"The Future of Old Age Income Security"

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research Paper No. 13-20

MUKUL G. ASHER, National University of Singapore - Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

Email: sppasher@nus.edu.sg

This is the revised version of the Robert Butler Memorial Lecture delivered at the International Centre Global Alliance Symposium on ‘The Future of Ageing’ on 21 June 2013 in Singapore. The lecture covers and discusses about the future of income security and social welfare discussing global trends in developed and developing countries using the 2012 Revision of the UNDESA’s World Population Prospects.

"Can Pensions Be Restructured in (Detroit’s) Municipal Bankruptcy?"

The Federalist Society, White Paper Series, October 2013

U of Penn, Inst for Law & Econ Research Paper No. 13-33

DAVID A. SKEEL, New York University School of Law, University of Pennsylvania Law School, European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI)

Email: dskeel@law.upenn.edu

This paper, which was written as a White Paper for the Federalist Society, describes and assesses the question whether public employee pensions can be restructured in bankruptcy, with a particular focus on Detroit. Part I gives a brief overview both of the treatment of pensions under state law, and of the Michigan law governing the Detroit pensions. Part II explains the legal argument for restructuring an underfunded pension in bankruptcy. Part III considers the major federal constitutional objections to restructuring. Part IV discusses arguments based on the Michigan Constitution and Part V assesses several Chapter 9 arguments against restructuring. None of these arguments appear to prevent restructuring. Assuming that pensions can in fact be restructured, Part VI discusses the Chapter 9 factors that may affect the extent to which they are or can be restructured in a particular case.

"The Cost of 'Choice' in a Voluntary Pension System"

2013 New York University Review of Employee Benefits and Executive Compensation 6-1 to 6-55

JONATHAN BARRY FORMAN, University of Oklahoma College of Law

Email: JFORMAN@OU.EDU

GEORGE A. (SANDY) MACKENZIE, Independent

Email: sandymackenzie50@gmail.com

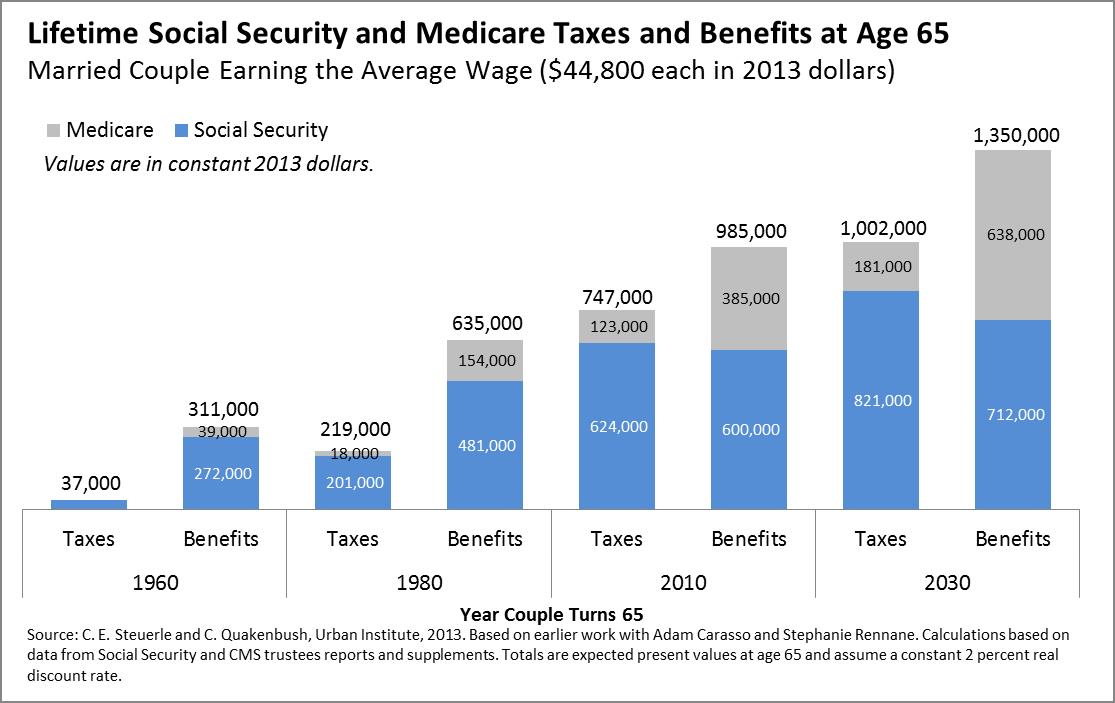

The United States and most other industrialized nations have multi-pillar retirement systems that fit within the World Bank’s multi-pillar model for retirement savings consisting of a first-tier public system, a second-tier employment-based pension system, and a third-tier of supplemental voluntary savings. While in many countries, the second-tier occupational pension is mandatory or quasi-mandatory, in the United States, both the second and third-tier retirement savings systems are voluntary. That is, employers are not required to offer pensions, and when they do, they have considerable choice over the type of pension plan to have and over many of that plan’s features. Moreover, when employers do offer a pension plan, it is probably a 401(k)-type plan that offers employees considerable choice about whether to participate, about how much to contribute, about how to invest those contributions (and prior accumulations), and about the timing and nature of distributions. In short, unlike our first-tier, mandatory Social Security system, America’s second-tier, private pension system is replete with choice: choices about the type of pension plan, choices about the amount and timing of contributions, choices about investments, and choices about the timing and nature of distributions.

To be sure, the availability of pension choices may be of value to employers and individuals, but, on the whole, the costs of choice almost certainly exceed the benefits. Pertinent here, one of the major problems with the current pension system is its incredible complexity. That complexity imposes significant costs on individuals, employers, and government, especially when compared to the relatively rigid, but straightforward, Social Security system. As more fully discussed below, the administrative costs for Social Security’s retirement system are well under 1% of benefits paid. Meanwhile, other than the cost for a payroll withholding service, employers incur almost no costs because of Social Security; and almost the only choice that workers face is the choice about when to take their benefits, at which point in time, a costless and simple application leads to a lifetime of inflation-adjusted retirement income.

On the other hand, employers, individuals, and government all incur significant costs in connection with the current pension system. Employers incur significant costs in choosing, designing, administering, or even outsourcing their pensions; individuals incur significant costs in connection with the management, investment, and distribution of their contributions and benefits; and the government incurs significant costs in regulating thousands of disparate pension plans and millions of Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). Also, because of the voluntary nature of our second-tier, private pension system, coverage and participation rates are low, and retirement savings may be inadequate for many retirees.

All in all, this Article focuses on the costs of choice in America’s voluntary private pension system. At the outset, Part II of this Article provides an overview of the current U.S. retirement system — both Social Security and private pensions. Next, Part III of this Article looks at the costs associated with the current Social Security and private pension systems. Finally, Part IV of this Article outlines some ways to reduce the costs associated with the private pension system. In particular, Part IV discusses how to reduce costs by moving to a universal, second-tier pension system; and Part IV also discusses some more modest approaches for reducing the costs associated with the current private pension system.

"Pensions, Employment, and Family Programs"

Well-Being and Social Policy 9 (1): 23-43, 2013

MARTHA MIRANDA-MUÑOZ, Interamerican Conference for Social Security (CISS)

Email: m.miranda@ciss.org.mx

NELLY AGUILERA, Interamerican Conference for Social Security (CISS)

Email: nelly_aguilera_aburto@hotmail.com

GABRIEL MARTINEZ, Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM)

Email: gabriel0317@gmail.com

Pension, employment, family, and health insurance programs constitute the four major categories of social policy. This report discusses the options for the design of programs within the first three categories based on a framework that aims at providing universal social security protection throughout Mexico. Although the core benefits of these programs are monetary benefits, their provision requires application of solid strategies specific to each program for the regulation of suppliers, provision of a fiscal framework, and interaction with other programs and institutions. Employment programs require use of a seamless design within the educational system and business training programs, as well as the adoption of an unemployment insurance program. Family programs, including the main programs that combat extreme poverty, should be incorporated into a general framework to allow them to serve as vehicles for the integration of the beneficiaries into society. At the same time, implementation of family programs is key to solving the special challenges of female workers, integrating the disabled into the labor market, adopting a policy for the comprehensive development of young children, and addressing the growing problem of long-term disability care. Finally, realization of successful pension programs requires a platform upon which to articulate the fiscal aspects, service solutions, and multiplicity of the increasing number of programs that serve the elderly and disabled.

"Race, Trust, and Retirement Decisions"

TERRANCE KIERON MARTIN, University of Texas - Pan American - College of Business Administration - Department of Economics & Finance, Texas Tech University

Email: martintk@utpa.edu

Using the 2008 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, this study investigates whether racial differences in trust can explain decisions to consult a financial planner and the variation in accumulated retirement wealth. Black and Hispanics are more likely to report having low trust compared to non-Black, non-Hispanic respondents. The results show evidence that low trust impacts the two outcome decisions of Blacks more relative to non-Black, non-Hispanic respondents. Low trust minimally affects Hispanics relative to non-Black, non-Hispanic respondents as it related to the decision to consult a financial planner and the accumulation of retirement wealth. Marginal effects of Tobit regression analysis show no evidence of racial difference in the effect of a financial planner.

"Non-Contributory Pensions"

SEBASTIAN GALIANI, University of Maryland

Email: galiani@econ.umd.edu

PAUL J. GERTLER, University of California, Berkeley - Haas School of Business, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)

Email: GERTLER@HAAS.BERKELEY.EDU

ROSANGELA BANDO, Inter-American Development Bank

Email: Rosangelab@iadb.org

The creation of non-contributory pension schemes is becoming increasingly common as countries struggle to reduce poverty. Drawing on data from Mexico’s Adultos Mayores Program (Older Adults Program) -- a cash transfer scheme aimed at rural adults over 70 years of age -- we evaluate the effects of this program on the well-being of the beneficiary population. Exploiting a quasi-experimental design whereby the program relies on exogenous geographical and age cutoffs to identify its target group, we find that the mental health of elderly adults in the program is significantly improved, as their score on the Geriatric Depression Scale decreases by 12%. We also find that the proportion of treated individuals doing paid work is reduced by 20%, with most of these people switching from their former activities to work in family businesses; treated households show higher levels of consumption expenditures (on average, an increase of 23%). Very importantly, we also rule out significant anticipation effects that might have been associated with the program transfers. Thus, overall, we find that non-contributory pension schemes target to the poor in developing countries can improve the well-being of poor older adults without having any indirect impact (through potential anticipation effects) on the earnings or savings of future program participants.

Read more!