Courtesy of the Fiscal Times…

Read more!Thursday, July 28, 2016

New paper: "Labor Force Dynamics in the Great Recession and Its Aftermath: Implications for Older Workers"

"Labor Force Dynamics in the Great Recession and Its Aftermath: Implications for Older Workers"

CRR WP 2016-1, July 2016

GARY BURTLESS, Brookings Institution, Boston College - Retirement Research Center

Email: GBURTLESS@BROOK.EDU

Unlike prime-age Americans, who have experienced declines in employment and labor force participation since the onset of the Great Recession, Americans past 60 have seen their employment and labor force participation rates increase. In order to understand the contrasting labor force developments among the old, on the one hand, and the prime-aged, on the other, this paper develops and analyzes a new data file containing information on monthly labor force changes of adults interviewed in the Current Population Survey (CPS). The paper documents notable differences among age groups with respect to the changes in labor force transition rates that have occurred over the past two decades. What is crucial for understanding the surprising strength of old-age labor force participation and employment are changes in labor force transition probabilities within and across age groups.

The paper identifies several shifts that help account for the increase in old-age employment and labor force participation:

- Like workers in all age groups, workers in older groups saw a surge in monthly transitions from employment to unemployment in the Great Recession.

- Unlike workers in prime-age and younger groups, however, older workers also saw a sizeable decline in exits to nonparticipation during and after the recession. While the surge in exits from employment to unemployment tended to reduce the employment rates of all age groups, the drop in employment exits to nonparticipation among the aged tended to hold up labor force participation rates and employment rates among the elderly compared with the nonelderly. Among the elderly, but not the nonelderly, the exit rate from employment into nonparticipation fell more than the exit rate from employment into unemployment increased.

- The Great Recession and slow recovery from that recession made it harder for the unemployed to transition into employment. Exit rates from unemployment into employment fell sharply in all age groups, old and young.

- In contrast to unemployed workers in younger age groups, the unemployed in the oldest age groups also saw a drop in their exits to nonparticipation. Compared with the nonaged, this tended to help maintain the labor force participation rates of the old.

- Flows from out-of-the-labor-force status into employment have declined for most age groups, but they have declined the least or have actually increased modestly among older nonparticipants.

Some of the favorable trends seen in older age groups are likely to be explained, in part, by the substantial improvement in older Americans’ educational attainment. Better educated older people tend to have lower monthly flows from employment into unemployment and nonparticipation, and they have higher monthly flows from nonparticipant status into employment compared with less educated workers.

The policy implications of the paper are:

- A serious recession inflicts severe and immediate harm on workers and potential workers in all age groups, in the form of layoffs and depressed prospects for finding work.

- Unlike younger age groups, however, workers in older groups have high rates of voluntary exit from employment and the workforce, even when labor markets are strong. Consequently, reduced rates of voluntary exit from employment and the labor force can have an outsize impact on their employment and participation rates.

- The aged, as a whole, can therefore experience rising employment and participation rates even as a minority of aged workers suffer severe harm as a result of permanent job loss at an unexpectedly early age and exceptional difficulty finding a new job.

- Between 2001 and 2015, the old-age employment and participation rates rose, apparently signaling that older workers did not suffer severe harm in the Great Recession.

- Analysis of the gross flow data suggests, however, that the apparent improvements were the combined result of continued declines in age-specific voluntary exit rates, mostly from the ranks of the employed, and worsening reemployment rates among the unemployed. The older workers who suffered involuntary layoffs were more numerous than before the Great Recession, and they found it much harder to get reemployed than laid off workers in years before 2008. The turnover data show that it has proved much harder for these workers to recover from the loss of their late-career job loss.

Wednesday, July 27, 2016

Provisions of the “Save Our Social Security Act”

Wisconsin Republican Rep. Reid Ribble recently introduced the “Save Our Social Security Act,” which combines tax increases and benefit reductions to restore Social Security to 75-year actuarial balance. The bipartisan bill has been co-sponsored by Reps. Dan Benishek (MI), Jim Cooper (TN), Cynthia Lummis (WY), Scott Rigell (VA) and Todd Rokita (IN).

More information is available at Rep. Ribble’s web page, but following are the main provisions of the bill and the percentage of the 75-year actuarial deficit that each provision would address.

Increase Contribution and Benefit Base (34%)

- Increase payroll subject to taxes over 5 years to 90%, then index to 90% (current cap is $118,500)

- FY2017: $156,550

- FY2018: $194,600

- FY2019: $232,650

- FY2020: $270,700

- FY2021: $308,750

- FY2022: shall be determined by the Commissioner – “such that the percentage of the total earnings for all workers that are taxable is equal to 90% for each calendar year.”

Modification of Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) formula (10%)

Changes to the formula factor used to calculate benefits of high earners from 15% to 5% over 5 years or 2% a year from 2017-2021.

- Adds an additional benefit of 2.5% of earnings over $9,875 (# is equal to current tax cap)

- Current PIA formula for an individual becoming eligible in 2016, will be the sum of:

- 90 % of the first $856 of average indexed monthly earnings (AIME), plus

- 32 % of AIME over $856 and through $5,158, plus

- 15 % of AIME over $5,157 up to $9,875 (# will change to current the tax cap)

Increase Full/Maximum Retirement Age, early retirement remains 62 (35%)

- Starting in 2022, full retirement age increases from age 67 to 69

- Phase-in of adding 2 months to retirement every year for 12 years (currently 1 month).

- After the phase-in is complete in 2034

- Increase the NRA 1 month every 2 years to keep up with life expectancy and the ratio of work/retirement, examined every 10 years in case of needed adjustments.

- Extension of maximum age for entitlement to delayed retirement credit to 72 (was 70)

Cost of Living Adjustments (19%)

- Move from current CPI-W to C-CPI-U

- CPI-U is a more general index and seeks to track retail prices as they affect all urban consumers.

- Encompasses about 87 % of the U.S. population.

- C-CPI-U accounts for how people switch their purchases as relative prices change

- CPI-W is a more specialized index and seeks to track retail prices as they affect urban hourly wage earners and clerical workers.

- Encompasses about 32% of the U.S. and is a subset of the CPI-U group

- Places a slightly higher weight on food, apparel, transportation, and other goods and services.

- It places a slightly lower weight on housing, medical care, and recreation.

- CPI-U is a more general index and seeks to track retail prices as they affect all urban consumers.

Create minimum benefit at 125% Poverty (-5%)

- Percentage of benefit is phased-in dependent upon number of eligible working years

Offer bump-up for very old beneficiaries (-6%)

- Increase benefit amount after 20 years of eligibility

Calculate benefit based on highest 38 years (13%)

- Changes a portion of how benefits are calculated to be based on highest 38 years of work instead of the current 35.

- Change is phased in

Protection of Social Security Trust Fund

- Provides a point of order against consideration of any spending or tax legislation that would cause Trust Fund totals to be less than needed for the covered fiscal year.

Tuesday, July 26, 2016

NBER Summer Institute Agenda and Papers (Aging)

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, INC.

SI 2016 Aging

David M. Cutler, and Jonathan S. Skinner, Organizers

July 25-29, 2016

PROGRAM

Nicole Maestas, Harvard University and NBER

Kathleen Mullen, RAND Corporation

David Powell, RAND Corporation

Till M. von Wachter, University of California at Los Angeles and NBER

Jeffrey B. Wenger, RAND Corporation

American Working Conditions

Daniel K. Fetter, Wellesley College and NBER

Lee Lockwood, Northwestern University and NBER

Government Old-Age Support and Labor Supply: Evidence from the Old Age Assistance Program

David M. Cutler, Harvard University and NBER

Wei Huang, Harvard University

Adriana Lleras-Muney, University of California at Los Angeles and NBER

Economic Conditions and Mortality: Evidence from 200 Years of Data

Ruixue Jia, University of California at San Diego

Hyejin Ku, University College London

The Price of the East Asian Miracle: Generational Cultural Shift and Elderly Suicide

Itzik Fadlon, University of California at San Diego and NBER

Torben Heien Nielsen, University of Copenhagen

Intra-Household Dependencies in Health and Health Behaviors

Gopi Shah Goda, Stanford University and NBER

Matthew Levy, London School of Economics

Colleen Flaherty Manchester, University of Minnesota

Aaron Sojourner, University of Minnesota

Joshua Tasoff

The Role of Time Preferences and Exponential-Growth Bias in Retirement Savings

Daniel J. Benjamin, University of Southern California and NBER

Mark Fontana

Miles S. Kimball, University of Michigan and NBER

Reconsidering Risk Aversion

Partha Bhattacharyya, National Institutes of Health

NIH Funding for Health Economics

Lorenz Kueng, Northwestern University and NBER

Evgeny Yakovlev, Acumen LLC

Long-Run Effects of Public Policies: Endogenous Alcohol Preferences and Life Expectancy in Russia

Sumit Agarwal, National University of Singapore

Jessica Pan, National University of Singapore

Wenlan Qian, National University of Singapore

Age of Decision: Pension Savings Withdrawal and Consumption and Debt Response

Paul Bingley, The Danish National Centre for Social Research

Alessandro Martinello, Lund University

The Effect of Schooling on Wealth Accumulation Approaching Retirement

Xi Chen, Yale University

Lipeng Hu, Peking University

Jody Sindelar, Yale University and NBER

Leaving Money on the Table? Social Pension Enrollment and Well-being of the Aging Population in China

Thomas DeLeire, Georgetown University and NBER

Andre Chappel, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Kenneth Finegold, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Emily Gee, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Do Individuals Respond to Cost-Sharing Subsidies in their Selections of Marketplace Health Insurance Plans?

Jonathan Gruber, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and NBER

Jason Abaluck, Yale University and NBER

Addressing Choice Inconsistencies in Choice of Health Insurance Plans

Pietro Tebaldi, Stanford University

Estimating Equilibrium in Health Insurance Exchanges: Price Competition and Subsidy Design Under the ACA

Amanda Starc, University of Pennsylvania and NBER

Robert Town, University of Pennsylvania and NBER

Internalizing Behavioral Externalities: Benefit Integration in Health Insurance

Leemore Dafny, Northwestern University and NBER

Kate Ho, Columbia University and NBER

Robin S. Lee, Harvard University and NBER

Price Effects of Cross-Market Combinations: Theory and Evidence from Hospital Markets

Nicolas R. Ziebarth, Cornell University

Stefan Pichler, ETH Zurich

The Pros and Cons of Sick Pay Schemes: Testing for Contagious Presenteeism and Shirking Behavior

Benjamin Friedrich, Yale University

Martin Hackmann, Pennsylvania State University

Parental Leave Programs, Nurse Shortages, and Patient Health

David W. Silver, University of California at Berkeley

Haste or Waste? Peer Pressure and the Distribution of Marginal Returns to Health Care

Diane E. Alexander, Princeton University

How do Doctors Respond to Incentives? Unintended Consequences of Paying Doctors to Reduce Costs

Zack Cooper, Yale University

Amanda E. Kowalski, Yale University and NBER

Eleanor N. Powell, University of Wisconsin-Madison

What Does a Hospital Do with Eighteen Million Dollars? Evidence From the Passage of Medicare Part D

Scott Barkowski, Clemson University

The Effect of Specialist Cost Information on Primary Care Physician Referral Patterns

NBER Summer Institute Agenda and Papers (Aging/Social Security)

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, INC.

SI 2016 Aging/Social Security

Jeffrey B. Liebman, Organizer

July 27, 2016

Royal Sonesta Hotel

PROGRAM

Silvia Garcia-Mandico, Erasmus University Rotterdam

Pilar Garcia-Gomez, Erasmus University Rotterdam

Anne Gielen, Erasmus University Rotterdam

Owen O'Donnell, University of Macedonia

Back to Work: Employment Effects of Tighter Disability Insurance Eligibility in the Netherlands

Dayanand S. Manoli, University of Texas at Austin and NBER

Andrea Weber, University of Mannheim

The Effects of the Early Retirement Age on Retirement Decisions

Alexander M. Gelber, University of California at Berkeley and NBER

Timothy J. Moore, George Washington University and NBER

Alexander Strand, Social Security Administration

The Effect of Disability Insurance Payments on Beneficiaries� Earnings

Marguerite Burns, University of Wisconsin

Laura Dague, Texas A&M University

The Effect of Expanding Medicaid Eligibility on Supplemental Security Income Program Participation

Xi Chen, Yale University

Does Money Relieve Depression? Evidence from Social Pension Eligibility

Xavier Gabaix, New York University and NBER

Behavioral Macroeconomics via Sparse Dynamic Programming

New paper: “How Can We Realize the Value That Annuities Offer in a 401(k) World?”

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College has released a new Issue in Brief:

“How Can We Realize the Value That Annuities Offer in a 401(k) World?”

by Steven A. Sass

The brief’s key findings are:

- A growing number of people are entering retirement with more 401(k) savings and less annuity income from Social Security and traditional pensions.

- Annuities assure a lifelong income stream and – compared to other draw-down options – can provide attractive payouts, which can help cover late-life health costs.

- But few individuals buy annuities, partly due to behavioral barriers such as the complexity of valuing the product and the way that draw-down options are framed.

- Options for overcoming these barriers include:

- educating individuals to focus more on the income they can draw from their nest egg, rather than its size; and

- automatically putting a portion of 401(k) assets in an annuity, perhaps an Advanced Life Deferred Annuity that kicks in later in retirement.

Friday, July 22, 2016

New paper: “Labor Force Dynamics in the Great Recession and its Aftermath: Implications for Older Workers”

July 2016

Labor Force Dynamics in the Great Recession and its Aftermath: Implications for Older Workers

by Gary Burtless

WP#2016-1 Abstract

Unlike prime-age Americans, who have experienced declines in employment and labor force participation since the onset of the Great Recession, Americans past 60 have seen their employment and labor force participation rates increase. In order to understand the contrasting labor force developments among the old, on the one hand, and the prime-aged, on the other, this paper develops and analyzes a new data file containing information on monthly labor force changes of adults interviewed in the Current Population Survey (CPS). The paper documents notable differences among age groups with respect to the changes in labor force transition rates that have occurred over the past two decades. What is crucial for understanding the surprising strength of old-age labor force participation and employment are changes in labor force transition probabilities within and across age groups.

The paper identifies several shifts that help account for the increase in old-age employment and labor force participation:

- Like workers in all age groups, workers in older groups saw a surge in monthly transitions from employment to unemployment in the Great Recession.

- Unlike workers in prime-age and younger groups, however, older workers also saw a sizeable decline in exits to nonparticipation during and after the recession. While the surge in exits from employment to unemployment tended to reduce the employment rates of all age groups, the drop in employment exits to nonparticipation among the aged tended to hold up labor force participation rates and employment rates among the elderly compared with the nonelderly. Among the elderly, but not the nonelderly, the exit rate from employment into nonparticipation fell more than the exit rate from employment into unemployment increased.

- The Great Recession and slow recovery from that recession made it harder for the unemployed to transition into employment. Exit rates from unemployment into employment fell sharply in all age groups, old and young.

- In contrast to unemployed workers in younger age groups, the unemployed in the oldest age groups also saw a drop in their exits to nonparticipation. Compared with the nonaged, this tended to help maintain the labor force participation rates of the old.

- Flows from out-of-the-labor-force status into employment have declined for most age groups, but they have declined the least or have actually increased modestly among older nonparticipants.

Some of the favorable trends seen in older age groups are likely to be explained, in part, by the substantial improvement in older Americans’ educational attainment. Better educated older people tend to have lower monthly flows from employment into unemployment and nonparticipation, and they have higher monthly flows from nonparticipant status into employment compared with less educated workers.

The policy implications of the paper are:

- A serious recession inflicts severe and immediate harm on workers and potential workers in all age groups, in the form of layoffs and depressed prospects for finding work.

- Unlike younger age groups, however, workers in older groups have high rates of voluntary exit from employment and the workforce, even when labor markets are strong. Consequently, reduced rates of voluntary exit from employment and the labor force can have an outsize impact on their employment and participation rates.

- The aged, as a whole, can therefore experience rising employment and participation rates even as a minority of aged workers suffer severe harm as a result of permanent job loss at an unexpectedly early age and exceptional difficulty finding a new job.

- Between 2001 and 2015, the old-age employment and participation rates rose, apparently signaling that older workers did not suffer severe harm in the Great Recession.

- Analysis of the gross flow data suggests, however, that the apparent improvements were the combined result of continued declines in age-specific voluntary exit rates, mostly from the ranks of the employed, and worsening reemployment rates among the unemployed. The older workers who suffered involuntary layoffs were more numerous than before the Great Recession, and they found it much harder to get reemployed than laid off workers in years before 2008. The turnover data show that it has proved much harder for these workers to recover from the loss of their late-career job loss.

DOWNLOAD FULL PAPER

Read more!New research on Australia’s pension system

"Means Testing of Public Pensions: The Case of Australia"

Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Paper No. 2016-338

GEORGE KUDRNA, University of New South Wales (UNSW)

Email: g.kudrna@unsw.edu.au

The Australian age pension is noncontributory, funded through general tax revenues and means tested against pensioners, private resources, including labour earnings. This paper constructs an overlapping generations (OLG) model of the Australian economy to examine the economy wide implications of several counterfactual experiments in the means testing of the age pension. These experiments include policy changes that both relax and tighten the existing mean test. We also consider a policy change that only exempts labour earnings from the means testing. Our simulation results indicate that tightening the existing means test combined with lower income tax rates leads to higher labour supply, domestic assets and consumption per capita, as well as to welfare gains in the long run, while labour earnings exemptions from the means testing have largely positive effects on labour supply at older ages. Population ageing is shown to further strengthen the case for the pension means testing.

"How Well Does the Australian Aged Pension Provide Social Insurance?"

Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Paper No. 2016-339

EMILY DABBS, Australian National University (ANU)

Email: emily.dabbs@uqconnect.edu.au

CAGRI S. KUMRU, Australian National University (ANU)

Email: cagri.kumru@anu.edu.au

Social security plays an essential role in an economy, but if designed incorrectly can distort the labor supply and savings behavior of individuals in the economy. We explore how well the Australian means-tested pension system provides social insurance by calculating possible welfare gains from changing the settings in the current means-tested pension system. This work has been explored by other researchers both in Australia and in other pension-providing economies. However, most research ignores the fact that welfare gains can be found by reducing the cost of the program. To exclude these welfare costs, this paper fixes the cost of the system. We find that the means-tested pension system is welfare reducing, but does provide a better outcome than an equivalent-costing PAYG system. We also find that if the benefit amount is held constant, and hence the cost of the pension program is allowed to vary, a taper rate of 1.0 is optimal. However, once we fix this cost, a universal benefit scheme provides the best welfare outcome.

Read more!Thursday, July 21, 2016

How Much Do Americans REALLY Need to Save for Retirement

There’s a big debate about how well Americans are saving for retirement. The major source of that debate is disagreement on how much a person ideally should save – some people claim you should have retirement savings equal to 8 times your final salary; others say 12; still others say 20. But what does this mean?

Over at Forbes I’ve tried to shed some light on this by including an interactive online calculator that lets the user analyze retirement saving needs for Americans of different income levels. You decide what kind of replacement rate different retirees need and the calculator figures out how much they need to save. The results may surprise you.

You can check out the article and calculator here.

Read more!Monday, July 18, 2016

Upcoming Event: Recent Trends in Mortality and the Impact on Entitlements with Stephen Goss

Savings and Retirement Foundation

Lunch Forum

Discussing

Recent Trends in Mortality and the Impact on Entitlements

with Stephen Goss

Wednesday, July 20

Noon to 1:00pm

Cato Institute

1000 Massachusetts Ave NW

Washington, DC 20001

Lunch will be provided.

This is a widely attended event.

Steve Goss has been Chief Actuary at the Social Security Administration since 2001. Mr. Goss joined the Office of the Chief Actuary in 1973 after graduating from the University of Virginia with a MA in Mathematics. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1971 with a BA, majoring in mathematics and economics. Mr. Goss is a member of the Society of Actuaries, the American Academy of Actuaries, the National Academy of Social Insurance, the Social Insurance Committee of the American Academy of Actuaries, and the Social Security Retirement and Disability Income Committee of the Society of Actuaries.

New paper: “Disability Benefit Generosity and Labor Force Withdrawal”

Disability Benefit Generosity and Labor Force Withdrawal

Kathleen Mullen, Stefan Staubli

NBER Working Paper No. 22419

Issued in July 2016

NBER Program(s): AG HE LS PE

A key component for estimating the optimal size and structure of disability insurance (DI) programs is the elasticity of DI claiming with respect to benefit generosity. Yet, in many countries, including the United States, all workers face identical benefit schedules, which are a function of one’s labor market history, making it difficult to separate the effect of the benefit level from the effect of unobserved preferences for work on individuals’ claiming decisions. To circumvent this problem, we exploit exogenous variation in DI benefits in Austria arising from several reforms to its DI and old age pension system in the 1990s and 2000s. We use comprehensive administrative social security records data on the universe of Austrian workers to compute benefit levels under six different regimes, allowing us to identify and precisely estimate the elasticity of DI claiming with respect to benefit generosity. We find that, over this time period, a one percent increase in potential DI benefits was associated with a 1.2 percent increase in DI claiming.

Available here.

Read more!New paper: “The Distributional Effects of Means Testing Social Security: Income Versus Wealth”

Distributional Effects of Means Testing Social Security: Income Versus Wealth

Alan Gustman, Thomas Steinmeier, Nahid Tabatabai

NBER Working Paper No. 22424

Issued in July 2016

NBER Program(s): AG LS PE

This paper compares Social Security means tests that would reduce benefits for recipients who fall in the top quarter of the income distribution with means tests aimed at those in the top quarter of the wealth distribution. Both means tests would reduce the average benefits for the affected groups by about $5,000. The analysis is based on data from the Health and Retirement Study and covers individuals aged 69 to 79 in 2010.

About 14.5 percent of retirees in this age group are both in the top quarter of income recipients and in the top quarter of wealth holders. Another 10.5 percent are top quarter income recipients, but not top quarter wealth holders; with an additional 10.5 percent top quarter wealth holders, but not top quarter income recipients.

We find that a means test of Social Security based on income has substantially different distributional effects from a means test based on wealth. Moreover, there are substantial differences when a Social Security means test based on income is evaluated in terms of its effects on individuals arrayed by their wealth rather than their income. Similarly, a means test based on wealth will be evaluated quite differently by policy makers who believe that income is the appropriate basis for a means test than by those who believe that means tests should be based on wealth.

Available here.

Read more!Blahous: Why a Social Security Fix Can’t Wait

Over at e21, Social Security Trustee and Mercatus Center fellow Chuck Blahous writes about the need for – as the Social Security Trustees often put it – prompt action on Social Security reform:

…financing corrections postponed from today until the early 2030s would need to take effect virtually immediately and be several times as painful, rendering enactment highly implausible. It would be far likelier then that legislators would resort to subsidizing Social Security from the government’s general fund. This would end longstanding arrangements through which Social Security has enjoyed unique popular support because it is perceived as a separate, self-financing program of benefits workers have earned with their payroll taxes.

Click here to read the whole article.

Friday, July 15, 2016

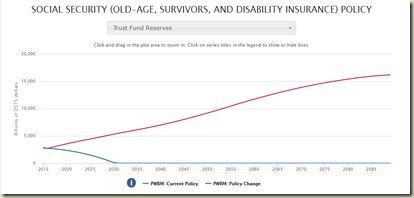

Check out the Penn Wharton Social Security Model

The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania has released a new Social Security simulation model that allows users to build their own reform plan. What’s interesting about the simulator is that it’s built on an independent microsimulation model of Social Security’s finances rather than pre-run reforms chosen by SSA’s actuaries. This means that as the model is further developed, additional reform options may become available, as well as outputs on the distribution of Social Security benefits. Well worth checking out.

You can find the model here.

Read more!Testimony from July 13 Senate Budget Committee Hearing on Retirement Security

Restoring the Trust for Americans At or Near Retirement

Date: Wednesday, July 13, 2016

Time: 9:30 a.m.

Location: 210 Cannon

Chairman Price Opening Statement

Witnesses:

Jason J. Fichtner, Ph.D.

Senior Research Fellow

Mercatus Center at George Mason University

Testimony | Truth in Testimony

Daniel C. Weber

Founder

Association of Mature American Citizens

Testimony | Truth in Testimony

Scott Gottlieb, M.D.

Resident Fellow

American Enterprise Institute

Testimony | Truth in Testimony

Monique Morrissey, Ph.D.

Economist

Economic Policy Institute

Testimony | Truth in Testimony

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

Coming Up! Retirement Policy in the New Economy

Coming up tomorrow! I'll be speaking at this event and promise a stimulating discussion.

Retirement Policy in the New Economy

- Congressman Joe Crowley New York’s 14th District Vice Chair of the Democratic Caucus

- Jonnelle Marte Moderator, The Washington Post

- Diane Oakley National Institute on Retirement Security

- Andrew Biggs American Enterprise Institute

- Alane Dent American Council of Life Insurers

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

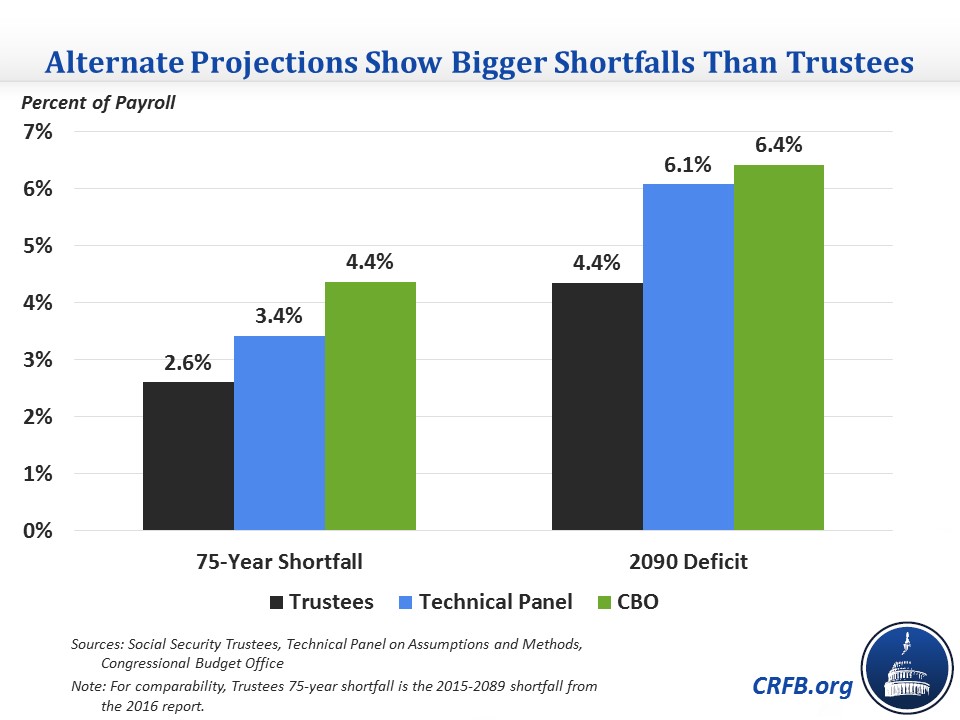

Is Social Security in Even Worse Shape Than We Thought?

Possibly. While the Social Security Trustees’ projections for Social Security’s finances get the most media attention, there are two other sets of projections – from the Congressional Budget Office and the Social Security Advisory Board’s Technical Panel on Assumptions and Methods. And both find a larger long-term deficit than do Social Security’s Trustees.

Click here to read the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s blog post on the subject. Worth reading.

Tuesday, July 5, 2016

Upcoming Event: Retirement Policy in the New Economy, Hosted by Third Way. July 13.

Getting to a comfortable retirement is a vastly different challenge for workers in the new economy than for those a generation ago. Workers today change jobs more frequently, are self-employed at higher rates, and are in charge of their own retirement savings to a far greater degree. For some workers in this economy, retirement security is stronger than ever. Yet many others who want to save for retirement through their job are unable to do so. Please join us for a range of perspectives and ideas as we discuss:

What is the extent of the retirement savings gap in America?

How can public policy expand participation in workplace retirement plans?

Congressman Joe Crowley

New York’s 14th District Vice Chair of the Democratic Caucus

Jonnelle Marte

Moderator, The Washington Post

Diane Oakley

National Institute on Retirement Security

Andrew Biggs

American Enterprise Institute

Alane Dent

American Council of Life Insurers

This event has been organized to meet the requirements for a widely attended event as set forth in the Congressional ethics rules. If you have any questions, please email mcoglianese@thirdway.org.

Read more!