexed average of all earnings prior to claiming Social Security benefits; and the inflation-adjusted average of all earnings prior to claiming Social Security benefits (consumer price index (CPI) average). The article then measures replacement rates against a sample of the Social Security beneficiary population using the Social Security Administration's Modeling Income in the Near Term (MINT) microsimulation model. Replacement rates are shown based on Social Security benefits alone, to indicate the adequacy of the current benefit structure, as well as on total retirement income including defined benefit pensions and financial assets, to indicate total preparedness for retirement. The results show that replacement rates can vary considerably based on the definition of preretirement earnings used and whether replacement rates are measured on an individual or a shared basis. For current new retirees, replacement rates based on all sources of retirement income seem strong by most measures and are projected to remain so as these individuals age. For new retirees in 2040, replacement rates are projected to be lower, though still adequate on average based on most common benchmarks. Here's a quote from a SSA publication that motivated this paper for me: "Most financial advisors say you'll need about 70 percent of your pre-retirement earnings to comfortably maintain your pre-retirement standard of living. Under current law, if you have average earnings, your Social Security retirement benefits will replace only about 40 percent." Here's the problem: financial advisors measure replacement rates by dividing your retirement income by your income immediately preceding retirement; say, income at age 65 divided by income at age 64. Social Security defines the replacement rate as the Social Security benefit divided by the wage-indexed average of your lifetime earnings. These are two different animals, so comparing Social Security's 40 percent average replacement rate to the 70 percent recommended replacement rate is apples and oranges. In the paper we discuss the pros and cons of various ways of defining replacement rates. In the process, though, we also use the Social Security Administration's MINT microsimulation model to measure Social Security and total retirement income replacement rates for current retirees. This is cool because MINT is the best, most detailed model available for running these kinds of numbers. The table below shows the distribution of Social Security replacement rates compared to various definitions of pre-retirement income. Table 4: Median Shared Benefit Replacement Rates for Retired Beneficiaries age 64-66 in 2005 Lifetime earnings quintile Lowest 2nd 3rd 4th Highest Final Earnings 137% 77% 69% 53% 42% PV Payment 62% 47% 42% 40% 36% AIME 70% 52% 45% 41% 36% CPI Average 82% 60% 53% 48% 42% Source: MINT model, authors' calculations; N = 3,604. Numerator is shared benefit; denominator is shared value as defined in the text. Table 5: Lifetime earnings quintile Lowest 2nd 3rd 4th Highest Final Earnings 381% 210% 185% 161% 143% PV Payment 160% 111% 98% 108% 115% AIME 176% 120% 106% 112% 112% CPI Average 204% 141% 124% 130% 130% Source: Authors' calculations, MINT model. Numerator is shared total retirement income; denominator is as defined in the text. This last table is interesting, because it provides some perspective for those who are afraid that we're facing a crisis in retirement income. For instance, the median household has a total retirement income equal to 124 percent of their inflation-adjusted average income during their working years. (This may or may not be the best replacement rate measure to use, but it's easily understandable.) We find relatively few households with very low replacement rates, indicating that concerns over retirement income – while not invalid – may be overstated. There are a few other interesting results as well, including the finding that – contrary to some views – replacement rates don't tend to decline as people age. Anyway, I hope folks will read this and find it interesting.

The next table shows replacement rates for total retirement income, which includes Social Security, pensions, asset income, earnings and co-resident income.

Median Shared Total Retirement Income Replacement Rates for Retired Beneficiaries age 64-66 in 2005

Argentina attempts to nationalize personal accounts system; workers object

Joaquin Cottani at the RGE Monitor reports on some interesting pension developments in Argentina that shed some light on Social Security policy in the U.S. Argentina, like most Latin American countries, bases its pension program on personal retirement accounts. Individuals contribute to their accounts during their working years, then at retirement use the account balance to purchase an annuity paying them a monthly benefit for life. But the government of Argentina, led by President Cristina Kirchner, is attempting to end their personal accounts system. Is this a response to public pressure from Argentines who want the supposedly greater security and lower risk of a government-provided benefit? Not at all. In fact, it's a scheme by the Argentine government to paper over its current budget deficit and has parallels to what has gone on in the U.S. Social Security system for the past 25 years. In the Argentine personal accounts system, workers pay contributions to their account fund, not to the government-run pay-as-you-go program. Argentina's government, however, is running a budget deficit and is setting their eyes on workers' account contributions. If workers are forced back into the pay-as-you-go system, the government gets access to their contributions which can be used to cover up deficits elsewhere in the government. Of course, the government is also obligated to pay these workers retirement benefits in the future – but these "implicit debts" aren't counted on the government's balance sheet , as they aren't counted on the U.S. balance sheet, and so the Argentine government effectively ignores them. The Argentine government first tried to bribe workers back into the pay-as-you-go system by promising increased benefits later. This shows how eager the government is to get its hands on the workers' cash today. But few workers took the deal, and so now President Kirchner is apparently pushing legislation that would force Argentinean workers back into the pay-as-you-go program. How does this relate to Social Security in the U.S., in particular the budgetary debate between the current pay-as-you-go system and proposed reforms using personal accounts? Since the last reforms in the mid-1980s, Social Security has been running payroll tax surpluses – collecting more in taxes than is needed to pay benefits. This surplus in Social Security helps cover up deficits in the rest of the budget. In fact, many analysts think that the Social Security surpluses encourage deficits in the rest of the budget. Moreover, when the rest of the budget borrows from Social Security, this borrowing isn't counted as part of the publicly-held national debt, the debt measure that most people focus on. In short, if we didn't have the Social Security surplus, both the budget deficit and the government debt would look a lot bigger than they do, and folks in Congress would be feeling more heat to do something about it. This is the situation that Argentina's President Kirchner is trying to restore. Now, what happens if we allow people to invest part of their Social Security taxes in a personal account? Well, that immediately erases the Social Security surplus, which means that the budget deficit and the debt would start to look bigger. Now, some on the left blame this increased deficit/debt on the accounts, when in fact all the accounts do is reveal a budget shortfall that already existed. Moreover, to the degree that larger accounts create short term deficits, they also create assets that help pay Social Security benefits in the future. In other words, this claimed increase in the debt is mostly a function of government accounting, not of reality. Update: Here's an editorial from the Wall Street Journal on the same topic.

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

New paper: Are Retirement Savings Too Exposed to Market Risk?

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College has release a new issue brief by Alicia H. Munnell and Dan Muldoon entitled "Are Retirement Savings Too Exposed to Market Risk?" which looks at how recent market declines have affected retirement savings portfolios. The stock market, as measured by the broad-based Wilshire 5000, declined by 42 percent between its peak in October 9, 2007 and October 9, 2008. Over that one-year period, the value of equities in pension plans and household portfolios fell by $7.4 trillion. Of that $7.4 trillion decline, $2.0 trillion occurred in 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), $1.9 trillion in public and private defined benefit plans, and $3.6 trillion in household non-pension assets. This brief documents where the declines occurred. This information is interesting and important in its own right. But the declines also highlight the fragility of our emerging pension arrangements. Today the declines were divided equally between defined benefit and defined contribution plans, but in the future individuals will bear the full brunt of market turmoil as the shift to 401(k)s continues. Much of the reform discussion regarding private sector employer-sponsored pensions has focused on extending coverage. But the current financial tsunami also underlines the need to construct arrangements where the full market risk does not fall on pension participants. Click here to read the full document.

Rockeymore: “Don't save Social Security by raising retirement age”

Maya Rockeymore, president and CEO of Global Policy Solutions and an adjunct professor at American University, writes in the Houston Chronicle that an increasing longevity gap between rich and poor means we shouldn't try to fix Social Security's funding problems by raising the retirement age. The normal retirement age is currently 66, and rising under current law to 67 by the early 2020s, and many analysts argue it should rise further as life spans continue to increase. Rockeymore writes: Some policy experts argue that increasing the retirement age is a sure-fire way to extend the solvency of Social Security. But lawmakers overlook how this option would unfairly disadvantage people with shorter life expectancies. Declining life expectancies for vulnerable populations such as low-income and lesser educated individuals means that increasing the retirement age would have the unfair effect of using their lifetime payroll tax contributions to subsidize the retirements of people who live longer. Often, these people are wealthier, better educated and white. Rockeymore is correct that, while there has always been a longevity gap between rich and poor, this difference appears to be widening. By itself, this would make Social Security less progressive, since high earners would tend to collect benefits longer than low earners. The CBO put out a nice paper on this subject back in April. However, it's not clear that increasing the normal retirement age would exacerbate this effect. Remember that an increase in the normal retirement age is nothing other than a benefit cut. If the retirement age rises by a year, that means that everyone will receive around 7 percent lower benefits than they otherwise would have. Raising the retirement age is no different than an across the board 7 percent benefit cut. An across the board benefit cut wouldn't disproportionately hurt low earners or those with short life spans; everyone – rich and poor, short or long-lived – will receive 7 percent less than they otherwise would have. On the other hand, raising the early retirement age of 62 would disproportionately hurt those with short life spans, since more of them would die before being able to claim any benefits. This simple spreadsheet shows that that raising the normal retirement age would reduce everyone's benefits equally, even if the rich live longer than the poor, while raising the early retirement age would tend to hit the poor/short-lived more than others. I did some more detailed modeling here. So I think we've established that Rockeymore's basic underlying premise isn't really correct. Raising the retirement age doesn't have a hugely disproportionate effect on low earners or short-lived individuals. However, she goes on to make a policy recommendation that I think is also working looking at: There are fairer policy options that would achieve the solvency goal. For example, Sen. Barack Obama proposes to increase Social Security's cap on taxable earnings. True, this taxes higher earners without giving them more monetary benefits. But that is neither a policy reversal nor a detour from the shared national values that make Social Security the most popular law in history. Rather, it returns Social Security to its intended progressive course, correcting the unfair and unintended regressive impact that widening life expectancies are creating for women in some areas of the country and for low-income, less-educated and minority workers. First, it is true that a widening longevity gap would make Social Security less progressive and that applying a new payroll tax on people earning over $250,000 would make the system more progressive. I have no idea (and I suspect neither does Rockeymore) whether the increased progressivity from the new tax would be the same size as the reduced progressivity from the widening longevity gap. My guess is that the tax would be significantly more progressive than the longevity gap is regressive, but we'd have to run some numbers on that. The point here is that you want things to be at least roughly proportional. Second, Rockeymore says that applying a new tax on workers earning $250,000 without paying them any extra benefits "is neither a policy reversal nor a detour from the shared national values that make Social Security the most popular law in history." Huh? Let's see: Social Security has never levied taxes above the payroll tax ceiling (currently $102,000), and it has never levied taxes without paying additional benefits in return. So to me it seems to be exactly a policy reversal from how the program was founded and how it has continued to run since the 1930s. If we wish to control for the effects of a widening longevity gap there are some simple ways to do it. For instance, Social Security current replaces a progressive proportion of workers' pre-retirement earnings. In 2008, the benefit at the full retirement age equals: (a) 90 percent of the first $744 of his/her average indexed monthly earnings, plus (b) 32 percent of his/her average indexed monthly earnings over $744 and through $4,483, plus (c) 15 percent of his/her average indexed monthly earnings over $4,483. If the richer are living increasingly long lives relative to the poor, all we need to do is tweak these parameters to restore whatever level of progressivity we desire. For instance, we might increase the 90 percent replacement factor to slightly raise benefits for low earners, while slightly reducing the 15 percent replacement factor that applies mostly to high earners' benefits. This doesn't demand anything radical.

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

WSJ: Obama Talks Nonsense on Tax Cuts

Columnist Bill McGurn writes for the Wall Street Journal: Now we know: 95% of Americans will get a "tax cut" under Barack Obama after all. Those on the receiving end of a check will include the estimated 44% of Americans who will owe no federal income taxes under his plan. In most parts of America, getting money back on taxes you haven't paid sounds a lot like welfare. Ah, say the Obama people, you forget: Even those who pay no income taxes pay payroll taxes for Social Security. Under the Obama plan, they say, these Americans would get an income tax credit up to $500 based on what they are paying into Social Security. Just two little questions: If people are going to get a tax refund based on what they pay into Social Security, then we're not really talking about income tax relief, are we? And if what we're really talking about is payroll tax relief, doesn't that mean billions of dollars in lost revenue for a Social Security trust fund that is already badly underfinanced? Austan Goolsbee, the University of Chicago economic professor who serves as one of Sen. Obama's top advisers, discussed these issues during a recent appearance on Fox News. There he stated that the answer to the first question is that these Americans are getting an income tax rebate. And the answer to the second is that the money would not actually come out of Social Security. "You can't just cut the payroll tax because that's what funds Social Security," Mr. Goolsbee told Fox's Shepard Smith. "So if you tried to do that, you would undermine the Social Security Trust Fund." Now, if you have been following this so far, you have learned that people who pay no income tax will get an income tax refund. You have also learned that this check will represent relief for the payroll taxes these people do pay. And you have been assured that this rebate check won't actually come out of payroll taxes, lest we harm Social Security. You have to admire the audacity. With one touch of the Obama magic, what otherwise would be described as taking money from Peter to pay Paul is now transformed into Paul's tax relief. Where a tax cut for payroll taxes paid will not in fact come from payroll taxes. And where all these plans come together under the rhetorical umbrella of "Making Work Pay." Not everyone is persuaded. Andrew Biggs is a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a former Social Security Administration official who has written a great deal about Mr. Obama's plans on his blog (AndrewGBiggs.blogspot.com). He notes that to understand the unintended consequences, it helps to remember that while people at the bottom pay a higher percentage of their income in payroll taxes, they are accruing benefits in excess of what they pay in. "It's interesting that Mr. Obama calls his plan 'Making Work Pay,'" says Mr. Biggs, "because the incentives are just the opposite. By expanding benefits for people whose benefits exceed their taxes, you're increasing their disincentive for work. And you're doing the same at the top of the income scale, where you are raising their taxes so you can distribute the revenue to others." Even more interesting is what Mr. Obama's "tax cuts" do to Social Security financing. As Mr. Biggs notes, had Mr. Obama proposed to pay for payroll tax relief out of, well, payroll taxes, his plan would never have a chance in Congress. Most members would look at a plan that defunded a trust fund that seniors are counting on for their retirement as political suicide. And that leads us to the heart of this problem. If the government is going to give tax cuts to 44% of American based on their Social Security taxes -- without actually refunding to them the money they are paying into Social Security -- Mr. Obama will have to get the funds elsewhere. And this is where "general revenues" turns out to be a more agreeable way of saying "Other People's Money." When asked about his priorities during the second presidential debate, Mr. Obama said that reform of programs like Social Security would have to go on the back burner for two years or so. "We're not going to solve Social Security and Medicare unless we understand the rest of our tax policies," he said. The senator is right. But you have to read the fine print of his tax cuts to know why.

Monday, October 20, 2008

Obama: Tax cuts or welfare?

There's been a fair amount of ink spilled on whether Sen. Obama's claim that he would give tax cuts to 95 percent of Americans is legit. The key point is whether a transfer made to an individual who does not currently pay income taxes can be counted as a "tax cut." The core component of Sen. Obama's tax cut plan is called "Making Work Pay." I've discussed it elsewhere, but the key claim is that it provides a $500 refundable income tax credit for each worker, for a maximum of $1000 per couple. The Tax Policy Center estimates its 10-year cost at $710 billion, so it's obviously a big-ticket item in Obama's tax agenda. So here's the question: how should we categorize these policies? The Tax Foundation reports that 33 percent of filers currently pay no net income taxes, which means that 67 percent of filers do. Since 95 percent is larger than 67 percent, it's seemingly hard for Sen. Obama to argue that 95 of Americans will receive a tax cut when only 67 percent are paying taxes in the first place. The Wall Street Journal editorial page relies on this argument in calling Obama's claims an "illusion." But note that the references above are to the percentage of Americans paying income taxes. Most or all of the tax filers who do not pay income taxes do pay payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare. Obama's plan is clearly designed to compensate workers for the employee share of the Social Security payroll tax, which is 6.2 percent of all wages under $102,000. Under Obama's plan, workers would receive a refundable tax credit equal to 6.2% of wages up to $8,000, with a maximum credit of $500 per worker and $1,000 per couple. In effect, workers earning $8,000 would receive a full rebate of their Social Security payroll taxes while those earning more would receive a partial rebate. Obama economic advisor Jason Furman says, "Senator Obama believes that the tens of millions of families working hard and paying payroll taxes do not think that tax cuts are a form of 'welfare' or 'redistribution' - they think it is only fair to reward work." Having laid that out, a few points seem relevant:

Read more!

Saturday, October 18, 2008

AP: Candidates' Social Security plans lack details

The Associated Press writes on the Sens. Obama and McCain's plans for Social Security – or lack thereof. Barack Obama wants to raise taxes on high-income workers to ease Social Security's looming cash crunch. John McCain favors voluntary private accounts for younger workers, saying they can't count on the same government benefits as today's retirees. Beyond those generalities — and a shared opposition to an increase in the retirement age — the two presidential rivals are long on commitment and short on specifics when it comes to the government's huge retirement income program. Click here to read the full story.

Friday, October 17, 2008

New paper: “The Impact of Inflation on Social Security Benefits”

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College released a new issue brief by Center director Alicia Munnell and research associate Dan Muldoon, entitled "The Impact of Inflation on Social Security Benefits," well-timed based on yesterday's announcement of a 5.8 percent annual Cost of Living Adjustment for benefits. Today, the Social Security Administration announced that benefits payable in December 2008 would be increased 5.8 percent beginning January 1, 2009. This cost-of-living-adjustment (COLA) – the largest in 26 years – is an important reminder that keeping pace with inflation is one of the attributes that makes Social Security benefits such a unique source of income. (The other is that the payments continue for life.) Higher inflation raises two other issues, however, that diminish the impact of the COLA. The first issue pertains to Medicare Part B premiums, which are deducted automatically from Social Security benefits. To the extent that premium costs rise faster than the COLA, the net benefit will not keep pace with inflation. Historically, premiums have gone up much faster than the COLA, although this year is an exception as premiums for 2009 will be unchanged from their current level. The second issue pertains to taxation under the personal income tax. Because the thresholds ($25,000 for single taxpayers and $32,000 for joint returns) above which taxes are levied are not adjusted for wage growth or even for inflation, rising benefit levels mean that taxation reaches further and further down the income distribution. Click here to read the whole brief.

New article: “What does the turbulent stock market tell us about Social Security personal accounts?”

I've written about this before, but I have an article today on National Review Online that looks at how Social Security personal accounts would have fared under today's market conditions. The motivation behind the piece was a question from Sen. Obama, asking how you would have felt had you invested part of your Social Security taxes in an account. Presumably it was a rhetorical question, but I took it seriously and was surprised at what I found: assuming a full career with a personal account, even a person retiring today would have increased their total Social Security benefits. A note on titles: last week I had a piece with Kent Smetters in the Wall Street Journal, which was given the title "The Rich Pay Their Fair Share"; what we actually argued was that you couldn't even judge whether the rich pay their fair share given the type of information on tax policy generally reported in the press. The title here – "Still a Good Idea" – is a bit similar: my analysis doesn't prove that accounts are a good idea, but it disproves one argument for why they'd be a bad idea. So I guess you could have called it "Personal accounts: No worse an idea than before" or something along those lines. (My career prospects as a headline writer are probably very limited – although I always thought that "Headless body in Topless Bar" was a classic.) In any case, here's the piece followed by an added chart. Still a Good Idea The recent financial crisis and ensuing stock-market gyrations have drawn renewed attention to Social Security reform, in particular proposals to establish personal retirement accounts investing in stocks and bonds. Sensing a political opening, Sen. Barack Obama tells campaign audiences, "If my opponent had his way millions of Americans would have had their Social Security tied to stock market this week. Millions would have watched as the market tumbled and their nest egg disappeared before their eyes… Imagine if you had some of your Social Security money in the stock market right now. How would you be feeling about the prospects for your retirement?" Here's a chart comparing the real internal rates of return on personal accounts holding a life cycle fund versus an all-bond account, for individuals retiring from 1915 through today. I have a longer paper (hopefully) coming out soon from AEI that will look into this issue in more detail and show why my results differ from those of Robert Shiller. When that comes out I'll post the data and calculations showing where the numbers came from.

What does the turbulent stock market tell us about Social Security personal accounts?

By Andrew G. Biggs

Well, let's imagine that: if Social Security included personal accounts, how would an American retiring today have fared? Despite recent market downturns — the S&P 500 index is down 24 percent for the year as this article is written — the answer is not at all what you would think.

Consider a simple personal account plan similar to those introduced in Congress. Workers could voluntarily invest 4 percentage points of the 12.4 percent Social Security payroll tax in a "life cycle portfolio," which would shift from holding 85 percent stocks through age 29 to only 15 percent stocks by age 55. At retirement, the account balance would be converted to pay a monthly annuity benefit.

However, workers who chose to divert a portion of their payroll taxes to a personal account would also receive a reduced traditional benefit. Traditional Social Security benefits for account holders would be reduced by the amount they contributed to the account, plus interest at the rate earned by government bonds held in the Social Security trust fund. This would keep the current system's finances roughly neutral.

Account holders' total Social Security benefits would increase if their account returned more than the interest rate on government bonds. This makes analyzing how account holders would have fared a relatively simple task.

Using historical stock and bond returns since 1965, I simulated an individual who held a personal account his entire career and retired in September 2008. A typical retiree in 2008 would be entitled to a traditional Social Security benefit of around $15,700 per year. For workers who chose personal accounts, this traditional benefit would be reduced by around $7,800. However, the worker's personal account balance of $161,500 would pay an annual annuity benefit of around $10,100. This $2,300 net benefit increase would raise total Social Security benefits by around 15 percent.

While today's retiree would have faced the subprime crisis and the tech bubble earlier in the decade, he also would have benefited from the bull markets of the 1980s and 1990s. The average return on his account — 4.9 percent above inflation — would more than compensate for a reduced traditional benefit.

While this is an isolated case, it is telling that the very example Sen. Obama uses to illustrate the dangers of personal accounts in fact refutes the point he is attempting to make. Even workers retiring today would have increased their Social Security benefits by choosing a personal account.

But we can go further. Using stock and bond data from 1871 through 2008 I simulated 95 separate cohorts of account holders retiring from 1915 through 2008. Despite the ups and downs of the stock market, every single group of retirees would have increased their benefits by investing in personal accounts. Total benefits would have increased by between 6 and 23 percent, with an average increase of 15 percent.

The point here isn't that stock investments are a free lunch. In an efficient market the higher returns paid to stocks are nothing more than compensation for their higher risk, and we don't know that future market returns will be as good as those in the past. But accounts do provide a valuable tool to prefund future retirement benefits and reduce cost burdens on tomorrow's workers. And these numbers put the lie to Sen. Obama's exaggerations of the risks of investing in the market.

— Andrew G. Biggs is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C.

Thursday, October 16, 2008

Obama advisor: “Ask high earners to pay more into Social Security”

Jason Furman, chief economic advisor to the Obama campaign, writes on Social Security in the DesMoines Register: Sen. Barack Obama is committed to protecting retirement security, strengthening seniors' health-care coverage and treating all seniors with a respect that dignifies their many contributions to our country. Obama is confident that we can come together to find a workable solution. He believes that one strong option to improve Social Security's long-term solvency is asking people who earn more than $250,000 to pay a little more into the system. But Obama will not raise the retirement age or reduce Social Security benefits. Ensuring the future solvency of the Medicare trust fund may be our toughest fiscal challenge. Forty-two million Americans currently rely on Medicare, and Obama is fundamentally committed to Medicare's long-term strength. Washington is broken, and it has failed to overcome the special interests and pass health-care reform that expands coverage and lower costs, which would keep Medicare strong and affordable for America's seniors. As president, Obama will reduce costs in the Medicare program by enacting reforms to lower the price of prescription drugs, end the subsidies for private insurers in the Medicare Advantage program and focus resources on prevention and effective chronic-disease management. Obama will also bring Democrats and Republicans together to provide every single American with affordable, available health care that reduces health-care costs by $2,500 per family. By investing in proven measures to improve the health of all Americans and reduce health-care costs across the economy, we can ensure that the Medicare program remains strong for future generations. All reasonable stuff, as far as it goes. But one question: If Sen. Obama wants to "ask" high earners to pay more, doesn't that imply they get the option to say "no"? I didn't think so… Ok, one other question: if Obama wants to apply a new tax to people earning over $250,000 -- which we know will fix at most around 16% of the 75-year deficit -- and if Obama has ruled out raising the retirement age or cutting benefits, what else is left? You guessed it: higher taxes on people earning less than $250,000. Even assuming Obama imposes a 4% tax on all earnings above $250,000 and pays no extra benefits -- a double first for Social Security -- the trust fund would remain solvent only around 3 extra years. The numbers just don't work -- mathematically, Obama can't keep his promise not to cut benefits or raise the retirement age unless he's got another source of tax income. A very big source.

He understands that the challenges facing Social Security and Medicare are very different. Despite the cries of privatization proponents, Social Security is not in crisis - it has a manageable cash-flow issue that we can ably solve over the upcoming years and decades.

Even more important, Obama strongly opposes the privatization schemes that George Bush championed; Americans' retirements should not be subject to the whims of the stock market. Social Security is one of the most successful government programs in our nation's history. As president, Obama will keep Social Security strong for future generations.

Obama is serious about his commitment to America's seniors: He will protect Social Security, strengthen Medicare and work to make sure Americans are able to enjoy a healthy, secure retirement.

Social Security reform on Fox Business

Michelle Plasari of Retire Safe and Ryan Lynch of Students for Saving Social Security discussed reform options on Fox Business channel yesterday.

Click here to go to RetireSafe.org and here to visit S4.

Read more!

Social Security COLA to be 5.8%

The Social Security Administration will today announce the 2008 Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) to benefits will be 5.8 percent, the highest in over two decades. This increase reflects higher consumer prices and is designed to maintain the purchasing power of Social Security benefits against the effects of inflation. Here's an informative report from Martin Crutsinger with the Associated Press. One related point I've been thinking about the past few days: as I understand current law, COLAs are applied only if the Consumer Price Index rises, but nominal benefits are not reduced if the CPI falls (i.e., if there is deflation rather than inflation). This effectively increases real benefit levels, since the purchasing power of constant nominal benefits would increase in the case of deflation. In essence, there's a 'ratchet effect' when deflation occurs. Now, deflation isn't very common, but it's far from unknown. If we assume a future inflation rate of 2.8 percent (as the Social Security Trustees do) and also assume the historical standard deviation of 2.9 percent, we can project that future CPI inflation will be negative around 16 percent of the time. (One reason deflation was uncommon historically is that the mean rate of CPI increase was higher, at 4.2 percent from 1960 through 2006.) In certain cases where deflation was relatively common, this could increase Social Security's deficit, since benefits would increase faster than the taxes used to finance them.

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Michigan RRC posts new draft papers

The University of Michigan Retirement Research Center, a part of the larger Retirement Research Consortium sponsored by the Social Security Administration, has released a number of draft papers.

Read more!

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

New paper: “Social Security: Who Wants Private Accounts?”

Although the polling data isn't current and support for accounts has dropped a lot, the analysis in this new paper by Michael S. Finke Preference for partial privatization of social security is explored using a 2004 sample of 7,565 young baby boomers. Two-thirds of the sample would choose partial privatization. While a greater proportion of higher-income, wealthier, and more educated respondents preferred private accounts, multivariate analysis reveals that intelligence has a stronger effect than socio-economic variables. An average of 43% would be invested in equities, but a surprising 35% would be invested in government bonds. Men and those with higher intelligence are more likely to prefer equities, while women prefer corporate bonds and the less educated, blacks, and respondents with children preferred government bonds. Click here to read the whole paper.

of Texas Tech and Swarn Chatterjee of the University of Georgia is very interesting. Using the raw data from a 2004 survey on Social Security personal accounts, they do a regression analysis on the factors that best predict support or opposition to accounts. Here's the synopsis:

New paper: “How Is the Economic Turmoil Affecting Older Americans?”

The Urban Institute has released a new paper by Richard W. Johnson, Mauricio Soto, and Sheila R. Zedlewski entitled "How Is the Economic Turmoil Affecting Older Americans?" The slumping stock market, falling housing prices, and weakening economy have serious repercussions for the 94 million Americans age 50 and older who are approaching retirement or already retired. Retirement accounts lost about 18 percent of their value over the past 12 months, and between January 2007 and May 2008, housing prices fell from 4 to 20 percent depending on where seniors live. Older Americans have little time to recoup the values of their homes, 401(k) plans, and individual retirement accounts—all important parts of their retirement nest eggs. More and more older Americans are working to bolster their retirement incomes, but the rising unemployment rate, now 6.1 percent, limits their prospects. This fact sheet examines the impact of the ongoing economic turmoil on retirement savings, home values, and retirement decisions. Click here to read the whole paper.

Time works against candidates on Social Security, Medicare fixes

David Lightman and Kevin G. Hall of McClatchy Newspapers report on how the presidential candidate's lack of attention to Social Security and Medicare can only mean delay in fixing them, which in turn increases the cost and difficulty of any reform. Social Security and Medicare long have been considered the nation's fiscal time bombs, and the ticking is getting louder. But presidential candidates Barack Obama and John McCain have no comprehensive plans to overhaul the systems, and are campaigning almost as if they don't notice them. Medicare faces insolvency by 2019. Social Security is projected to be spending more than it's collecting in taxes by 2017. Yet both Obama and McCain offer only minor fixes — and few specifics even about the modest ideas they do float. Bigger, bolder, more sweeping approaches are needed, and fast, say the experts. "They're not preparing the country for sacrifice," said Robert Bixby, the executive director of the Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan budget watchdog group. Click here to read the whole story.

New paper: Employment-Based Retirement Plan Participation: Geographic Differences and Trends, 2007

The Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) released a new paper by Craig Copeland examining pension plan participation across the country and trends over time. This paper closely examines the level of participation by workers in public- and private-sector employment-based pension or retirement plans, based on the U.S. Census Bureau's March 2008 Current Population Survey (CPS), the most recent data currently available. Among full-time, full-year wage and salary workers ages 21-64 (those with the strongest connection to the work force), just over 63 percent worked for an employer or union that sponsors a retirement plan, and 55 percent participated in a plan. The paper begins with an overview of retirement plan types and participation in these types of plans. Next, it describes the data used in this study, along with their relative strengths and weaknesses. From these data, results on participation in employment-based retirement plans are analyzed for 2007 across various worker characteristics and those of their employers. The paper then explores retirement plan participation across U.S. geographic regions, including a state-by-state comparison and a comparison of certain consolidated statistical areas (CSAs). In addition to the results for 2007, trends from 1987-2007 in employment-based retirement plan participation are presented across many of the same worker and employer characteristics as used for 2007. The paper concludes with a discussion of this study's findings. Click here to access the paper.

Friday, October 10, 2008

New polling data on Social Security personal accounts

PollingReport.com has the results of some new polling on public approval of adding personal accounts to social security. As of early October, according to a CNN poll, 36 percent of adults favored adding personal accounts while 62 percent were opposed. That doesn't surprise me very much, given what's happened in the markets over the past year. What did surprise me was the CNN finding from June of this year, which I had not previously seen. At that time, support was effectively evenly split, with 47 percent in favor and 48 percent opposed. Given that many on the left like to say that the public had soundly rejected the idea of accounts in 2005, the results from last June were surprising. That said, given the stock market crash and other issues such as transition costs, the chances of any form of "carve out" account financed from the existing payroll tax seem very small. The next fight may be over how to handle additional contributions to Social Security. Democrats will tend to want tax increases paid to the current program, while Republicans will likely favor the option putting any additional Social Security taxes into "add on" accounts. Once the markets have stabilized, that will be a very interesting contrast. CNN/Opinion Research Corporation Poll. Oct. 3-5, 2008. N=1,006 adults nationwide. MoE ± 3. "As you may know, a proposal has been made that would allow workers to invest part of their Social Security taxes in the stock market or in bonds, while the rest of those taxes would remain in the Social Security system. Do you favor or oppose this proposal?" . Favor Oppose Unsure % % % 10/3-5/08 36 62 2 6/26-29/08 47 48 4

Thursday, October 9, 2008

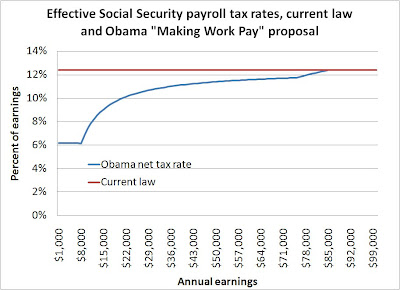

How Obama would change effective payroll tax rates and Social Security progressivity?

This hadn't gotten much discussion to date, but Sen. Obama has a component of his tax plan – called "Making Work Pay" – that would introduce significant progressivity into the tax side of Social Security. His plan is designed to partially or fully compensate workers for the employee share of the Social Security payroll tax – 6.2 percent of the 12.4 percent total tax. Workers would receive a refundable tax credit equal to 6.2% of wages up to $8,000, with a maximum credit of $500 per worker and $1,000 per couple. This is the source of the "tax cuts" Obama references for lower and middle income households. The Tax Policy Center assumes the credit phases out at 5 cents for each dollar of earnings above $75,000, meaning it declines to zero at $85,000. How does this change the effective Social Security payroll tax rate? The chart below shows the net payroll tax as a percentage of earnings for a single worker, with earnings levels from zero to $102,000 (the current cap on payroll taxes). The net tax rate is 6.2 percent of wages up to $8,000, gradually increasing to the statutory rate of 12.4 percent of wages by $85,000 and remaining constant up to the cap. How would this affect the progressivity of the Social Security program taken as a whole? Remember, while the Social Security payroll tax may be regressive – a fact those on the left often cite – Social Security benefits are progressive. So you need to look at both taxes and benefits together to understand the progressivity of both current law Social Security and the program net of Sen. Obama's new tax credit. Commonly Social Security progressivity is described through what is called the "money's worth ratio," which is the ratio of lifetime benefit received by a given individual to lifetime taxes paid. Both taxes and benefits are expressed in present value form, by discounting them at the government bond rate. To put things in terms of rates of return, a money's worth ratio of 1, in which lifetime benefits are equal to lifetime taxes, implies that the individual earned a rate of return on their payroll taxes equal to the return on government bonds. Social Security's actuaries periodically calculate money's worth ratios for stylized workers at different earnings levels. The data used here come from a 2007 publication and are for single earners retiring in 2008. The SSA actuaries use four stylized lifetime earnings levels. They are: Very low: Earns around 25 percent of the average wage, or around $10,500 per year. Around 20 percent of workers are in this group (meaning that this is the closest descriptor of their average earnings). Low: Earns around 45 percent of the average wage, or around $18,900 per year. Around 22 percent of workers are in this group. Medium: Earns around 100 percent of the average wage, or around $42,000 per year. Around 28 percent of workers are in this group. High: Earns around 160 percent of the average wage, or around $67,000 per year. Around 21 percent of workers are in this group. Maximum: Earns the maximum taxable wage each year, or around $102,000. Around 10 percent of workers are in this group. The following table compares the money's worth ratios for each worker type, assuming retirement at age 65 in 2008, to what they would have been under the Obama proposal. Net money's worth ratio Earnings level Current law Obama payroll tax rebate Very low 1.19 1.88 Low 0.87 1.1 Medium 0.64 0.71 High 0.53 0.56 Maximum 0.47 0.47 Assumes single male worker, retiring in 2008 at age 65

For instance, under current law a very low earner could expect to receive 1.19 times more in lifetime benefits than they pay in lifetime taxes. Since this comparisons are made to present values, discounted at the government bond rate of return (around 3 percent above inflation), this implies a rate of return on payroll taxes of around 4 percent above inflation. Under the Obama proposal, the net money's worth ratio for a very low earner would increase to around 1.88; total benefits would be the same, but lifetime taxes would be significantly lower. While comparisons are not straightforward, this implies an annual return on taxes of around 6.1 percent above inflation. Over a lifetime, the differences are significant.

The chart below uses the data above shows the "slant" of the Social Security program's progressivity under the Obama proposal. As can be seen visually, the system would be significantly more progressive than under current law. This may or may not be a good thing, according to your perspective, but it seems not to be something that should go undiscussed.

Now, what would the effect of the Obama plan be on Social Security's financing? After all, it effectively rebates part or all of the employee share of the Social Security payroll tax. The answer is that technically it would not affect Social Security's financing at all. These rebates, while based on the Social Security payroll tax, would be paid from general tax revenues – broadly speaking, income taxes. The total general revenue cost of the Obama proposal over 10 years is $728 billion, according to the Tax Policy Center.

That said, it's worth comparing the cost of Obama's proposal to those for personal retirement accounts, whose "transition costs" would also would be funded out of general revenue. The last detailed analysis of President Bush's personal accounts proposal I've seen was for the 2007 budget, which forecast a 10-year total cost of around $779 billion. In other words, the two policies cost around the same in the short term. Over the long-term, however, the Bush plan was designed to save those early contributions to help reduce Social Security costs. In other words, almost every dollar of costs in the near term was recouped in later years. The Obama plan, however, is simply an effective reduction in payroll taxes which would have increased costs over the long term.

Note that these numbers omit any reference to Sen. Obama's formal Social Security plan, which would also increase progressivity by imposing a surtax of 2 to 4 percent on all earnings above $250,000. Together, these policies would significantly alter Social Security's progressivity and – some might argue – shift it closer to a welfare-type program.

Read more!